The U.S. visa in Bereket Bairu’s passport could mean death or imprisonment if discovered at the wrong airport. It was also his ticket to freedom.

Bairu stretched a piece of chewing gum to seal the visa between two pages of the passport and slipped $200 inside as he handed it to a guard in his home country of Eritrea. He prayed — to a god he was not allowed to worship freely — that it would be enough to get him out of east Africa.

Like countless journalists, priests and draft evaders in the two decades since President Isaias Afwerki took power in Eritrea, Bairu risked “disappearing” into an underground prison or undisclosed grave instead of being allowed to board his plane to South Sudan. After a moment of hesitation, the guard pocketed the cash and waved Bairu to the gate.

Instead of feeling relief, anger and fear welled up inside him.

“I hated my country. I hated it because of the dictator,” said Bairu last month.

At age 49, Bairu has uprooted his life six times to escape imprisonment and persecution. He had been locked for two weeks in a shipping container, tortured for four months in political jail and sent to a year of forced military service. Each time he was unsure if he would survive. The longest period of uncertainty about his future, however, has been three years in Portland, where Bairu has waited for the U.S. government to decide whether he qualifies for asylum.

Every day asylum seekers across Maine wait for a phone call saying it is their turn to testify why they cannot return to their home countries and move into the next phase in the United States’ complex and overloaded immigration system. A national backlog of nearly 900,000 immigration court cases and 328,000 asylum cases sit ahead of them with new arrivals adding to the stack every day.

The arrival of more than 300 African migrants in Portland this June brought new attention to immigration to Maine. Bairu’s story is both unique and similar to the newest arrivals, but their journey from Africa, to Central America, the U.S.-Mexico border and finally, Maine, snaps into focus different flaws in the U.S. immigration system.

Bairu waited for 18 months in a virtual line of applications, then watched in dismay as the U.S. pivoted to prioritizing the review of the most recently filed asylum applications as part of a larger systematic crackdown on immigration in 2018 that has carried over into 2019.

“Two years I expected. I put (as the) time to hear my case but nothing happened, and the system changed,” Bairu said.

Abandoned in the middle of a stack of aging asylum applications, Bairu now finds himself at an impasse: He can try to expedite his application with the Boston asylum office, which granted asylum applications at one of the lowest rates in the country, a mere 12 percent, in 2018. Or, he can uproot his life for a seventh time, travel 3,000 miles and try to move his asylum claim to California where the odds of being granted asylum are more favorable.

As of March, there were 16,948 pending asylum cases in the Boston office, including Bairu’s. If he does nothing, he’ll remain stuck.

Systematic attack

Asylum is a legal status intended to protect people from having to return to a country where their life or freedom would be at risk, but it is also a legal protection that has come under constant attack by President Donald Trump’s administration, said Jennifer Bailey, the asylum program director at the Immigrant Legal Advocacy Project in Portland.

ILAP is Maine’s only comprehensive state-wide immigration legal service that represents low-income clients in complex immigration cases. At the end of June, its pro bono panel of lawyers was handling approximately 125 active asylum cases, which is a fraction of the total number of asylum cases that need lawyers in Maine.

Shifting federal policies and the highest rate of denial of asylum applications the last two decades has made finding a path to legal permanent residence for Maine asylum seekers that much harder.

“Since the Trump administration took over, there has been a systematic assault on asylees,” Bailey said.

There are two ways to apply for asylum in the U.S. People who are already legally in the U.S. on a visa, such as Bairu, can apply for asylum “affirmatively” with the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (CIS) within a year of entering the country. However, those who enter without documentation, like those who cross the U.S.-Mexico border, are placed in removal proceedings and must apply for asylum “defensively” in front of an immigration judge to stop deportation.

On both paths, in order to be granted asylum, individuals must show they suffered, or fear they will suffer, persecution in their home country due to their race, religion, nationality, political membership or membership to a social group. They must do this within one year of arriving in the U.S. on a form only printed in English and often without the help of a lawyer.

For a migrant who arrives at the border without a visa, entering the U.S. at a port of entry is one path to asylum, but it has also become increasingly difficult to do.

Border officials are limiting how many people may seek asylum and cross from Mexico into the U.S. each week under a policy called metering, which was used during President Barack Obama’s administration but has ramped up under Trump. Informal waitlists kept by migrants on the Mexico side of the border are more than a thousand names long, but border officials are calling about seven names a week, NPR reported on July 3.

On July 15, the Trump administration went a step further and announced it would no longer accept asylees from Central America at the U.S.-Mexico border who had not first applied for asylum in the next country they entered after leaving their home country, NPR reported. The order is being challenged in court.

