About six years ago, my then boyfriend (now husband) and I moved into a lovely little house a few minutes outside of downtown Bar Harbor. It was set midway on a hill, about half a mile from the ocean, with enough space for a garden and some grape vines, and a mortgage rate that, in this market, feels like it may have been a mirage.

The house, which had been hastily constructed after the fire of 1947 (with help, unbeknownst to us at the time, from my great-grandfather), was 141 feet above sea level. It wasn’t in a flood zone. The entire town of Bar Harbor — shops, restaurants, movie theaters — lay downhill.

Yet when we called insurance companies, the big names told us they wouldn’t insure the property, because they were concerned about flood risk and rising seas. We politely explained that if the house were ever to be underwater, the entire town of Bar Harbor would have to first disappear under the waves.

They wouldn’t budge. Eventually we found coverage through a local company whose agents knew the landscape and the flood risk.

I had forgotten all of this until recently, when I read this excellent piece in The Quoddy Tides a few weeks back, about property insurance in Washington County. Big-name companies, it turns out, are now dropping entire zip codes (including Lubec) from their portfolios over concerns about wind and waves.

“Winds are a huge factor,” property owner James Pollowitz, who is in the midst of a major renovation on an historic home in downtown Eastport, told the paper. “They’re getting huge numbers of claims on houses [around the country] that probably shouldn’t have been built where they are.”

Like us, Pollowitz eventually found a local company that knew the area to insure the home. But finding property insurance is becoming more and more challenging, as Paul McKee, president of the Maine Association of Realtors, told the Tides, even in areas that aren’t close to flood zones.

In a piece for The Monitor last August, Marina Schauffler pointed out that insurance companies used to moderate their risks by diversifying.

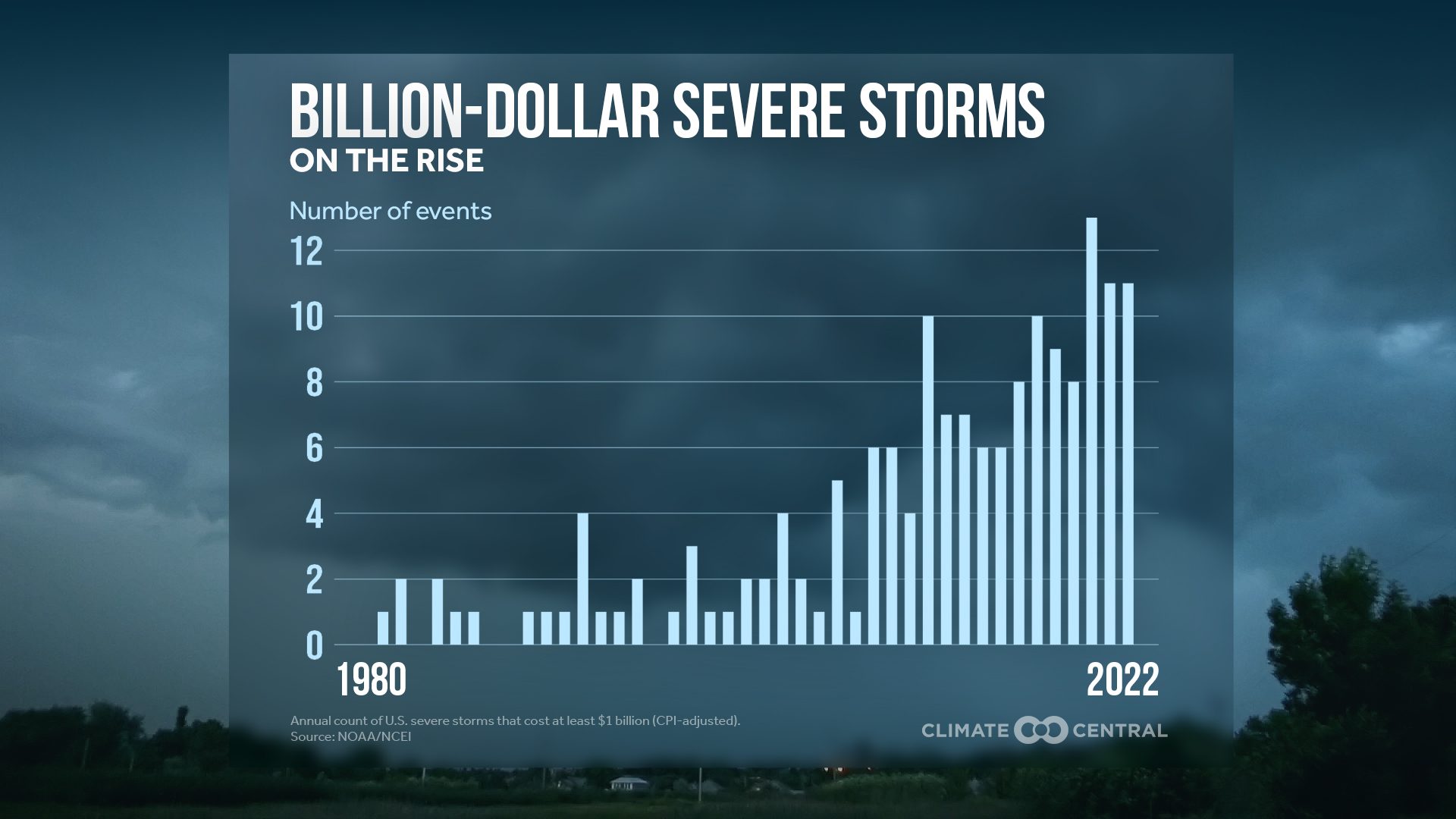

That’s becoming harder and harder to do, as severe storms — like the ones we saw in January and March — are on the rise, and reinsurance costs (what insurance companies pay to insure themselves) are also going up. (Will we one day have insurance for the reinsurance for the insurance? Only time will tell.)

Those costs are getting passed on to homeowners. Home insurance policy premiums rose an average of 21 percent between May 2022 and 2023, according to a report by Policygenius, which analyzes industry trends.

That increase is due in large part to insurance companies paying out for disasters, many of which are related to climate change: in 2022, U.S. insurers paid out $99 billion in claims due to natural disasters, a figure that’s rising every year.

Some states, most notably Florida, have responded to company pullouts by creating their own pooled insurance programs, like Fair Access to Insurance Requirements (FAIR), which is now Florida’s largest insurer, with more than a million policies. Maine has yet to create such a program, although it could under statute.

“People can deny climate change because it’s all far away, elsewhere, in the future,” Charles Colgan, a former Maine state economist who directs research at the Center for the Blue Economy in Monterey, California, told The Monitor last year. “But when the insurance company cancels your policy and you can’t sell your house, that’s when things get real.”