This reporting was supported by the International Women’s Media Foundation’s Howard G. Buffett Fund for Women Journalists.

This is part of a continuing series.

Bobby Nightingale’s future hinges on his defense attorney convincing a jury that he’s not a murderer. He fears now that some of the words used against him at trial could be his own.

State police listened in on parts of at least two of the dozens of calls Nightingale made from the Aroostook and Cumberland county jails to his attorney as they discussed his alibi, witnesses and defense strategies for two homicides he says he did not commit.

“They’re supposed to play by rules and I feel like they cheated,” said Nightingale, who has been behind bars, and awaiting trial, since 2019.

Jaquille Coleman also had portions of his attorney calls listened to by state police while in the Androscoggin County Jail on charges that he shot and killed an ex-girlfriend.

State police also listened to some of a strategy call between Abdikadir Nur and his attorney, who was trying to get murder charges against Nur dropped after DNA evidence didn’t match his.

If convicted, their crimes each carry a sentence of 25 years to life in prison. None of these men have had their day in court, and their defense attorneys worry now that they won’t get a fair trial.

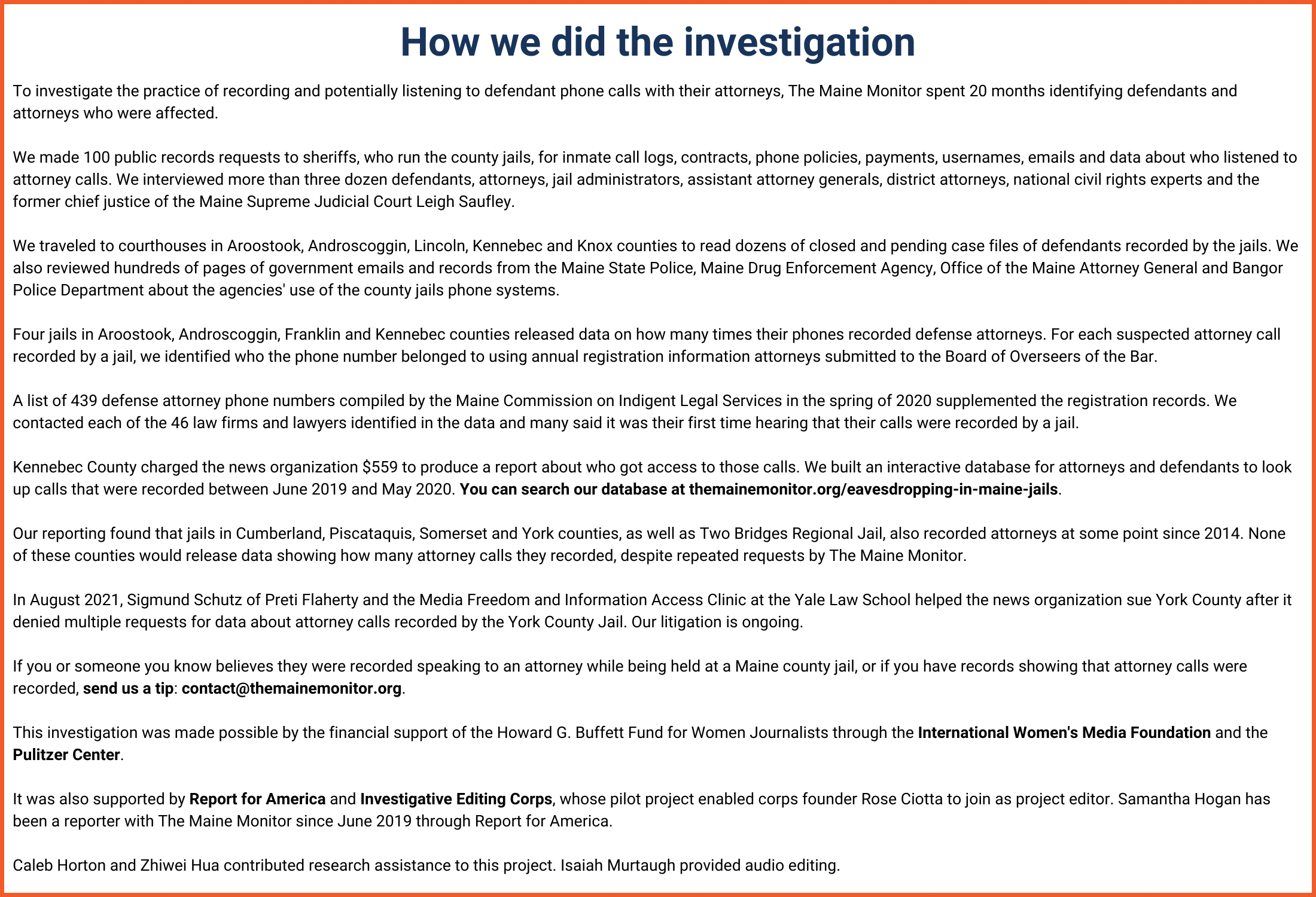

Jailed defendants across Maine were deceived by jail officials who promised they could make private phone calls to their attorneys, a months-long investigation by The Maine Monitor has found. Jails routinely and secretly recorded attorney-client calls. And some recorded calls were listened to by law enforcement as they investigated cases.

In one county, authorities recorded hundreds of attorney-client calls in a year. Rarely were attorneys and defendants told of the eavesdropping, leaving them wondering whether authorities gleaned information that helped them prosecute their cases.

Equipped with phone systems from two of the nation’s largest prison telecom companies, the jails’ recording of attorney calls has become endemic across the state, The Maine Monitor has found. All in spite of a state law and federal constitutional rights that make the practice illegal.

The state’s history of eavesdropping on attorneys was pieced together by The Maine Monitor through interviews with three dozen attorneys, defendants, sheriffs and legal experts, hundreds of pages of court records and government emails, data and 100 public records requests.

