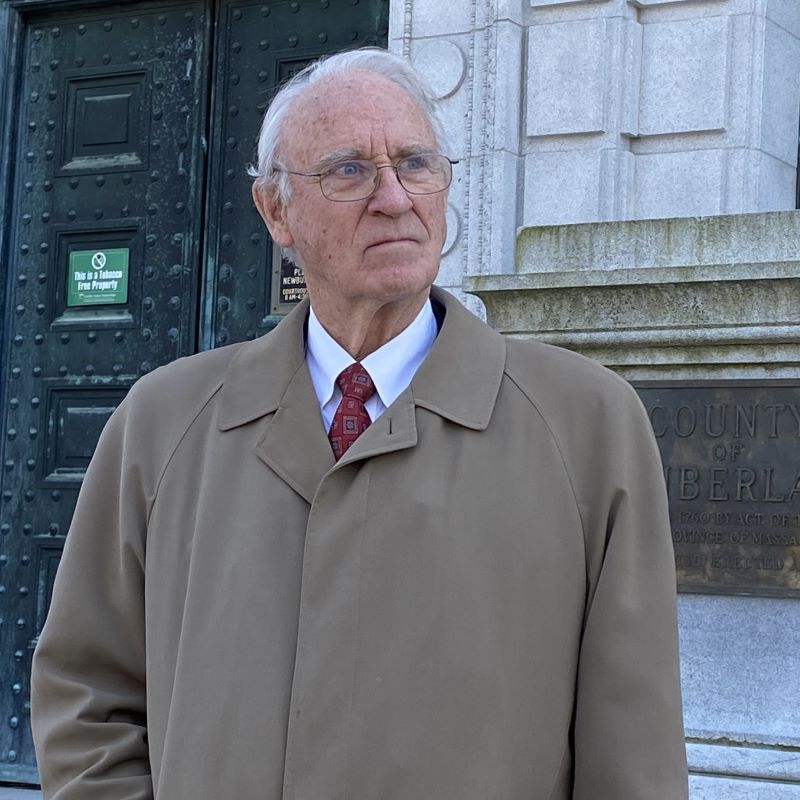

When Thomas Cox’s complaint against a Maine Supreme Judicial Court judge is decided, it will likely happen without his knowledge.

Cox, a longtime foreclosure attorney, made the unusual move of lodging a complaint against Associate Justice Catherine Connors in late January after the judge heard two consequential mortgage cases: Finch v. U.S. Bank, N.A., 4-3, and J.P. Morgan Mortgage Acquisition Corp. v. Moulton, 5-2, both eventually decided in the lender’s favor.

For decades, Maine’s legal precedent prohibited banks from suing borrowers for defaulting on their loans a second time if the first case was dismissed because a proper notice of default was not issued. The precedent was upheld in two cases in 2017, Fannie Mae v. Deschaine and Pushard v. Bank of America.

The recent decisions in Finch and Moulton overruled these rulings — upending precedent that foreclosure attorneys and housing advocates say was a critical safeguard for Maine homeowners.

Connors, who was appointed to the state’s highest court in 2020, worked on the 2017 cases for the lenders, representing Bank of America in Pushard and co-authoring a brief for the Maine Bankers Association in Deschaine.

Cox and other legal experts said she should have recused herself from the recent cases that overturned precedent in favor of the lenders. Now Cox is pushing for transparency, asking that his complaint against Connors be decided in the open.

Cox believes the reversals will undermine mortgage law and enrich Connors’ former clients. He pointed to federal case law that says a judge should recuse herself if a “reasonable person” thinks it would be appropriate to do so.

“Even though a decision on this complaint cannot by itself undo the damage resulting from Justice Connors’ conduct, a resolution of the issues raised may prevent further damage,” he wrote.

But in Maine’s judicial system, the recusal process and internal ethics proceedings are shrouded in secrecy. A complaint lodged against a justice plays out behind closed doors, unless the judge chooses to waive confidentiality or the disciplinary body votes to open the case.

While some legal experts say confidentiality is necessary to protect certain parts of the investigative process, they caution that too much secrecy can undermine the public’s confidence in the judicial system.

