As part of an independent school project, Lillian Sherburne decided to have her school’s drinking water tested in 2017. She was driven, in part, by the water crisis in Flint, Mich., where elevated levels of lead were found in water supplies.

Then a junior at Boothbay Region High School, Sherburne approached the school’s facilities director, David Benner, and he agreed to coordinate with the superintendent to take on testing to be sure the school’s water was safe to drink.

Lead consumption, including in drinking water, has been linked to wide-ranging health problems such as decreased IQ, impaired nerve function and increased risk of hypertension in adulthood. And children are more susceptible to these risks than adults: A 2010 World Health Organization report notes that children can absorb up to half the lead they ingest, compared to just 10 percent in adults.

“I think water is a fundamental human right,” says Sherburne, now finishing her freshman year at Simmons University in Boston. “It’s vital to human function. It’s vital to functional education. So making sure that my classmates and I had access to good water was important to me.”

Results of the testing stunned her: Levels of lead at a magnitude higher than the concentration deemed safe by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency were found at classroom drinking fountains and faucets within the high school and elementary school.

“I was shocked,” says Sherburne.

As a precaution, school administrators posted “Do Not Drink” signs at all water fountains and shut off cold water lines to prevent consumption until they got a better handle on the problem. They set up more than 30 portable water stations in the two schools and consulted with an engineering firm about next steps.

“I was as concerned as everyone else was, for obvious reasons,” says Benner, who coordinated a mitigation plan.

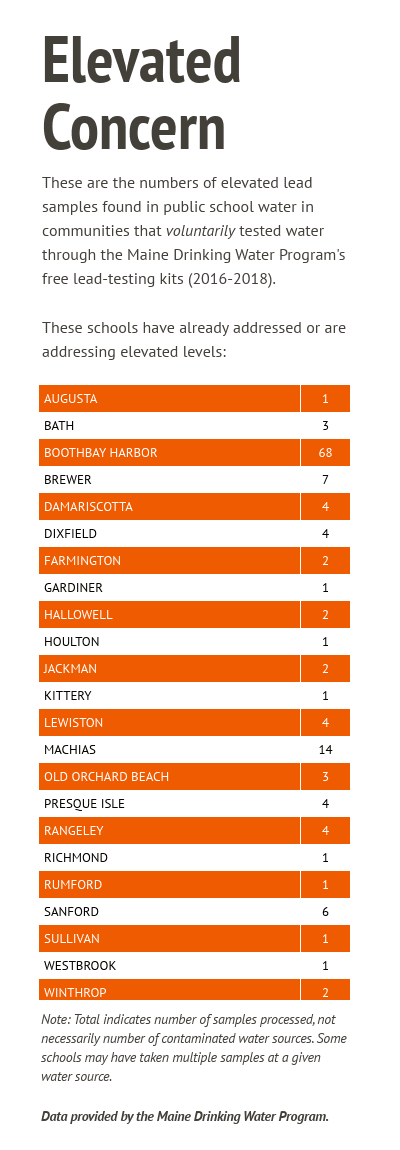

Boothbay is one of dozens of Maine school districts to discover elevated levels of lead in drinking water in recent years, according to test results Pine Tree Watch gathered from the Maine Department of Health and Human Service’s Drinking Water Program.

In all of these cases, school officials only discovered lead problems by voluntarily testing for it. Maine does not require public schools to test water for lead if they’re connected to public water supplies because those suppliers already conduct regular quality tests.

But in the case of Boothbay and other schools that have found elevated levels of lead – including Machias, Lewiston, Rangeley and elsewhere – the source of contamination hasn’t been from the water itself, but rather from the plumbing in older school buildings, where lead can leach out of solder joints.

That means that more of the roughly 500 public schools in Maine on public water could have dangerously high levels of this harmful neurotoxin, not know it and have no legal obligation to test for it.

A bill, LD 153, proposed by state Sen. Rebecca Millett (D-Cape Elizabeth) would change that by requiring all Maine schools to test for lead. While her efforts have received wide support, some opponents of the bill’s original language argued that it would be an unfunded mandate that could financially stress schools that don’t have funds to cover mitigation costs. In response, Millett amended her bill so that schools would need to check for lead but not be required to mitigate problems.

“It’s important that folks know whether there is a problem or not,” says Millett. “My view is, because of the serious nature of lead, if they were to find that there was an issue, they will take whatever action is necessary.”

What does mitigation involve and cost?

To gauge the financial burden such mitigation projects could place on schools, Pine Tree Watch spoke with staff members from five schools that already have tested, found and treated lead in their drinking water. The extent of testing varied across schools, with some covering a higher percentage of fountains and faucets in their buildings than others. Remediation costs in these five cases ranged from close to $100,000 for Boothbay to less than $1,000 or no costs at all for others that were able to simply stop using contaminated faucets.

Millett’s bill would not impact the majority of Maine schools operating with budgets less than $1 million (according to 2017-2018 DOE list of school budgets and DHHS list of school districts on public water) since those schools predominantly use private wells and already are required to routinely test their water.

“We know that no level of lead is safe for our children and that exposure to lead can lead to impaired development, especially for developing brains,” Millett said during the bill’s public hearing in February.

Victoria Wallack, communications and government affairs director for the Maine School Management Association, supported Millett’s bill at that hearing: “School leaders support water testing in school because it is our responsibility and commitment to keep students safe and healthy.” Still, Wallack noted, some schools may struggle to come up with mitigation funds to deal with problems that become apparent from more widespread testing. “One concern we have had from the start is how districts will pay for mitigation.”

The Department of Education’s School Revolving Renovation Fund ultimately could help support mitigation costs, and funds already exist to assist with preliminary lead testing through the Drinking Water Program.

