Republicans are gearing up to challenge Gov. Janet Mills’ emergency powers this week in a battle that some experts and former governors from both parties say is largely political.

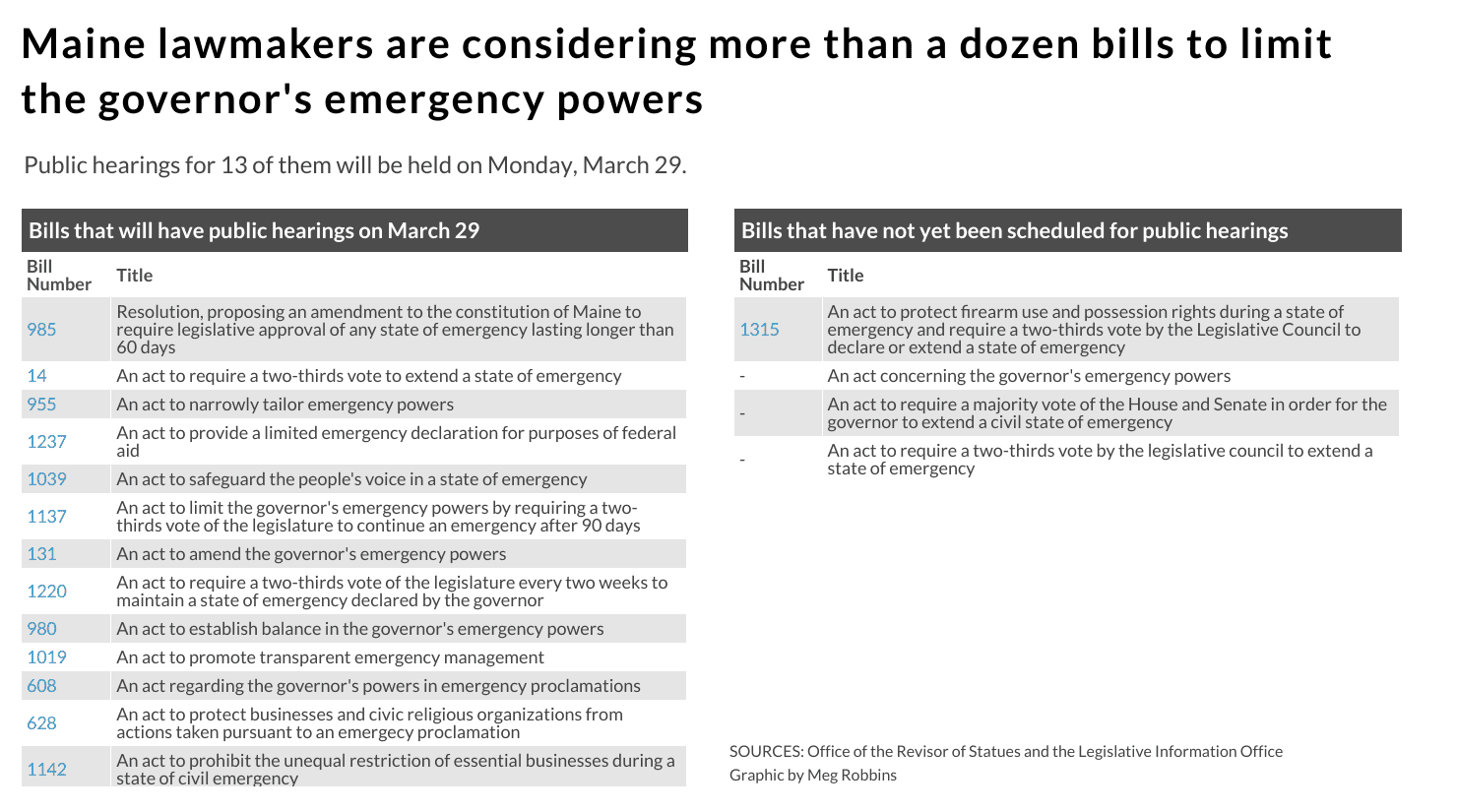

The State and Local Government Committee is scheduled on Monday to consider more than a dozen pieces of legislation that would require either legislative approval of certain restrictions proposed by the governor during an emergency or a vote of the Legislature to extend an emergency beyond 30 days. The Republican-sponsored bills are in response to the broad use of the governor’s emergency powers during the coronavirus pandemic.

