Like most states, Maine guarantees parents legal representation when removing their children from their homes because of fears of abuse or neglect.

Since the start of the year, the daily list of parents waiting for an attorney has grown 400 percent, according to the Maine Commission on Public Defense Services (MCPDS), which oversees the assignments.

The growing number of cases is having an effect on parents and children, advocates said. Under Maine law, the state must provide a hearing within 10 to 14 days after removing children from a home, at which point parents may respond to accusations about their care.

Family law attorneys said some cases are being delayed while parents wait for legal representation, meaning some parents are going weeks or even months without an attorney while their children are with foster parents or family members.

“What’s happening across the state right now is that there aren’t attorneys at that 10- to 14-day mark,” said Taylor Kilgore, a Turner-based parent attorney. “So those parents’ first opportunity to be heard, and their first opportunity to try and get their children back, often doesn’t happen.”

How long parents are waiting is hard to determine: Several state agencies were unable to provide data, and confidentiality makes it difficult to track and identify child protective cases.

But the number of child protection cases in need of attorneys on any individual day has skyrocketed, from 14 on Jan. 3 to 70 by mid-April, according to the MCPDS.

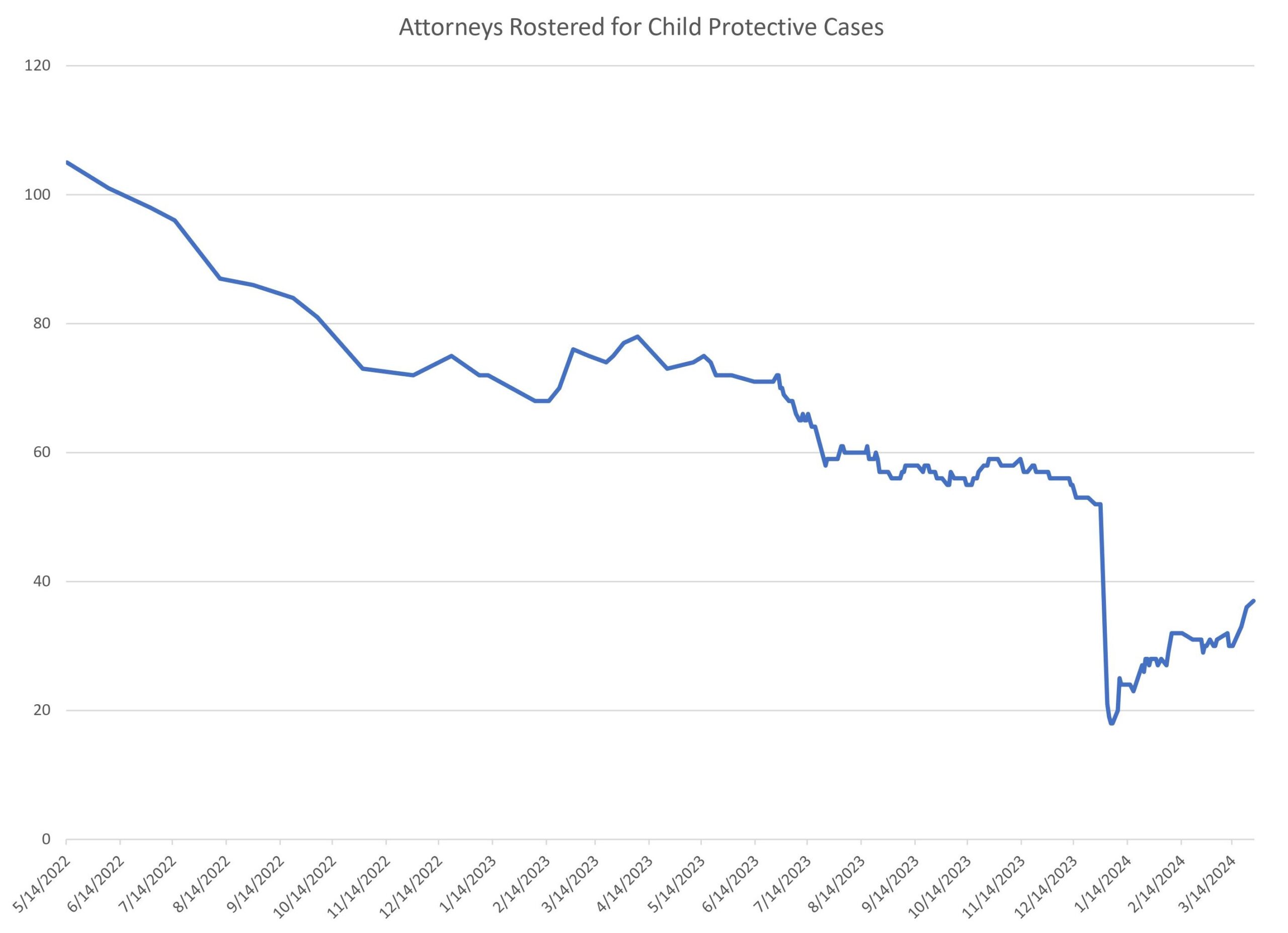

At the same time, the number of attorneys able to take cases each day has fallen since MCPDS, formerly the Maine Commission on Indigent Legal Services, began tracking in May 2022. There were more than 100 names on the roster then. That number fell to less than 20 by the beginning of 2024, before rebounding to the mid-30s by the end of March.

A shrinking number of available attorneys is intertwined with the rising number of cases awaiting representation. As attorneys retire, leave the field or max out their caseloads, they are taken off the roster, resulting in fewer who are available.

The dearth of attorneys able or willing to represent parents in child protection cases not only delays some parents’ chance to argue for the return of their children, but extends the time children are in state custody.

Delays also can prevent the implementation of support services and visitation arrangements, as well as the opportunity for parents to take steps to alleviate concerns about the safety of their homes.

While some children will eventually be permanently removed, adopted or sent to live with relatives, many will ultimately return home. Roughly 50 percent of removed children will be reunited with their families.

A lack of lawyers is keeping children and their families apart longer than necessary, said Julian Richter, president of the Maine Parental Rights Attorneys Association and a member of the Maine Child Welfare Advisory Panel.

“The longer a case goes on and the longer a child is outside of the parents’ custody, the harder it is to integrate back into the home,” said Richter.