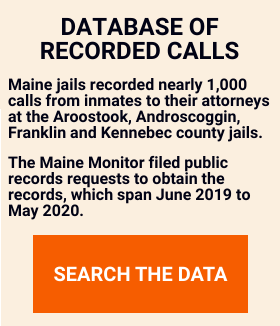

So far, the news organization has identified nearly 1,000 attorney calls that were recorded by Androscoggin, Aroostook, Franklin and Kennebec county jails between June 2019 and May 2020 — affecting nearly 200 defendants and 46 law firms, data show. Court records in other counties show the monitoring dates to at least 2014.

The county sheriffs, who have the power to stop the recordings at the state’s 15 jails, have instead done little, according to interviews and records. Most have refused to release data that would show how widespread the practice is statewide and The Maine Monitor is suing one of the counties to obtain the documents.

The confidentiality of attorney-client conversations is one of the most “sacred privileges,” state Rep. Thom Harnett (D-Gardiner), a retired career prosecutor with the attorney general’s office, told The Maine Monitor.

“If a prosecutor has been provided — even if they didn’t request it — with detailed defense strategy, that’s a real problem,” Harnett said. “These are fundamental constitutional rights that we’re talking about, and with those rights come the responsibility of government to make sure that this process is functioning properly. And what you’re describing is not proper.”

In some cases, defendants were sentenced to prison with no consideration that this right had been violated. The practice has become so routine that law enforcement and prosecutors who listened in on calls remain assigned to the cases, The Maine Monitor’s investigation found.

Jails nationwide routinely record inmate phone calls. Officials say the surveillance is part of their responsibility to enforce security, stem the flow of contraband and prevent the harassment of victims. Prosecutors and investigators eavesdrop on calls for information that will help their cases, but attorney calls are not supposed to be shared with them.

The law hasn’t caught up with the facts. I don’t think anyone contemplated that there could be endemic levels of listening to phone calls.”

— John Tebbetts, defense attorney

Attorney-client privilege is a cornerstone of the American legal system. It means people accused of crimes have a constitutional right to fully and freely seek legal advice from a lawyer, including by phone, said Corene Kendrick, the deputy director of the ACLU National Prison Project.