Bailey said she found it “confounding” and “frustrating” that asylum seekers, who are the most desperate of migrants, are being vilified within a process that already makes it almost impossible to prevail.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection initiates deportation proceedings for all migrants who cross without a visa, but migrants who announce they want asylum at the port of entry are granted a “credible fear” interview with an asylum officer to explain why they would be tortured or persecuted if returned to their country. If there is a significant possibility the asylee could prove the claim in court, then they are protected from deportation. No credible fear interview occurs for those who cross between ports of entry.

Migrants are then either held in detention or granted parole to live in the U.S. while their case moves through immigration court. In a major shift in policy, Mexico agreed earlier this year to allow the U.S. to send those seeking asylum in the U.S. back to the Mexican side of the border while they wait for their cases to be heard.

Only one in five people seeking asylum in the United States complete their case within the first year, according to public data tracked by the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse at Syracuse University.

The outcome is also far from certain with immigration judges denying a record 65 percent of asylum cases in fiscal year 2018. In the last two decades, spanning President George W. Bush (R), Obama and Trump’s time in office, judges denied an average of 55 percent of asylum cases.

Unlike immigration court, the affirmative asylum pathway is not a formal judicial process for migrants who arrive in the U.S. with a visa, such as Bairu.

Affirmative asylum applications are distributed geographically between 10 asylum offices. All applications originating in Maine, New Hampshire, Massachusetts and Rhode Island are reviewed in Boston.

The Boston asylum office granted 12 percent of asylum applications in 2018, which is one of the lowest rates in the country. The majority of cases were referred to immigration court to start over as defensive asylum claims. Some were denied because the applicant did not show up, and far fewer were simply denied.

The demographic diversity and settlement patterns of U.S. CIS’s 10 asylum offices can lead to variations in approval rates, an agency spokesperson said by email.

He just stood out like a light bulb, and here we are in a prison with guards that shoot them if they escape. Yet, he stood out with a smile … that’s when we asked about his story and that he had been falsely accused and his persecution.”

— Carol Carlye, who helped Bereket Bairu navigate his way to the United States

“Asylum officers assess all cases on their individual merits and are informed by the law and country conditions associated with the particular claim being made. All cases receive 100 percent supervisory review,” said a CIS spokesperson.

The variation can be stark. Boston and New Orleans represent some of the smallest geographic jurisdictions, but where Boston granted 12 percent, New Orleans approved 56 percent of cases.

The low odds of being granted asylum in Boston are a concern to Bairu, who will have to go to immigration court if his asylum application is not approved. He is considering moving his asylum application to the San Francisco or Los Angeles asylum offices, which granted 42 and 33 percent, respectively, of asylum applications in 2018.

It’s unclear, however, if a change in venue will speed up the review of Bairu’s application. Asylum applications are confidential and cannot be discussed by U.S. CIS.

Like many migrants, Bairu could not afford legal assistance when he first filed his request for asylum three years ago. He would be navigating the U.S. legal process alone had it not been for Stephen and Carol Carlyle of Haverhill, MA., and Grace In God’s Hand Ministries.

Carol Carlyle met Bairu by chance in South Sudan in January 2015 while visiting the jail where he was being held as a political prisoner for the second time in his life.

“He just stood out like a light bulb, and here we are in a prison with guards that shoot them if they escape. Yet, he stood out with a smile … that’s when we asked about his story and that he had been falsely accused and his persecution,” she said.

Bairu surprised her two months later when he crossed into Uganda with an expired passport after being released from jail to attend the Bible school financed by the Carlyles. Then, he surprised the Carlyles again by finishing the classes in a year. The greatest shock, however, was when he called in June 2016 to say he was in America.

Bairu is the second person the Carlyles have helped apply for asylum in the U.S. The first was an Iraqi woman in 2008 who had two death fatwas — a legal pronouncement in Islam — against her. She was a Christian working in Jordan, and her permit was about to expire. To return home would mean death. Working with members of Congress, the Carlyles were able to get her to the U.S. in less than a year.

Their experience with Bairu has been different, and the delays have come as a surprise to even them.

During the three years Bairu has awaited an asylum decision in Portland, he has rebuilt the teaching career he left behind in Eritrea. Bairu tutors local high school and college students in algebra, geometry, calculus and statistics while also working nights as a financial auditor at the Westin Portland Harborview hotel, which is a short walk from the room he rents at the YMCA men’s dormitory.

He knows few Eritreans in the city, and he does not own a car so the families of his students will drive him between his tutoring locations, he said.

Bairu’s younger brother, Dr. Semere Bairu, is already a permanent resident of California and a lecturer at California State University, East Bay in the chemistry and biochemistry department. He was awarded a diversity visa and completed a Ph.D. in chemistry in the states. However, the Carlyles fear California is too far away to assist Bairu with his asylum cases and that he will lose the community and opportunities he has made in Portland.