For the past year, Mainers have lived under a state of emergency intended to slow the spread of the coronavirus. Administration officials say the emergency status — which enables the governor to temporarily assume more authority — is necessary to maintain the state’s response to a pandemic that has killed at least 730 Mainers and more than half a million Americans.

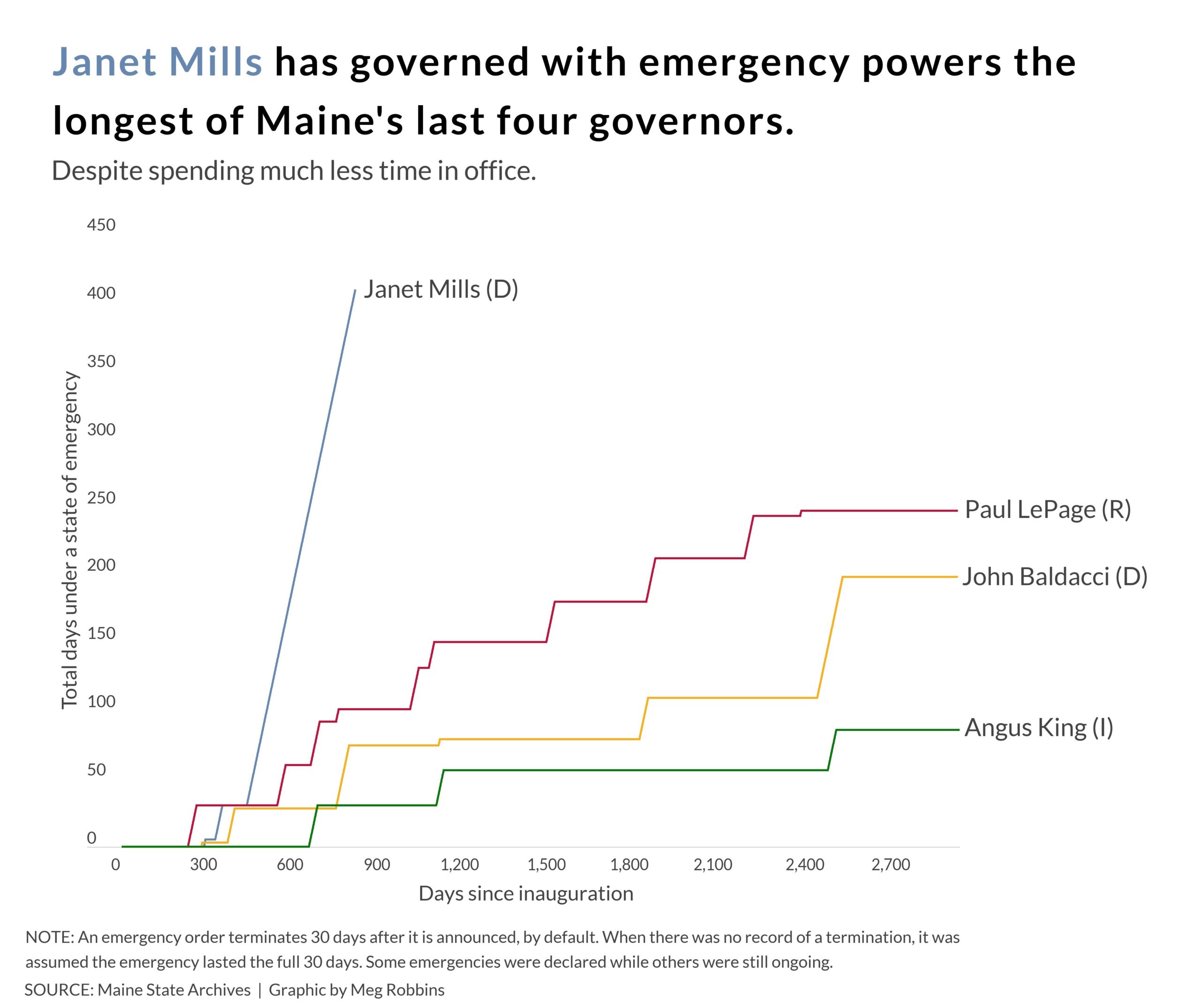

Mills has extended the emergency 13 times and imposed at least 78 executive orders since declaring an emergency on March 15, 2020.

Lindsay Crete, the press secretary for the administration, said Mills was not interested in politicizing the pandemic. The administration provided a written statement two weeks after The Maine Monitor requested an interview with Mills to discuss her use of emergency powers.