“The 6th Amendment was written before telephones existed so obviously it doesn’t explicitly say, ‘You have a right to confidential phone calls,’ but it’s pretty clear across the country in federal courts and in the Supreme Court that the 6th Amendment does protect attorney-client communications when the client is incarcerated,” Kendrick said.

The risk of attorney conversations being monitored by a Maine county jail is so serious that multiple defense attorneys said they are now delaying critical conversations until they are with clients in-person — sometimes waiting until they are seated in a courtroom to speak. They routinely tell their clients not to talk about their cases on the jails’ phones.

Prosecutors too can face problems when attorney calls are listened to, since it can give the defense grounds to try to get charges dismissed, although experts say the bar is very high for them to succeed.

Repeated warnings

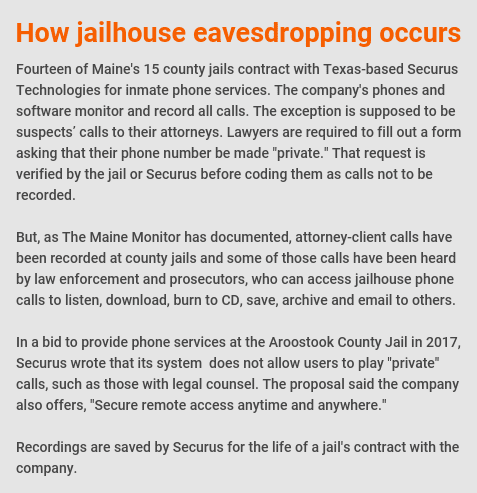

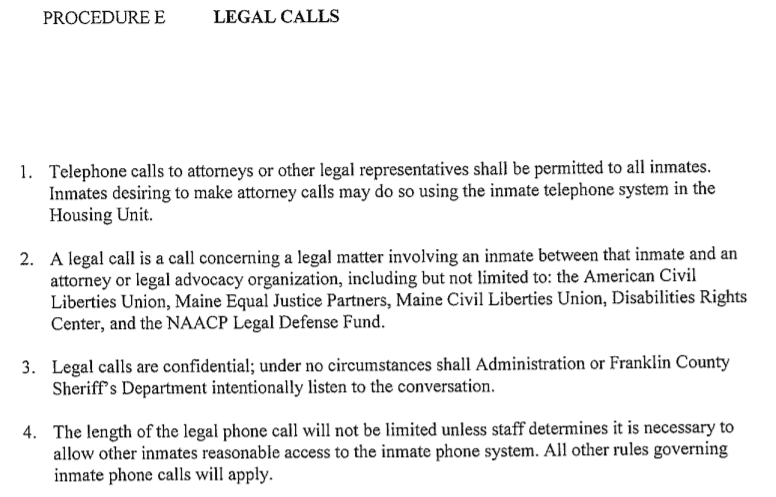

In Maine, 14 of the 15 jails contract with Securus Technologies to monitor inmate phone calls. The company, in bids to install its systems at jails, says that anyone with access to its phone system can listen to live and recorded conversations. The jails are supposed to make attorney phone numbers private so their calls cannot be listened to or recorded.

The Texas-based company has paid to settle lawsuits in California, Texas and Kansas for recording attorney-client conversations. Securus Technologies and a private prison agreed to a $3.7 million settlement in 2020 for recording attorney calls and meetings and sharing those conversations with a federal prosecutor, according to court records. In each instance, Securus denied intentionally recording attorney calls and challenged whether the calls were private.

That attorney calls were being recorded in Maine first surfaced in the spring of 2020. Top state prosecutors were initially dismissive that attorneys were being recorded on a large scale by the jails despite repeated warnings. Yet, The Maine Monitor found that attorney calls were recorded through August 2021.

The state’s attorney general office got at least four warnings that attorney calls were being recorded and shared but took little action to stop the practice, The Maine Monitor found.