Several experts said Maine’s inability to provide timely legal representation to parents – who are overwhelmingly unable to afford their own lawyers — raises larger questions about the relationship between parents’ rights and the well-being of the state’s children.

“Empirical evidence shows that if you have high-quality representation for parents, it’s better for kids,” said Christine Gottlieb, director of New York University’s Family Defense Clinic. “The idea that you’re protecting the parents’ rights at the expense of the kids just isn’t accurate.”

State under pressure after high-profile deaths

The Maine Department of Health and Human Services, which oversees child welfare cases, has been under significant pressure after several high-profile deaths of children, some of whom had been in state care and returned to their caregivers.

The scrutiny began in earnest in 2018 after 10-year-old Marissa Kennedy died of abuse after years of DHHS involvement. That year the department took 30 percent more kids into foster care than the year before.

The widely covered case, and others that followed, increased calls for reform and referrals from the public to the department.

Lawmakers recently backed the idea of creating a separate child welfare department to fix what some called a broken system. Gov. Janet Mills has said she wants an in-depth review of the proposal, which faces additional votes in both chambers.

“I think the department is under significant political pressure to remove kids to be on the safe side,” said Jim Billings, executive director of the Maine Commission on Public Defense Services. “That tends to create more cases and can make (them) more contentious if you’re removing kids from the outset on a marginal case.”

In Maine, 74 percent of removals were associated with neglect in 2022, according to federal data, higher than the national average of 64 percent. Roughly 11 percent of removal cases involved concerns about physical abuse, below the national average of 13.

When parents have quality legal representation, children spend less time in foster care without increased risk to the child, said Gottlieb, of New York University’s Family Defense Clinic. In addition the state saves money because it isn’t paying for foster care.

“It’s a win-win.”

Without legal representation, parents are thrown into a process they don’t understand and the state is poor at explaining.

A legislative oversight committee found that caseworker conversations with parents about their needs and case planning goals “tended to fall short of expectations,” according to a report on the family reunification process published in February.

Parents and their representatives told the committee that “caseworkers fail to address the key question of what the parent is doing or needs to do to move closer” to meeting state expectations and reuniting with their children.

Aging bar, recruitment impact roster

At the beginning of 2024, MCPDS instituted a point system that limited the number of cases attorneys could accept. Too many points and they are removed from the daily roster.