“When the governor took office, she never thought she would have to declare or maintain a state of emergency for such an unprecedented length of time. But she, like everyone else, also never thought we would be confronting such an unprecedented pandemic,” Crete said.

Former Gov. John Baldacci, a Democrat, said Mills responded well to the coronavirus pandemic. But the added power a governor receives during an emergency needs to be balanced with communication with the Legislature, he said.

“It’s like crying wolf. You don’t want to use it more than is necessary because then it loses its effectiveness,” Baldacci said.

The first order Mills declared suspended gatherings of more than 10 people and closed restaurants and bars. As the pandemic wore on, she added a mask mandate, business curfews and quarantine rules for out-of-state visitors — all with limited input from lawmakers, members of the Republican party told The Maine Monitor.

Stifled communications between the governor and Republicans prompted House Minority Leader Kathleen Dillingham (R-Oxford) to introduce a bill that would force Mills to talk to the Legislature. Dillingham has been allowed to speak directly with Mills only a handful of times. Often, Dillingham said, she was redirected to staff, who at least once said it would not be “productive” for her to speak to Mills about the pandemic restrictions.

“I can’t even quantify the number of emotions and thoughts that went through my head when that was what I was told,” Dillingham said. “Any time there is a conversation, it is productive. Even if at the end of the conversation those participating still have different viewpoints — understanding or at least hearing the grievances is productive.”

Crete denied that Republicans had not been able to access Mills during the pandemic. Mills and staff speak with the presiding officers and Republicans regularly on top of weekly breakfasts with lawmakers of both parties, she said. The administration has also responded to many suggestions, concerns and information requests from lawmakers.

Former Gov. Paul LePage, a Republican planning to run for governor again in 2022, said Mills inappropriately cut legislators out of pandemic decisions and the state needs to consider new checks on the governor’s emergency powers.

“Politics in recent years has been devastating,” he said. “It’s awful. It’s vicious. It’s a blood sport. But you still have to depend on the elected people to make sound, good decisions. And I personally have never had an emergency where the Legislature didn’t react positively.”