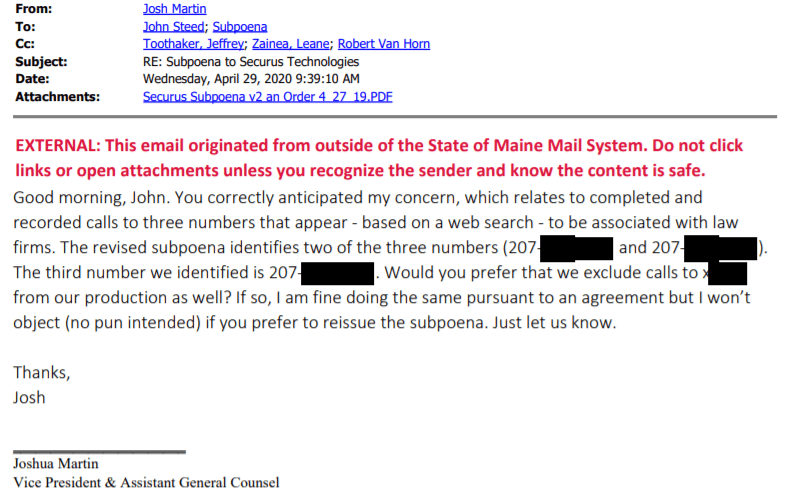

One of the warnings came early in the spring of 2020. A Securus employee refused to release calls that a state’s key witness, in a murder case, made to her attorney from jail in April 2020. A judge blocked anyone from accessing those calls, records and interviews show.

In June 2020, District Attorney Andrew Robinson wrote to Deputy Attorney General Lisa Marchese that he was concerned that sheriffs were unaware of a state law that said they were not allowed to interfere with attorney calls. It became public soon after that two jails in his district had recorded 215 attorney calls during the prior year.

By then, Marchese’s office — the criminal division of the attorney general’s office — was settling a case after an assistant attorney general reported hearing a call between an attorney and his jailed client. She said it was a rare, one-time error by the jail. But within weeks, a detective working on another case her office was prosecuting, reported hearing portions of two calls between murder suspect Nightingale and his attorney, John Tebbetts.

At Marchese’s request, Robinson sent a letter in July 2020 to the elected sheriffs reminding them that phone calls between inmates and attorneys cannot be recorded or shared. He wrote that investigators and prosecutors didn’t want those communications and were not entitled to possess them.

“We would ask that you keep track of all attorney contact information so we can reduce the number of attorney/client calls that are recorded and improperly provided to law enforcement and the state,” Robinson wrote.

Marchese considered the matter settled. It was beyond the control of her office, she said to The Maine Monitor in April 2021.

But within days a defense attorney’s calls were shared with state police in a murder case her office was prosecuting, records show. Then in August 2021, a cache of jail calls were shared with the child protection division of the attorney general’s office. The latter have since been deleted.

Marchese acknowledges attorney calls were shared with her office but insists that her office doesn’t use such calls.

“Nobody here is going to try to get a phone call and use it in court. You’d be disbarred. No judge would ever let you use it,” Marchese said. “It’s an annoyance, is what it is. We don’t want it. We’re irritated when we come across it.”

But when it does occur, there are no procedures to remove the person involved from the case.

The expectation is that prosecutors will report it to the defense, Marchese said.

The lack of a written policy runs afoul of national best practices, Kendrick said. And people with access to privileged material should be excluded from the case, she said.

“If I were the prosecutor and I wanted to make sure there was no question that it was a good investigation and that there was no taint from it, it seems that it would make sense to get a different investigator to do the rest. Because once the investigator has been listening to the attorney’s calls, that does call the whole investigation into question,” said Kendrick, the National Prison Project deputy director.

25 years to life

Before 1 a.m. on Aug. 13, 2019, a trooper responded to the scene of an accident on the side of State Road in Castle Hill, a rural town in Aroostook County with a population of 373 people. Two men in the cab of a Chevrolet Silverado pickup were shot dead.

Days earlier, police had responded to reports of a home invasion in Presque Isle. A man in a black ski mask had struck the apartment owner across the face with a gun — fracturing several bones around his eye — and fired a bullet into the bedroom wall. An officer at the scene said within earshot of the victim that the intruder “sounds like Bobby Nightingale,” court records show.