Bairu fears what will happen to him and his family still trapped in Eritrea if he continues to wait.

Fleeing to freedom

Bairu spent his adult life avoiding mandatory and indefinite service to the Eritrea military.

Eritrea is a small country in east Africa that sits just north of Ethiopia and has a long coast abutting the Red Sea. Bairu grew up in the capital city of Asmara, where his father worked in an American soap factory and his mother sold vegetables in the local market. Despite a long guerrilla war against Ethiopia during Bairu’s childhood, he and his family lived in relative comfort and peace in the capital.

In 1991, when the country won its independence, Bairu was a young man headed to the University of Asmara, a government-run school, to study accounting.

Within two years of independence, however, President Afwerki announced all Eritreans must provide 18 months of “national service,” which is now understood to be involuntary conscription into the Eritrean military, according to Human Rights Watch. Suspecting as much, Bairu’s uncle warned him to avoid it.

Bairu withdrew from the university and hid as he waited to see what would happen to the people drafted into national service. The first four groups went and came back from national service, but the fifth group in 1998 — as Afwerki resumed a border conflict with Ethiopia — never returned to Asmara, Bairu said.

This did not bode well for Bairu, who had started a business to bring Ethiopian newspapers across the border to be distributed in Eritrea, which had a state-run media. He had 30 workers, who distributed more than 45,000 copies a week along with Eritrea newspapers, books and magazines.

Reporters Without Borders ranked Eritrea 178th out of 180 countries for press freedom in 2019, ahead of only North Korea and Turkmenistan.

One day, as Bairu sat in a café overseeing the distribution of papers, two young men in plain clothes approached. They asked for 50 copies of a magazine, which Bairu said he would bring to them. They instead told him to get into the car parked on the street.

They drove him to an office and asked him if he was the man distributing Ethiopian newspapers. He confirmed that he was. They then accused Bairu of giving information to the Ethiopian government. Bairu tried to explain that he was not, but an officer cut him off.

“Take him there,” the officer said.

They kept me for almost two weeks in a container. Until your morale breaks, your heart, you’re fed up (and) you lose your temper. It was the worst experience of my life in my country.”

— Bereket Bairu, an asylum seeker from the country of Eritrea

Bairu was loaded into a different car with four military men. They drove for 45 minutes to the entrance of a former U.S. military installation, which the Eritrean government converted into an underground prison known as “Track B.” Prison conditions and treatment of prisoners are poor in Eritrea, and there is a nearly non-existent judicial appeals process, according to a 2011 U.S. Department of State report.

“There were reports that prisoners were held in underground cells or in shipping containers with little or no ventilation in extreme temperatures. The shipping containers were reportedly not large enough to allow all of those incarcerated to lie down at the same time. Other prisoners were held in cement-lined underground bunkers with no ventilation,” according to the report.

Among those imprisoned and kept in life-threatening conditions were people evading national service, according to the state department.

The soldiers locked Bairu inside one of the metal shipping containers outside Track B, he said. He was let out at gunpoint to relieve himself in a field and told he would be shot if he ran, but he was otherwise left in the dark container for days.

“They kept me for almost two weeks in a container. Until your morale breaks, your heart, you’re fed up (and) you lose your temper,” Bairu said. “It was the worst experience of my life in my country.”

Then officials moved him to Adi Abeto — one of the most notorious and overcrowded prisons in Eritrea — where they began to torture him. Bairu said he was locked in a building without cells with 50 other men of different ages and ethnic backgrounds. Soldiers interrogated Bairu about his connection to Ethiopia and whipped him before asking the same questions over again. The guards would slap and bite the prisoners or chain their legs. Once, a guard pushed Bairu so hard from behind that he fell and cracked several of his teeth.

Bairu spent a month in the hospital and was returned to Adi Abeto prison. Three days later, a large van arrived and 20 prisoners were told to get in. Bairu had no idea where they were taking him next.

After a 15-hour drive, the soldiers forced the prisoners out of the van and told them they would now be providing agricultural labor for the government. They stayed there for three months before a car arrived and took them to a military camp, which already housed between 5,000 and 10,000 people, to begin their national service.

Bairu was forced to stay at the camp for a year, before he was able to return to his family for one week. He hurriedly filled out paperwork to finish his degree at the University of Asmara, so he could be close to his mother, wife and child again.

Bairu signed up for one class at a time and sometimes withdrew so that his final year at school stretched from 2002 to 2005. He was buying time in the hope he could stop himself from having to return to the military.

But the government and military were never too far behind. Soon he was assigned to a school for compulsory teaching under the guise of national service. Bairu pretended not to know of his assignment, and when people came searching for him, he bounced between the multiple businesses he had started.