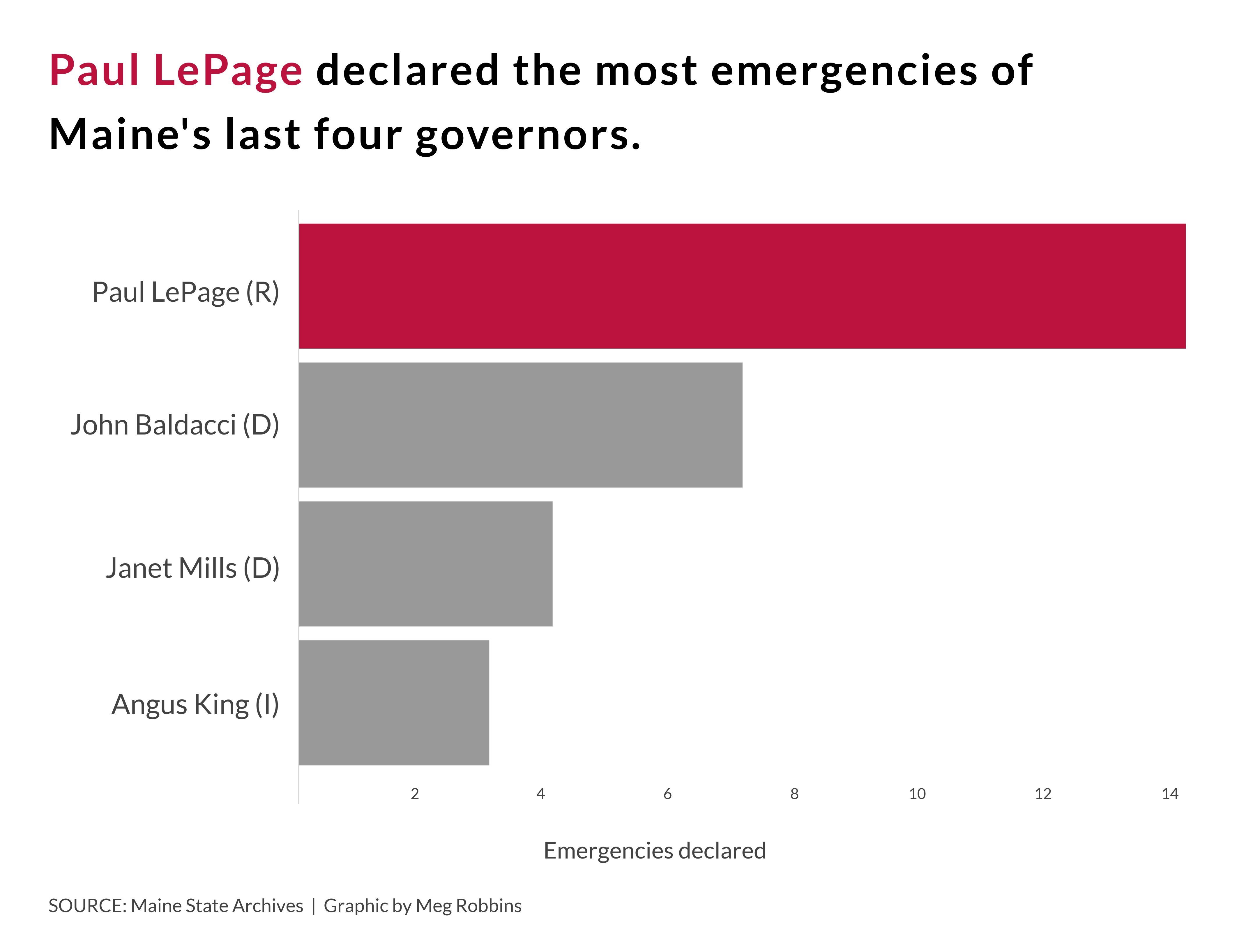

At least 28 emergency proclamations have been made in the past 24 years by the four most recent governors: Mills, LePage, Baldacci and Angus King, according to records obtained from the Maine State Archives and reviewed by The Maine Monitor.

The vast majority of emergencies were declared in response to storms and natural disasters. Fewer were in response to man-made events, including federal and state budget shutdowns in 2013 and 2017, respectively, under LePage. Fuel needs also prompted several governors to take emergency action.

Maine’s Constitution grants the governor the power to unilaterally declare a state of emergency. There is no limit on the amount of 30-day extensions that can be issued. The Legislature can order the governor to terminate an emergency at any time by a majority vote in both the House and Senate.

Lawmakers voted against ending the current state of emergency earlier this March, but the debate raised fundamental questions about how to balance power between Maine’s legislative and executive branches while also combating a fast-moving virus.

Rebalancing powers

Lawmakers in at least 41 states introduced bills in 2021 to limit or provide oversight of gubernatorial powers, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

These efforts vary significantly between the states, said Polly Price, a professor of public health law at Emory University in Georgia. Some proposed laws would require increased reporting by the governor while others would eliminate parts of the governor’s authority. The “overwhelming” majority of bills were introduced by Republicans, she said.

“To some extent it is a strategy that is a rejection of these kinds of broad-based social-distancing measures that many governors impose,” Price said.

Most state disaster laws date to the 1940s and 50s. They were designed for short-term emergencies like hurricanes, tornadoes, fires and earthquakes — not necessarily pandemics, according to Price. Given the circumstances, it’s understandable that legislators want more oversight, she said.

In Maine, most of the proposed legislation would require a majority or two-thirds vote of both the House and the Senate to extend an emergency beyond 30 days. One of the most extreme bills would limit the emergency proclamation to seven days before the full Legislature must weigh in.

The governor’s powers in an emergency are broad. He or she can suspend enforcement of laws; control movement in and out of disaster areas; purchase supplies; reassign state agencies and employees to perform emergency services; and take a number of other actions. Mills, LePage and Baldacci have each declared emergencies after severe storms to enable electrical line repairmen to work longer hours.

Sen. Trey Stewart (R-Presque Isle), who has proposed a constitutional amendment that would require legislative approval for any emergency lasting longer than 60 days, said he was not concerned by the mix of possible reforms. The Republican party’s concern is how Mills has used her emergency powers, including travel guidelines and her perceived unwillingness to work with legislators, Stewart said.

“The real crisis is so many people have gone unheard and been completely disrespected by the process,” Stewart said. “It almost tells you that elections don’t even matter, which is insane. It should matter who your representative is in the Legislature.”

The conservative-leaning Maine Policy Institute ranked the state 22nd — the middle of the pack — for the balance of powers between the executive and legislative branches in emergencies. The think tank created a scorecard to measure the states’ legislative checks on executive branch powers. States with more legislative oversight were ranked higher.