Nightingale was indicted with killing two men during a crime spree between Aug. 5 and 13, 2019 that included burglary and gun charges. The state claims a gun found at Nightingale’s house was used throughout. Nightingale denies he was the shooter and has pleaded not guilty.

Tebbetts, 33, moved to the county shortly after graduating from the Penn State Dickinson School of Law in 2014. He opened a law firm in Presque Isle — “the hub of Aroostook” — four years later and began taking on a steady stream of court-appointed cases. As best as he can recall, he registered his phone number with the jail. Most of the people Tebbetts represents cannot afford to retain him and instead have their legal services paid for by the state. Maine, unique among states, employs no public defenders.

When Tebbetts was first assigned to Nightingale, he was in the Aroostook County Jail in Houlton, where Tebbetts routinely visits with his clients. Without warning, Nightingale was transferred 288 miles away to Cumberland County. The nine-hour, round trip drive was nearly impossible for Tebbetts to do in a day on top of the demands of his law practice. Tebbetts had little choice but to talk to his client by phone.

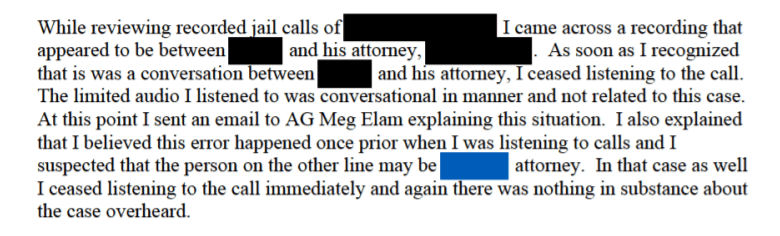

Neither man knew it then, but calls between them were recorded by the jail and shared with state police, the state attorney general’s office confirmed. The Cumberland County Jail sent audio of Tebbetts’ and Nightingale’s calls to Detective Gregory Roy of the Maine State Police, who discovered in early May 2020 that he possessed their calls. Roy said the “limited audio” that he heard was conversational in nature and unrelated to the case.

Roy heard two calls between Nightingale and Tebbetts before “I ceased listening,” he later told his superiors. Roy didn’t report the first call he found. The attorney general’s office advises they stop listening and to tell prosecutors, who in turn will inform the defense. After the second call between Nightingale and Tebbetts, Roy alerted Assistant Attorney General Megan Elam, one of the prosecutors on the case.

“Greg Roy was listening to some calls. He recognized that it was an attorney call, stopped listening, notified Meg, Meg notified the defense attorney,” Marchese said.

Tebbetts believed his calls were off limits to police. State prosecutors mailed him a CD and when he played it on his MacBook Pro his own voice filled the small office.

“I said some not nice words to the effect of, ‘What the fuck?’ ” Tebbetts said.

Nightingale suspects police got the name of a potential witness from comments he made to Tebbetts by phone. Now, he defaults to what he calls “double-talk” — hinting without actually saying what he wants to say — to guide Tebbetts toward ideas he won’t say outright for fear it will be overheard. The state says it has stopped listening to Nightingale’s calls, but he doubts it’s true.

Nightingale is being housed at the jail in Washington County, which is more than three hours and 160 miles away from his attorney, making phone contact his primary option to stay in contact with his attorney. When he arrived at the jail in August 2021, he had guards verify his attorneys’ phone numbers were blocked from being recorded.

“I don’t feel safe. I haven’t felt safe talking to my lawyers for over a year,” Nightingale said.

“I haven’t been able to tell them things that they want to know. Like when I read over discovery or I listen to stuff I can’t explain. I can’t tell them what I want to because I don’t know if somebody’s listening,” he added.

Elam denied listening to any of Nightingale’s calls to Tebbetts or that state police heard anything of substance during the calls, she said in response to written questions. The monitoring of Nightingale’s jail calls was routine and potentially valuable, she said.

“Occasionally defendants make incriminating statements despite the fact they are told by their attorneys not to discuss their case and that the calls are recorded,” Elam wrote.

