More than $100 million was allocated to address Maine’s housing shortage and the ongoing homelessness crisis under budget measures passed by the Legislature last week.

The spending comes as cities and towns across the state grapple with maxed-out homeless shelters, unaffordable apartments and increasing numbers of people living on the streets.

“It’s really historic, I think,” Erik Jorgensen, MaineHousing’s senior director of government relations and communications, said Friday morning after the Legislature passed a supplemental budget that included the housing money the night before.

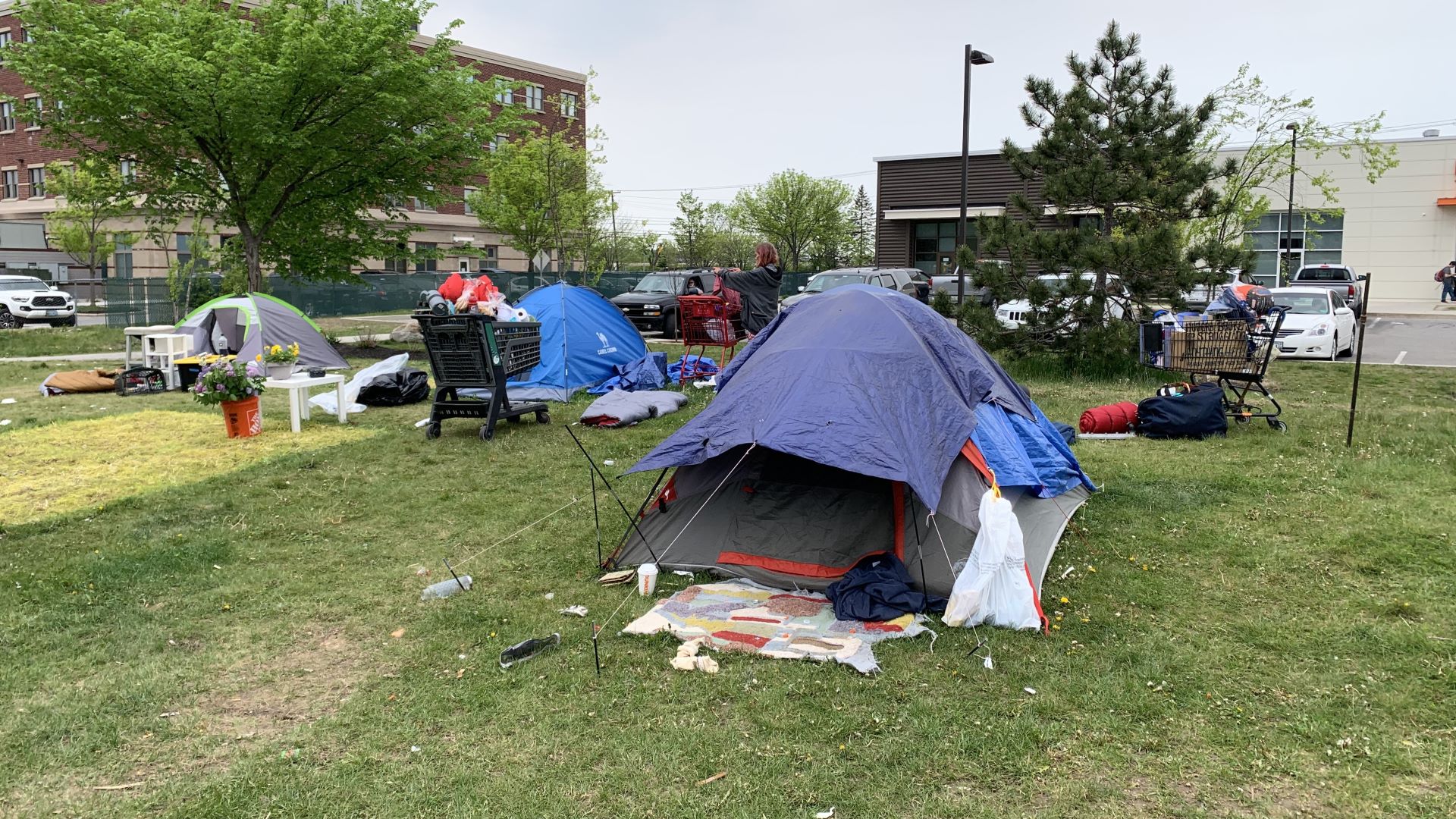

The crisis is most evident in cities like Portland, which continues to ponder how to handle the more than 1,000 asylum seekers who have arrived this year as well as the growing unsheltered population. In May, the city cleared a large homeless encampment along Bayside Trail. The individuals living in the 80 to 90 tents there said they had nowhere else to go.