This program offers schools up to 10 free lead-testing kits that otherwise would cost about $20 each, notes program Director Mike Abbott. Funding for these kits comes primarily from federal sources, says David Braley, a hydrogeologist with the program.

Since this free testing program launched in 2017, about 60 towns and cities in Maine have taken advantage of it, generating about 2,080 results. Of those communities, an alarming 24 have found at least one elevated lead level at or above the 15 ppb action level determined by the EPA.

Drinking Water Program staff members have helped advise schools with elevated levels about how to mitigate, says Braley. “We have gotten wonderful response,” he says, noting that these schools have all either resolved their problems or are in the process of doing so. “They were all appreciative of the opportunity to test, and the schools that found issues took steps to mitigate. They found a way to get things done.”

Of all the school districts that have reported results to the program, Boothbay had both the highest overall reading of 1,100 ppb from one classroom sink – more than 70 times higher than the EPA action level – and the highest overall number of elevated samples at 68 (though Benner also conducted more tests than other schools have, according to the database compiled by the Maine Drinking Water Program).

Of all the school districts that have reported results to the program, Boothbay had both the highest overall reading of 1,100 ppb from one classroom sink – more than 70 times higher than the EPA action level – and the highest overall number of elevated samples at 68 (though Benner also conducted more tests than other schools have, according to the database compiled by the Maine Drinking Water Program).

Efforts Benner has spearheaded to resolve these problems have included installing 11 new water fountains in hallways across the elementary and high school, replacing fixtures on classroom fountains and faucets throughout the buildings and replacing other plumbing components. Benner also instituted a policy that requires teachers to flush their classroom faucets for three minutes every morning, since lead is more likely to accumulate in water that sits stagnant within pipes for extended periods of time.

By the end of the last stage of plumbing renovations this summer, Benner estimates these efforts will cost a total of about $100,000, and that he has spent at least 300 hours working to resolve the issue. But while the time and resources required to fix the problems haven’t been trivial, he says the school district was able to incorporate the costs into its roughly $10 million budget. “We thought it was the right thing to do,” he says. “Nobody questioned anything that we spent.”

Eliminating lead issues isn’t always a costly proposition

The cost of lead-mitigation repairs has been far lower in other schools.

Alan Kochis, the Bangor School Department’s director of business services, reports that the district spent roughly $46,000 on testing and mitigation efforts in 2016, before the Drinking Water Program had started offering free testing kits. Testing was conducted at that time out of concern with the crisis in Flint.

Kochis says he’s not generally in favor of imposing sweeping mandates on schools across the state, but he does think it’s a good idea for schools to check for lead – especially those with older buildings. As for the costs of mitigation, $46,000 came from the budget for Bangor schools, but those costs may be prohibitive for other smaller schools, he notes.

“You have to put it all in perspective in terms of the size of the budget,” he says.

Costs of repairs may be far lower in smaller schools with smaller budgets since those schools likely have fewer faucets to test and fix than larger schools, notes Lindsey Savage, the nurse at the roughly 200-student Rangeley Lakes Regional School. She coordinated lead testing for her school, where two sinks were found to have elevated levels. One sink had already been slated to be removed during upcoming renovations, and the other – which students don’t have access to – was only used by staff to wash hands.

“We didn’t have to go through and change any pipes or anything like that, so we were lucky in that regard,” Savage says.

Scott Porter, superintendent of the Machias Bay Area School System, says his district spent roughly $2,500 to replace fixtures and install filters to remedy problems he identified after conducting lead testing through the Drinking Water Program in 2016 and 2017. “It really wasn’t a very expensive situation for us,” he says, noting that most of the funds went toward replacing four water fountains.

Lewiston Public Schools found elevated levels of lead when Louie Turcotte, director of facilities at the time, conducted his round of free testing in 2017. He estimated that repairs amounted to less than $1,000, and involved replacing problematic drinking fountains and shutting down other unnecessary water lines. “They were all dealt with directly in-house – we were able to take care of it,” he says.

These examples indicate the range of solutions Maine schools may pursue as they figure out mitigation plans.

“There are other ways beside immediately calling the plumber, at least for the short term, to mitigate,” says Braley with the Drinking Water Program, noting that simply turning off contaminated water lines could be a way to resolve problems in the short term.

If Millett’s bill passes, Drinking Water Program officials would prioritize reaching the estimated 300 public schools on public water that haven’t taken advantage of their free tests yet — though some of those schools, like those in Bangor, have already conducted testing on their own. So the number of untested schools is likely lower than 300.

For example, Heather Perry, superintendent of the Gorham School District, says she was able to obtain free lead tests through the Portland Water District, which supplies their water. That meant she didn’t need the Drinking Water Program’s free service, and so her district isn’t included in its database. She didn’t find any elevated levels in her schools.

She adds that while writing a bill to fit all the diverse situations across Maine schools is challenging, all superintendents she has communicated with about the issue unanimously support testing water for lead.

“The safety of our students is paramount,” she says. “So we want to make sure what is in our drinking fountains and being consumed by our children is safe.”

With Millett’s amended bill approved by the Health and Human Services Committee, it’s now ready for the Senate floor.

Sherburne, who’s pursuing a bachelor’s degree in political science and a master’s in public policy at Simmons, hopes Millett’s bill passes. She says she’s glad that her school’s response has resulted in permanent change and hopes that other schools will jump on board with prompt testing as well.

“I think it’s really important to continue the momentum,” she says. “Not just in my high school but in all schools in Maine.”

When news first broke of the lead contamination in Boothbay schools in 2017, some parents expressed plans to have their children tested for lead poisoning. Benner says that none has since reported any results to him. He continues to test the water on a quarterly basis to make sure that renovations remain effective.

So far, he has found promising results. “We have lead readings so low you can’t even read them,” he says. “And that’s exactly where we want to be.”