Maine in the minority

David Sachar, the director of the National Center for State Courts’ Center for Judicial Ethics, compared Maine’s judicial misconduct process to the grand jury process; the public has no idea what charges will be brought to trial until the jury determines if the allegations meet the standard of proof. He said there are good reasons for confidentiality.

“You don’t have access to grand jury records while they’re considering whether to charge somebody or not, or even criminal records while the case is ongoing,” Sachar said. “The real rub is when does the public get to know about what’s going on?”

“It’s best practice if we can disclose, to disclose,” he later added, speaking about recusal. “But it doesn’t always happen that way.”

The complaint process puts Maine in the minority, according to the National Center for State Courts. Thirty-five state judicial disciplinary bodies make their fact-finding hearings public; Maine and 14 others only make their findings public if discipline is recommended.

A 2016 report from the Brennan Center for Justice found that most states rely on judges to decide if recusal is necessary, do not require judges to give a reason for recusal and do not permit an independent review of outside requests for recusal.

Dmitry Bam, the vice dean of the University of Maine School of Law, called the recusal process “unconstitutional” in a 2015 article, noting that it violates the idea of an impartial judicial system by allowing a judge to determine their own bias.

“We should not be surprised that judges have not declared the practice unconstitutional, as judges themselves have an interest in its continued existence,” Bam wrote.

Complaints against a Maine judge go to the Committee on Judicial Conduct, which reviews grievances and recommends discipline. The group is made up of three judges from probate, district or superior courts, who are appointed by the Supreme Judicial Court, and two lawyers and three members of the public recommended by the governor.

The committee meets every two or three months and only sees a few dozen cases each year. There were an average of 38 complaints filed each year between 2013 and 2022, according to a committee report.

Most cases resulted in a finding that no violation occurred, and were closed without questioning the judge the complaint was directed against. If the committee does refer the complaint to a judge, it can decide whether to investigate further once the judge responds. After the investigation stage, the committee can report a judge to the Supreme Court or dismiss the case with or without a reprimand.

If the committee decides to report a judge to the Supreme Court, all proceedings from that point on are public. The court can then assign one justice to hear the complaint or set a trial date before the full court. (Connors would not participate in a hearing if she were the subject of the complaint, judicial system spokesperson Barbara Cardone said.)

Cox said the Supreme Court justices should not decide Connors’ case because he felt her colleagues could not be impartial. He called for the Supreme Court to appoint at least three special justices to oversee complaints against its judges.

The last time the committee pursued disciplinary action was 2018, when it reprimanded former York County probate judge Robert Nadeau for deciding a child support case after his wife allegedly posted about the woman on social media. This followed a suspension for other misconduct.

“A breach of trust”

Cox told Cathy DeMerchant, the chair of Maine’s judicial conduct committee, that he understands that most hearings do not need to be public, but this case is unique.

“A complaint against a justice on this state’s highest court is another matter, particularly where the conduct has been decisive in changing prior law,” he wrote in a Feb. 16 letter. “A public hearing is the surest way for Maine’s citizens and legal community to be confident our judicial system is being held to the highest standards of integrity and transparency.”

Cox said he has not heard from the committee about his complaint or his request to have it heard openly. He said he also sent letters to Gov. Janet Mills’ chief counsel, Jerry Reid, and Chief Justice Valerie Stanfill, asking that they weigh in on the issue, but has not received a response.

Ben Goodman, a Mills spokesperson, said her office had not received the letter until it was forwarded by a Maine Monitor reporter. He said the governor will not comment on the committee’s independent proceedings.

Before oral arguments, Cox pushed for Connors to sit out the Moulton case.

So did then-Rep. Jeff Evangelos, I-Friendship, who was on the legislature’s judiciary committee. He requested in an October 2022 letter that she recuse herself, pointing to Connors’ confirmation hearing testimony, in which she said she would recuse herself if a case with a prior client arose.

“I came away from (Connors’ confirmation hearing) believing she had agreed to recuse herself,” Evangelos said. “So when she didn’t, that’s a breach of trust.”