In some instances the group provided sample language or consulted with Maine lawmakers on ways to craft legislation to modify the emergency powers, said Jacob Posik, director of communications. Maine’s law does not allow legislators to oppose or support specific actions the governor makes in an emergency, rather lawmakers can only vote to end the emergency. It also does not guarantee an expedited review of any court challenges to the orders.

“You can’t show up and have any say in what is going on related to the virus and I think that flies in the face of why emergency laws exist,” Posik said.

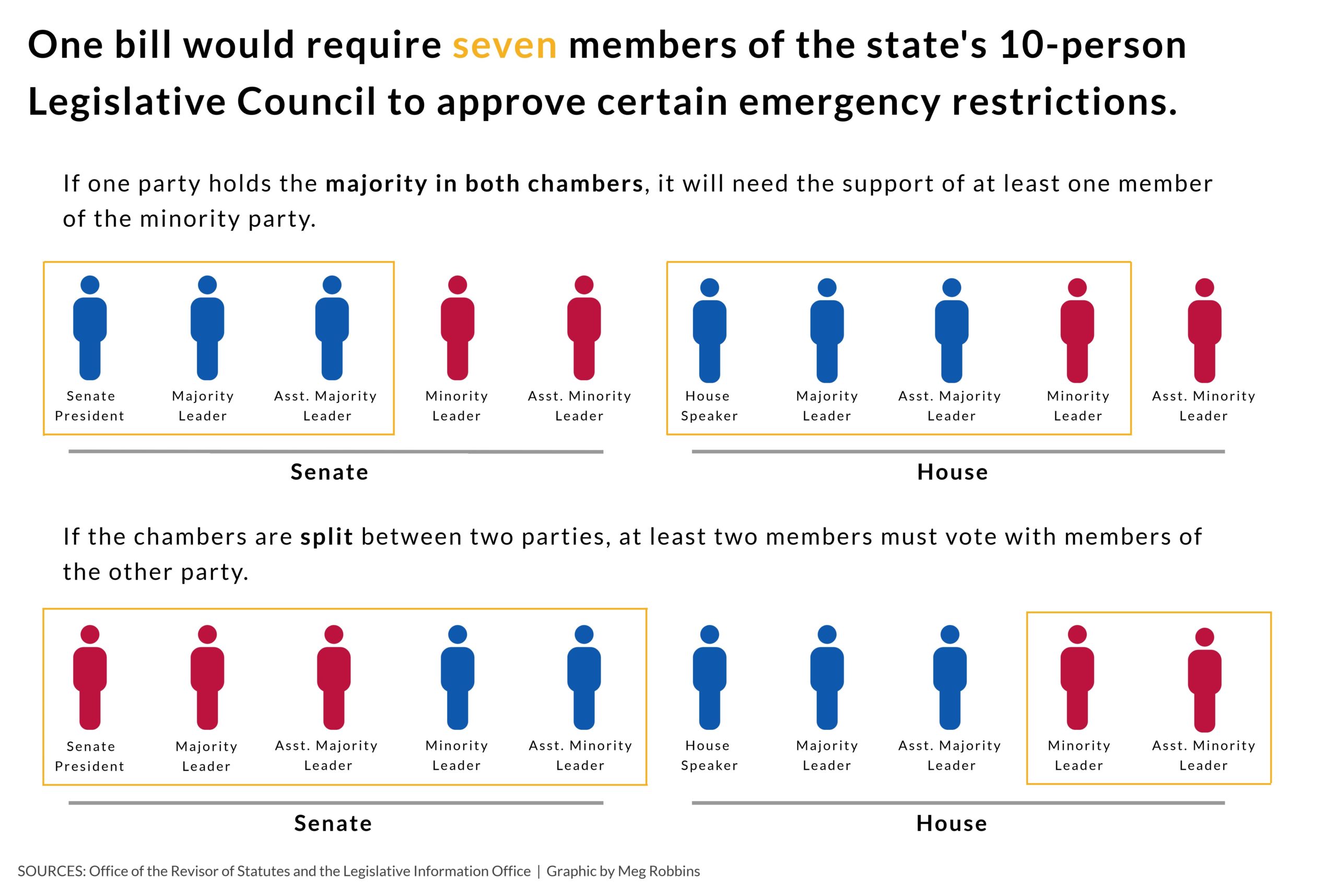

Some proposed legislation would give new authority to the Legislative Council, a 10-person board that manages the Legislature and is composed of the highest-ranking lawmakers from both parties.