When Nightingale and his attorney speak on the phone, they are discussing his defense and there’s no way that if someone listens to a phone call that they didn’t hear something that is privileged, Tebbetts said. He plans to challenge what the state heard in court.

Prosecutors gave Tebbetts many CDs of Nightingale’s jail calls. He hasn’t had time to go through all the discs, but prosecutors did ask him to listen to one disc to see if there were privileged conversations, said Tebbetts.

Jail records show more of their calls were downloaded at the Aroostook County Jail. Tebbetts does not know what happened to those recordings and hasn’t been notified of them. It’s one matter if the calls were mistakenly downloaded and deleted, it’s a “horse of a different color” if the additional calls were listened to, he said.

“If they haven’t crossed the line, they’ve come right up to it,” Tebbetts said of the state police’s investigation of his calls.

That his calls may be monitored has changed every aspect of Nightingale’s relationship with Tebbetts.

“The relationship is sacred between a lawyer and a client. You’re supposed to be, you have to trust them,” Nightingale said. “In this case, I have to trust them with my life, so if I can’t talk to them openly and honestly then how can we keep that trust?”

The recordings caused a stir within the state police. On Aug. 17, 2020, state police circulated a Maine Monitor article about Tebbetts filing a class action lawsuit in federal court against Securus Technologies for allegedly wiretapping lawyers at the jails. Roy sent an email reply to the group.

“My case is the impetus for this lawsuit,” Detective Roy wrote. “…I can see this blowing up potentially.”

The Maine State Police declined to make Roy available for an interview.

A state police official in an email to higher ups — including Colonel John Cote, chief of the state police, and to Deputy Chief Bill Harwood — expressed concern about attorney calls being shared with the agency.

“Clearly none of those calls/recordings are being turned over on purpose, but it does happen from time to time,” wrote Troy Gardner, lieutenant of the state police’s northern major crimes unit. Investigators always reported attorney-client calls, when they found them, to the attorney general and district attorneys, he added.

“The problem is that defense counsel is crying dirty pool and sort of suggesting that (law enforcement) is doing it on purpose and simply apologizing later,” Gardner wrote, in emails obtained by The Maine Monitor through a right to know request.

If investigators “unintentionally obtain” attorney calls, they are directed “not to listen under any circumstances,” wrote Shannon Moss, a spokeswoman for the state police. “We also immediately document the event and notify the prosecutor of exactly what happened. We take any and all appropriate steps to ensure we do not violate attorney/client confidentiality.”

State police would go on to listen to attorney phone calls in at least two more cases in 2020 and 2021 when an attorney didn’t register his cell phone number with a jail.

Eavesdropping on murder suspects

Coleman, 27, is accused of shooting Natasha Morgan, when she was 19, multiple times in her mother’s driveway while exchanging custody of their daughter. Witnesses told police the young couple had broken up the night before the violence, according to court records. Morgan was rushed to Central Maine Medical Center where she died of her injuries. Coleman fled to Mississippi and was extradited to Maine.

On Oct. 15, 2020, state police Detective Abbe Chabot was listening to recordings of Coleman’s jail calls when he heard him speaking to his attorney Verne Paradie. Chabot stopped the recording but didn’t write down which file contained the conversation. He continued to listen and heard a second call. This time it took “several seconds” for Chabot to recognize Paradie and Coleman’s voices again.

Documents show that calls Coleman made between Aug. 1, 2020 and Sept. 22, 2021 were requested by and provided to the Maine State Police.

Coleman’s trial is scheduled for May.

Six months later, another state police detective heard Paradie speaking with a client at the Androscoggin County Jail. This time the client was Nur, a 21-year-old, who police had investigated multiple times. Detective Lauren Edstrom listened long enough to hear the men discuss whether to get a transcript of a call, before she realized it could be Nur’s attorney on the phone.

Prosecutors claim Nur fired a gun, which killed Hassan Hassan on Oct. 31, 2020. However, clothing matching a description a witness provided police and recovered from a dumpster doesn’t match Nur’s DNA, according to court records. Paradie challenged the credibility of the state’s case.