Maine’s judicial code says judges should recuse themselves if they “served as a lawyer in the matter in controversy, or (were) associated with a lawyer who participated substantially as a lawyer in the matter during such association.”

But Cardone told The Maine Monitor that organizations that file amicus briefs should be considered differently because they are not named in a lawsuit and do not have rights at stake. They only serve to “bring to the court’s attention some of the broader implications of pending litigation,” she said.

Several lending institutions filed amicus briefs in the Moulton case, including the Maine Credit Union League, Federal Housing Finance Authority and Maine Bankers Association — Connors’ client in Deschaine. Housing advocates also weighed in, including Maine Equal Justice, Pine Tree Legal Assistance and the National Consumer Law Center, which Cox serves as counsel.

Cox said he is less concerned with what role those institutions played in the cases than the fact that Connors has a long history of representing banks in foreclosure matters, again pointing to the ethics code: “A judge shall disqualify or recuse himself or herself in any proceeding in which the judge’s impartiality might reasonably be questioned.”

Rules of reason

Robert Tembeckjian, the administrator and counsel for the New York State Commission on Judicial Conduct, said Maine’s judicial code and the American Bar Association rules are meant to be a starting point for conversations about when recusal is warranted.

“No code could catalogue all of the possibilities,” he said. “Indeed, the preamble to the code says it is not intended to provide ‘an exhaustive guide’ of conduct to avoid, and the code itself comprises ‘rules of reason.’ ”

Like Maine, New York keeps its judicial conduct proceedings secret unless disciplinary action is taken. After years of resistance, Tembeckjian said a bill before the New York legislature may change that.

“If you have a process that is cloaked in secrecy, and the final result can be secret, there’s no guarantee to the public that the disciplinary body is discharging its responsibilities in a fair and responsible manner,” Tembeckjian said.

Tembeckjian said any instance where a client that a judge previously represented came before the court would invite questions about recusal.

“It’s very difficult to imagine that the judge’s impartiality wouldn’t at least appear to be in question if there was a party that the judge had recently represented now before the court,” he said.

Robert Cummins, a Maine lawyer who helped draft the American Bar Association’s Model Code of Judicial Conduct, called it “surprising” that Connors did not step away, given her history and what it would suggest to the public.

“The judge’s impartiality in those specific cases could have — and most certainly should have — been questioned,” he said.

But he also blamed the lawyers for not pushing for it.

“That lawyers’ failure to protect client interests may have influenced the judge’s decision not to step away,” he said.

Kendall Ricker, the attorney for Buckfield resident Camille Moulton, whose foreclosure proceedings were at the center of one of the recent cases, said he did not see a clear rule requiring Connors’ recusal and felt her fellow judges would not require her to.

Ricker said it would be “detrimental” to assume a judge could not be impartial when hearing a case involving a former client, noting that it’s a lawyer’s job to represent a client, not hold their views.

“Three other justices held the same position as Justice Connors,” he said. “If Justice Connors was truly advancing an illogical and biased position, then such positions would have been a dissent, not the majority opinion.”

State legal organizations seem disinclined to join Cox’s objection. Angela Armstrong, the executive director of the Maine State Bar Association, said the group’s governing board voted against petitioning the judicial conduct committee to open the proceedings, noting they believed they should not have been informed of the complaint given confidentiality rules.

Regardless of whether Cox’s complaint gains traction, the effects of the overturned mortgage cases will be felt across the state.

In their dissent, Associate Justice Andrew Mead, and former justices Jeffrey Hjelm and Thomas Humphrey, said the court overturned Deschaine and Pushard simply because it disliked the 2017 rulings, not because the state law that underpins them had changed. They argued the ruling could lead to concern about the court’s reasoning.

“I submit that the willingness of the court, as currently composed, to overturn considered and entrenched legal precedent,” the justices wrote in the dissent, “may raise questions among the public about the extent to which it will feel restrained in departing from precedent in other areas of the law.”

Correction: Due to an editing error, this article originally transposed the decisions in Finch v. U.S. Bank, N.A. and J.P. Morgan Mortgage Acquisition Corp. v. Moulton. Finch was decided 4-3 and Moulton was decided 5-2.