Term limits don’t work.

The alternative, defeat by the voters, doesn’t work that well, either.

In either case, elected officials hold offices for long terms. They have better name recognition than their challengers, usually can raise more money and know how to use incumbency to their benefit.

Familiarity with office-holders can give voters confidence that they know what their backing will produce. Challengers must embody some risk because how they will perform remains to be seen.

In Maine, term limits apply to state offices – governor, legislators and constitutional officials like the attorney general or secretary of state. The general rule is eight years and out.

But an eight-year ticket to office also seems likely – if the incumbent wants to keep the seat.

Since the advent of the four-year term of governor in 1957, no incumbent who sought re-election has been defeated. One governor (James Longley) did not seek re-election in 1978 and another (Clinton Clawson) died in office in December 1959 after serving less than a year.

The original purpose of legislative term limits was to end some almost endless tenures. The prime target for some legislators was John Martin, the Aroostook County Democrat who was first elected in 1964 and is the longest-serving legislator in state history.

The problem with Maine term limits is they only ban consecutive terms in a single office. Martin, for example, has served three separate periods in the House, breaking the string with eight years in the Senate. Other legislators skip a term and start a new eight-year run.

The same system appears to attract former Gov. Paul LePage. He served two four-year terms, left office and now talks about running again in 2022.

The state term-limit system is weak, but there is no federal system. States cannot impose term limits on federal offices, which possibly would require a constitutional amendment.

In 1994, House Speaker Tom Foley (D-Washington) successfully challenged in court his state’s attempt to term-limit federal officials. Republican George Nethercutt, who supported term limits, promised to serve only three terms and upset Foley.

Holding office proved seductive for Nethercutt. He served five terms. But when he left the House to run for the Senate, his broken promise helped defeat him.

Since Margaret Chase Smith was a Maine senator, the state has sent eight people to the U.S. Senate. Smith was defeated by Democrat Bill Hathaway in 1972 when she tried for her fifth term; Hathaway then lost after a single term. Four Senators retired. Two, Republican Susan Collins and Independent Angus King, now serve.

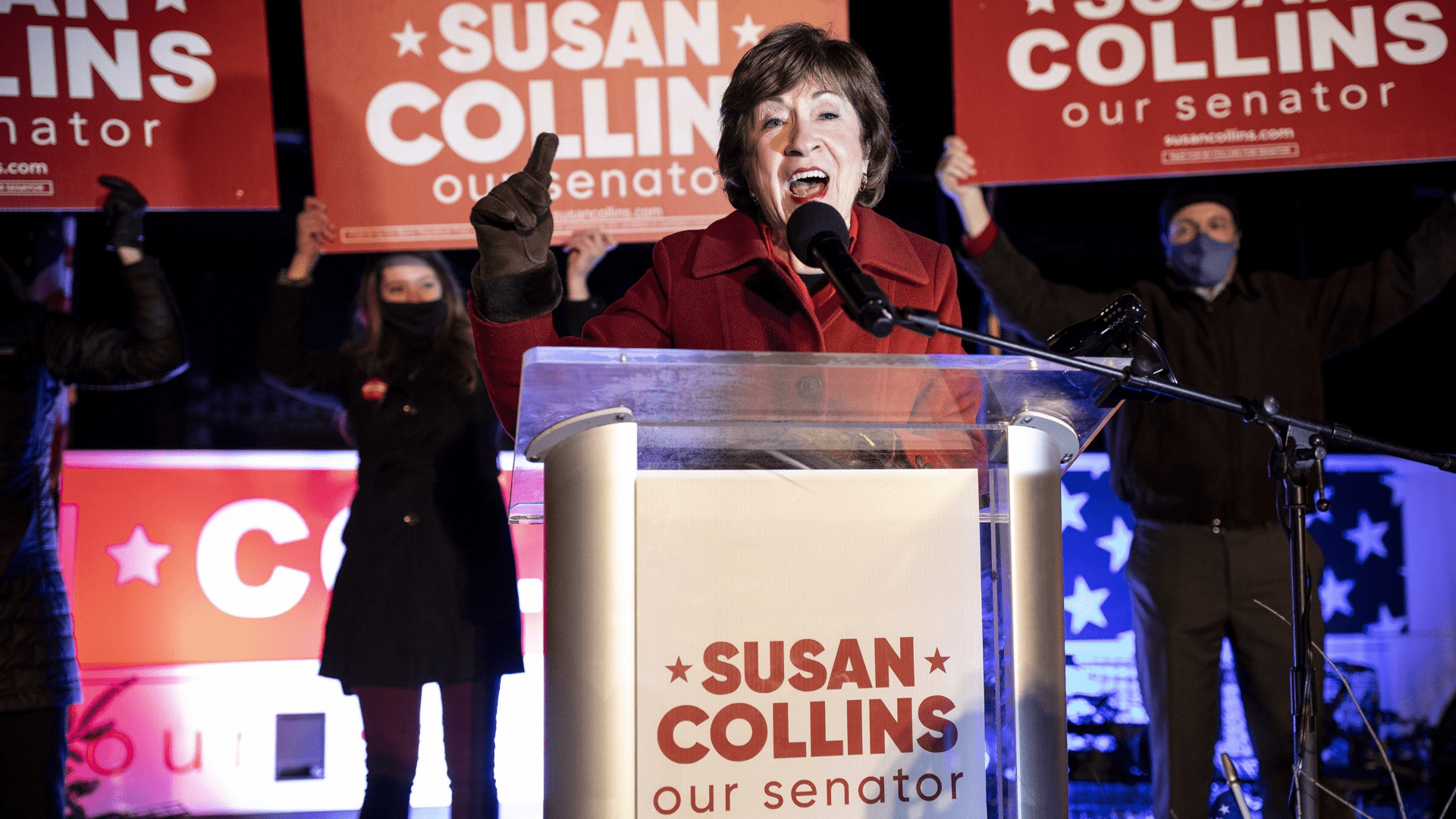

In 1996, when Collins first ran for the Senate, she said she wanted to serve two terms. She is now running for her fifth – as did Smith, her role model.

Traditionally, Republicans have favored term limits and Democrats have opposed them. Once in power, Democrats have held onto legislative control at the federal level and in many states longer than the GOP. That could explain the partisan split on term limits, though the difference in tenure seems to be fading.

Democrats maintain that voters should decide on terms. Republicans counter that, in practice, incumbents win. In the end, as Smith discovered, there may be another rule. As voters become familiar with their public officials, they may become more critical.

Obviously, Collins does not share her party’s traditional attitude. By staying in office, she gains seniority and more influential committee appointments. Also, she uses her reputation as a moderate to gain leverage. She has been reported as saying, “I have a lot of power – I like that.”

One reason for term limits is to keep public officials closer to the public. Politicians are less likely to keep apart from constituents when they know they must have a career outside of public office. This realization may keep them better attuned to popular sentiment.

One criticism of Collins is she doesn’t have much unstructured contact with Maine people. That may be a result of a long public life and relatively little of the life most of her constituents lead.

Conversely, long-term incumbents argue they can use their seniority to bring federal money home. And they gain independent expertise to develop their positions without overly relying on professional staff. Still, continually running for re-election means spending time on fundraising, not governing.

The question of term limits should be seen in a broad political context. If public sentiment determines it’s time for a change, that view can sweep all other considerations aside, including term limits.