He argued the state failed to disclose the witness had told police multiple people fired guns on Halloween night, according to court records. A judge denied Paradie’s request to dismiss the case in April 2021.

Shackled at the wrist and ankles with three sheriff deputies standing guard by the exit, Nur appeared in the Androscoggin County Superior Court next to his attorney on Dec. 1, 2021.

Paradie again challenged whether the state had enough proof to support that Nur was the shooter and attacked the credibility and motives of the state’s witness. A judge denied Nur and his attorney’s requests on Dec. 7.

Blaming attorneys

Whenever attorney calls are released to prosecutors, officials often blame the attorneys for not making sure that their phone numbers are on the jail’s do-not-record list.

However, there is no uniform, statewide process to get a phone number blocked at a Maine jail. Contracts signed with Securus Technologies say it is the county jail administration’s responsibility to track and make private attorneys’ phone numbers, but since reports surfaced of attorney calls being recorded, several jails now rely entirely on the company to block the recordings.

Androscoggin County Jail recorded 91 calls to the Lewiston law firm Paradie, Rabasco & Seasonwein between June 2019 and May 2020. The phone number was blocked from being recorded along with more than 400 attorney phone numbers in the spring of 2020. One number not made private was Paradie’s cell phone, which had negative consequences for his clients.

Nur had called his attorney’s cell phone. The jail phone provider, Securus Technologies, then released Nur’s calls to detective Edstrom twice without realizing attorney calls were among the recordings, police records show.

Edstrom sounded the alarm to Androscoggin County that the jail was recording an attorney. Sergeant Victoria Langelier, the jail’s program director, said it was the defense attorney’s job to register phone numbers with Securus Technologies, not the jail’s.

What happened with Paradie’s cell phone illustrates how any misstep by a defense attorney, jail official or defendant in making a phone number private can allow a confidential call to slip through, be recorded and heard. Paradie’s cell phone is now on the jail’s do not record list.

Uncovering which calls and what information the detectives heard has been a frustrating task ever since, Paradie said. He asked for specifics on what calls were listened to and got only date ranges requiring him to listen to many calls from that period.

“I still don’t know what they heard,” Paradie said, nine months after being told his calls were listened to. “They’re telling me they heard stuff, but they’re not being clear on what it was they actually heard. I don’t know what I would ask for from the court.”

Paradie considered challenging in court the state police’s access to calls to him from Coleman and Nur, but decided against it.

“My understanding is they stopped listening as soon as they realized it was me, which was fairly soon in the process,” Paradie said. “Had I thought that they heard something they should not have, I certainly would have challenged it.”

The bar is high to bring a court challenge, he added.

“We have to show that they were intentionally trying to record and listen to our phone calls and then we have to show that they didn’t stop when they realized it was us and they heard stuff they shouldn’t have heard,” Paradie said. “And then we have to show what they heard. I don’t know how we would go about doing any of those things.”

The defendants’ best chance is to get the information thrown out by the trial judge, because the burden of proof will be much higher if they appeal later, legal experts said.

It all hinges on knowing what the government heard and how it was actually used, Tebbetts said.

“The law hasn’t caught up with the facts,” Tebbetts said. “I don’t think anyone contemplated that there could be endemic levels of listening to phone calls.”

Tebbetts and two other attorneys filed a class action lawsuit against Securus Technologies in August 2020 for allegedly breaking federal and state wiretap laws by recording attorney phone calls. A federal judge dismissed the complaint in November 2021 for failing to show the company intentionally singled out lawyers’ calls.

For years, defense attorneys self-reported their phone numbers to each jail or relied on clients providing the information on paper to be manually entered by jail supervisors. An unchecked box can mean the difference between a call being recorded or not recorded.

A spokeswoman with Securus Technologies declined multiple requests to answer The Maine Monitor’s questions.

It should be clear to callers when they are being recorded by a jail, Gabriel Colwell, legal counsel for Securus Technologies, wrote in an October statement to The Maine Monitor.