The measure was meant to prevent attorneys from taking on more cases than they were able to handle, reducing burnout and improving the quality of representation. But in the short term, the measure has resulted in fewer attorneys to take cases.

“That’s really where this issue is coming from,” said Chelsea Peters, an Auburn-based attorney. She also said the problem has been obvious for years as older attorneys retire faster than younger ones enter the profession.

“I’m almost 42, and I’m probably the youngest attorney in my county who’s practicing,” Peters said. “There are no new attorneys coming in this area of law.”

An aging parents’ attorney bar and a lack of structures to recruit law students and young lawyers are problems in many places, not just Maine, said Vivek Sankaran, director of the Child Law Advocacy Clinic at the University of Michigan.

“Maine is just a microcosm of what’s going on across the country,” Sankaran said. “In a lot of places they either have a shortage of lawyers, or there are delays, and it could be weeks after a case is filed, after a kid’s been removed, that a lawyer is actually appointed.”

The growing backlog of parents waiting for legal representation mirrors the growing problem of indigent criminal defendants waiting for attorneys, which has prompted legislative action and the rollout of public defender offices.

But while most of those criminal defendants are out on bail, the parents waiting for legal representation remain separated from their children while they wait.

In August, Maine Supreme Court Chief Justice Valerie Stanfill wrote a letter pleading with some of the state’s largest law firms to help represent criminal defendants and parents in child protective cases.

Stanfill noted that the legislature had nearly doubled the hourly rate for attorneys taking those cases from $80 to $150 an hour, which took effect in March 2023. But the pay bump wasn’t having an effect.

“Last week there were over 100 cases pending in which a person is entitled to appointed counsel and for whom no attorney is available,” Stanfill wrote in her letter. A gap of 100 cases showed “the crisis is worsening,” Stanfill wrote at the time.

Stanfill’s plea doesn’t seem to have helped. The 100 combined criminal and child protection cases that represented a “crisis” in August ballooned to more than 800 cases by mid-April, according to the MCPDS.

The state has taken steps to address the criminal defense side of the crisis. Last year the first public defender office opened in Augusta.

And last month Mills signed a law establishing a public defender’s office in Aroostook County, and another that would serve Piscataquis and Penobscot counties. The bill also added positions to the Maine Commission on Public Defense Services.

Billings, the commission’s executive director, hopes to create full-time parent attorney positions as the state builds out its public defender network, he said.

Proposal for pre-petition representation fails

Legislators have made efforts to provide attorneys earlier in child protective cases. In 2021, the state created a commission to study the possibility of launching a program that would provide some parents with attorneys early in the DHHS investigative process.

The program would have provided what’s known as “pre-petition” legal representation, meaning parents would be assigned lawyers after DHHS was involved with their families, but before the department filed a petition for the removal of the children. The model has been implemented in a handful of states.

In its final report, the commission said the program had “the potential to reduce the number of children who are removed from their parents and custodians by helping to alleviate many of the conditions of poverty — for example, housing instability, difficulty accessing needed services and benefits, and domestic violence — that can contribute to parents’ and custodians’ inability to provide safe and stable living situations for their children.”

The commission proposed a two-year pilot program to provide legal representation to 30 indigent parents across Androscoggin, Franklin and Oxford counties. The free representation would have been coupled with data collection to understand the impact pre-petition legal representation had on families.

After the commission published its report in December 2022, Rep. Holly Stover introduced a bill to implement the project based on the commission’s report.

Melissa Hackett of the Maine Children’s Alliance testified in support of the legislation. “This is an important step to ensuring parents have the information and legal support they need to navigate their case and to work to address challenges so their children can safely remain with them,” she wrote in her testimony.

But before the vote, the MCPDS “submitted a letter to the Judiciary Committee indicating it did not have current capacity to take on the pilot project,” according to the Maine Child Welfare Advisory Council’s most recent annual report, published in January.

The bill failed.

Instead of getting an attorney earlier in the process, as the commission envisioned, parents are waiting longer as the process unfolds.

That process can be overwhelming.

When children are removed, parents get served with a petition or court order, according to Molly Owens, a Machias-based attorney. That document should have the name and number of an attorney they can call.

“When folks get that petition without an attorney’s name on it, and it has a court date within the next 14 days? I can’t imagine how terrifying that is,” Owens said.