Democrats control the House and Senate, and have six seats on the council. At least one bill would require a two-thirds vote of the council — equal to seven members — to approve restrictions during a state of emergency. Meaning even if one party controlled both chambers and the executive branch, the minority party could block an emergency order.

Minority Leader Dillingham has proposed language to add the approval of the Legislative Council for the governor to declare certain restrictions during a state of emergency. Her role on the council would give her crucial votes on whether the governor could limit business, restrict religious organizations or even apply the emergency order statewide.

Her bill is not intended to restrict Mills, but to ensure future governors communicate with the Legislature during an emergency, she said. Dillingham said for that reason she intentionally drafted it so it would not be enacted until at least September if passed by the Legislature.

“I fear that this will certainly be treated as an attack on Gov. Mills,” Dillingham said. “I’ve been there a long time and it’s personal to me in that I admire the way that our government is supposed to work. And when it works the way it’s supposed to, it works well.”

Democrat control of the legislative and executive branches make it unlikely that any of the proposed bills will become law.

Rep. Ann Higgins Matlack (D-St. George) would not speculate about the bills’ chances in the State and Local Government Committee she chairs. She cautioned it may be premature for lawmakers to look at the current use of emergency powers while a public health crisis is ongoing.

“Having these bills may not necessarily be a bad thing,” Matlack said. “But I think once we are totally through this — once people have been vaccinated, once this is not hanging over our heads as ominously as it is right now — that would be an opportunity to review the executive powers.”

Anticipating the next emergency

Changing the executive powers while the pandemic is ongoing could have the unintended consequence of hindering a future governor during the next emergency.

Most lawmakers agree emergency powers are necessary to respond to natural disasters and there is “immense” political pressure to support emergency declarations in those situations, said Price, the law professor. Where lawmakers disagree is whether governors should be able to impose public health measures, such as mask mandates and gathering limits, without consulting the Legislature.

“You just want to be careful not to hamstring the governor in what are really legitimate powers that they’ve had for a long time,” Price said.

Critics of Mills’ extended state of emergency say the emergency powers are not designed for pandemics. But one of the longest emergency proclamations in Maine lasted 89 days under Baldacci in response to the H1N1 influenza pandemic — more commonly known as the swine flu.

Baldacci announced a civil state of emergency on Sept. 1, 2009, to allow the planning for mass vaccination of residents against influenza at schools and clinics. He extended it twice before it ended in late November 2009.

The 2009 swine flu pandemic killed 12,000 people across the United States, including 21 Mainers, and locally put 250 people in hospitals.

Maine ranked among the top states for swine flu vaccination rates across all population groups with 51 percent of the priority groups getting a shot, the Department of Health and Human Services reported in a self-assessment a year later.

LePage has disagreed strongly with Mills’ use of emergency powers throughout the pandemic. He disparaged her broad use of quarantine orders on healthy people. He said he would have coordinated closer with local emergency management to control “hot spots” of COVID-19, such as the one associated with a wedding in Millinocket that was connected with eight deaths.

LePage said he agreed with the national response to the pandemic in early 2020, but criticized Mills and other Democrat governors for later using the emergency for what he characterized as a way to gain power and control.

“Emergency powers are very short term, like a major snow storm, a flood, things like power outages. That kind of stuff,” LePage said. “Anything a lot longer than that, like this pandemic issue, I don’t consider that emergency powers.”

Officials with the Mills administration said LePage did not appear to have a clear understanding of the science of COVID-19, and chastised cuts he made while governor to the Department of Health and Human Services and Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

“COVID-19 is a substantial threat in part because it can be, and often is, transmitted by asymptomatic individuals – meaning those who are carrying the virus but appear healthy – and it is transmitted by individuals before they become symptomatic, meaning when they appear healthy,” said Crete, press secretary for Mills.

Mainers are confronting an emergency that has proven far more deadly than the storms and power outages they’ve previously weathered. And many experts warn this virus may not be the last we see in our lifetimes.

Dr. Nirav Shah, director of the Maine CDC, said the emergency declarations are “critical” to the agency’s response during a pandemic, including future public health crises.

“Without having the flexibility afforded by some of these declarations, as well as perhaps the ability to bring on more materials through procurement, if we weren’t able to move that quickly, that nimbly … that could slow our response down,” Shah said.

Mills’ proclamations have allowed the CDC to maintain its pandemic response, said agency spokesman Robert Long.

Without the state of emergency, he said, the public health and safety measures in place also would end.