“Recipients of calls from correctional facilities in Maine using Securus telecommunications equipment have always been admonished — before a call begins — that their calls are subject to recording and monitoring,” Colwell wrote. “…In every instance, the call recipient has the option to continue with or decline the call after hearing the admonishment.”

The recording does not play if the attorney has made their phone number private with the jail, he said.

‘Trying to find dirt on this family’

Recorded phone calls were even released by the Franklin County Jail to the state Office of Child and Family Services in a civil case in August 2021. Taylor Kilgore, attorney for the defendant, said she was shocked at how easily the state got access to the recorded calls which involved a colleague.

The state ultimately acknowledged that two supervisors with the Office of Child and Family Services listened to hours of jail calls, calling the breach a “mistake.”

“There was one mistake. A mistake is not misconduct,” Nora Sosnoff, director of the child protection division of the attorney general’s office, wrote in an email to The Maine Monitor. Her office provides legal services to the Office of Child and Family Services.

Kilgore said even if the attorney-client calls weren’t in this set of calls, “I don’t know why the department thought that this was helpful or relevant to them at all. They just decided to pull these recorded calls — to use a term that you hear on TV a lot — as a fishing expedition. They seem just to be trying to find dirt on this family.”

The Office of Child and Family Services has destroyed the attorney calls and is reviewing its process, said Jackie Farwell, a spokeswoman for the agency. It is rare for parents to be jailed while being investigated for child abuse or neglect. It is also uncommon for investigators to request their phone calls, she added.

Ashley Perry, who joined the civil case as co-counsel in the fall, said they were still trying to determine the chain of events that led to the release of the recordings. Separately, calls to Perry’s law firm from two jailed criminal defendants were recorded 10 times by the Franklin County Jail in 2019 and early 2020, records show.

“I, maybe naively, thought that if it was recorded it still couldn’t ever be obtained and used against a client,” Perry said.

Tipped scales of justice

Prosecutors need search warrants or subpoenas to access the phone calls of defendants who are not being held in jail. But for defendants in jail, law enforcement officers are just a few clicks away from listening to every one of their conversations that is not to an attorney.

“If you’re out (of jail) and at home and make a phone call, they don’t have the power, without any legal basis or permission, to just grab and listen to that call,” said Bina Ahmad, a civil rights lawyer and former New York public defender.

That Maine prosecutors and law enforcement were listening to attorney calls was almost unfathomable, she said. Ahmad said she would try to dismiss any case where prosecutors or guards listened to the attorney. There is no way to guarantee privileged information won’t be used against a defendant once it is released.

The burden falls heaviest on low-income suspects who remain in jail because they can’t afford to make bail or suspects facing the most serious charges, which carry the greatest threat of long-term incarceration. An estimated 555,000 Americans are held in a confined setting prior to trial. Almost all of them are kept in local jails, according to the Prison Policy Initiative.

The financial and social costs of incarceration are high and can affect the eventual plea deal or sentence a person is offered, said Elizabeth Simoni, the executive director of the nonprofit Maine Pretrial Services, which arranges for people to have supervised release from jail, sometimes in lieu of bail.

“There is always a group of people, who if they had access to financial resources, they would not be waiting in jail. Always,” Simoni said. “…People do literally languish in jail because they do not have access to the financial component.”

As a murder suspect, Nightingale didn’t get the chance to make bail. He’s been in county jail for 29 months waiting for his trial, which is tentatively scheduled for August 2022.

Nightingale’s teenage daughter Serenity wrote to him recently lamenting the time she missed with him growing up because he was in jail on other charges. When he thinks about getting a life sentence, he thinks of her and the people in his life he won’t be able to support.

“If I get found guilty, this is a life sentence. It’s not going to be anything else.”

It troubles Nightingale to think a detective listened to enough of his jail calls to recognize his attorney’s voice. He fears the government will use what it heard to convict him of a crime he says he didn’t commit.

“This is the rest of my life,” Nightingale said.

This reporting is also supported by The Pulitzer Center, Report for America, and Investigative Editing Corps.