With its family shelter and 208-Homeless Services Center at capacity, the city opened a 300-bed shelter in April at the Portland Expo specifically for asylum seekers. But the temporary shelter is set to close Aug. 16.

This latest funding follows an “unprecedented” infusion of about $43 million for emergency housing programs the Legislature approved over the winter, Jorgensen said.

Included in the supplemental budget passed Thursday is $70 million in one-time funding for housing subsidy programs statewide through the Rural Affordable Rental Housing Program and the federal Low-Income Housing Tax Credit Program. Both are administered by MaineHousing.

Gov. Janet Mills and MaineHousing launched the Rural Affordable Rental Housing Program in May 2022. The program, half initially funded by the COVID-era Maine Jobs and Recovery Plan, provides developers with subsidies and loans to construct affordable rental units in rural areas.

The program has approved seven projects that will add 115 units across the state, according to Maine Public. MaineHousing closed applications once the initial funding was exhausted and until more could be secured, according to its website.

The federal tax credit program is similar to the state one, providing subsidies for developers building affordable rental housing. A portion of the units must be reserved for lower income renters.

Maine is short some 20-25,000 affordable housing units, Cullen Ryan, the executive director of Community Housing of Maine, said in May. Fewer than 1,000 units are added to the housing stock every year.

“The last time we had an adequate supply of affordable housing was in 1977,” Ryan said.

The financial crisis of 2008, when “housing production was just disrupted everywhere,” has greatly contributed to the issue, Jorgensen said.

“The construction industry got so damaged at that point that it really hadn’t recovered. And then in a place like Maine you have additional issues of … aging construction workforce and … supply chain issues more recently.”

Those factors “conspired” to “make a real shortage of housing. That’s a real, real issue,” he said.

There can be any number of programs intended to help lift people out of homelessness, such as service navigators or job programs, but without affordable housing, “all bets are off,” said Shawn Yardley, chair of the Statewide Homeless Council.

The 14-member council serves as the advisory body on homelessness issues for the state, including the Legislature, Department of Health and Human Services, and MaineHousing.

“You’ve got to build more housing. So you’ve got to have subsidized housing because not everybody can afford the cost of living and what it costs to build something now,” Yardley said.

“Our system remains overwhelmed, and has not done a good job of getting people out of homelessness and into housing,” Ryan said late last month.

“And at the same time, our housing supply has dwindled and it’s hard to get people into housing,” he said. Emergency shelters are supposed to be a last resort, not the solution for homelessness.

“We may need to make adjustments with our shelters but for the most part, we need people to help people to get into housing and we need housing to be more available.”

The supplemental budget also included $15 million for the Low-Income Assistance Program, a “critical” program administered by the Public Utilities Commission and the Maine Public Advocate’s Office that helps low-income homeowners and renters reduce their utility bills, Jorgensen said.

The one-time additional funding will allow the program to temporarily expand eligibility to households whose income is slightly higher than the current limit of 75% of the federal poverty level, which is $30,000 a year for a family of four.

The budget also included $12 million for the continuation of short-term emergency housing initiatives that are currently in operation, according to MaineHousing.

There’s another $5 million in shelter operating subsidies, which Jorgensen said helps homeless shelters, nearly all run by private, nonprofit organizations.

“The pandemic has really caused a lot of pressure to go on to emergency shelters and the homeless system in general,” Jorgensen said. “So this is a really good thing to see.”

The budget also dedicates $1.5 million to a Rural Recovery Residence Fund to “provide one-time funds for the acquisition of land or real property to support the creation of certified recovery residences for families.”

The budget also launches the “Housing First” program, which prioritizes getting people into permanent housing first and foremost, and providing on-site and other community-based services.

The program is funded using real estate transfer taxes, not the general fund. Jorgensen said he expects funding will amount to about $10-12 million a year, with the first priority on building properties to house these programs. That may take a few years, MaineHousing Director Daniel Brennan told Maine Public.

The funding will “gradually transition” to supporting the services “necessary to make them work,” Jorgensen said.

Since the program is funded by a portion of real estate transfer taxes, it won’t be subject to future budget negotiations and cuts, Jorgensen said. The supplemental budget still must be signed by Mills, who has said she supports the bill.