Soon it became too dangerous to be in Asmara and in 2007 he fled and hid on a farm, which he transformed into a thriving red-chili business. In 2009, the government came and took all his workers and Bairu knew he was no longer safe even away from the city. He transferred all his money to his younger brother who had already escaped and took cash to pay smugglers.

Within 12 days, he crossed the border into Sudan to the sound of gunfire.

New beginnings, new challenges

Bairu’s eventual ticket to freedom was a U.S. visa, which is a luxury that sets him apart from the more than 300 migrants who fled political violence and arrived in Portland last month.

Africans received only 11.8 percent of immigration visas and five percent of non-immigration visas issued by the U.S. in fiscal year 2018, according to the U.S. Department of State. Without access to a visa, many of the 347 migrants who eventually arrived in Maine between June 9 and July 11 first had to fly to South and Central America and walk to the U.S.-Mexico border to request asylum before continuing another 2,100 miles to Portland where communities of African asylum seekers and refugees have formed.

Portland housed the sudden influx of migrant families in the Exposition Building downtown, but this was a temporary solution as the city is contractually obligated to return the venue to operation by Aug. 15. By mid July, the city had relocated seven of the approximately 70 families living in the center to long-term housing, said city spokeswoman Jessica Grondin.

Just a few weeks before, these families lived in tents or under tarps on the Mexican side of the border as guards allegedly blocked ports of entry into the U.S. where they could ask for asylum. One family, with a newborn baby, recalled fearing their child would drown as it poured rain and puddles formed where they slept as they waited, said Bailey of ILAP.

“When you’re fleeing for your life, you’re willing to risk your life,” Bailey said.

Many of the migrants who arrived in Portland in June crossed the Rio Grande River instead of entering at a Port of Entry. They were were met by U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents. ILAP found several migrants with paperwork from U.S. Customs and Border Protection that assigned them to immigration courts in San Francisco, Dallas and Chicago. Bailey said she had never before seen agents pick a random address and send people there.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection denied randomly assigning immigration court hearings by email on July 9.

“When processing individuals with a Notice to Appear who are released on their own recognizance … agents list the location of the nearest immigration court to where the individual claims he/she will be residing” and provide a change of address form, said Michael McCarthy, the Maine spokesman for border protection.

When Bailey asked one of the migrant women assigned to San Francisco immigration court if she knew where California was, the woman replied that she had no idea. This indicates she did not say she was going there.

The erroneous court assignments are a “big problem” for the migrants currently residing in Maine, because switching immigrations courts is not a straightforward process, Bailey said.

Asylum seekers assigned to a court other than Boston must wait for their case to be scheduled in the court on their paperwork before they can request to transfer. It can take several months to more than a year for a case to be assigned its initial hearing, Bailey said. At the same time, migrants face a one-year deadline to apply for asylum.

This is a problem because if migrants apply for asylum while their case is in another court, then their application can be placed on hold while the transfer is processed, Bailey said. The courts consider these “change to venue” requests to be a delay caused by the applicant, and the courts will stop counting the days that must pass before an asylum seeker can apply for permission to work.

The result is that asylum seekers with pending claims are not able to work for years, which affects their ability to support themselves and hire and pay for lawyers to represent them, Bailey said.

Most of the Maine-based migrants cases were still pending in late June, which means they were not yet among the 892,517 undecided cases on the U.S. immigration courts’ active docket up to April 2019, according to TRAC.

I need (a lawyer), but we don’t have money. We don’t work. We’re waiting for paperwork. How can you pay the lawyer?”

— Adolfo Luvumbua, a 42-year-old migrant living in Portland

Adolfo Luvumbua, 42, is among the migrants living in Portland waiting for his work permit. Luvumbua fled Angola with his four children and has lived in Portland for less than a year. He applied for asylum, but it is just the first step to securing the paperwork he needs to work and provide for his children. In June, he was waiting for a social security card so he could apply for a job.

Without a job he relies on financial aid from the state to pay rent and cannot afford to hire a lawyer to manage his family’s asylum applications.

“I need (a lawyer), but we don’t have money. We don’t work. We’re waiting for paperwork. How can you pay the lawyer?” Luvumbua said.

Cost is something state and city officials have struggled to balance since the migrants began arriving on June 9.

Gov. Janet Mills’ administration undertook a review of the state’s existing General Assistance Program rules and announced on July 18 it would expand services to asylum seekers to align with the state’s legislature’s intent in 2015 to expand housing, medical and food vouchers to those “pursuing a lawful process to apply for immigration relief.”

Mills, a first-term Democrat, also requested federal aid for Maine municipalities from the Federal Emergency Management Agency to recoup the cost of providing services to the influx of new arrivals.

More than $815,000 has been donated to the city of Portland since early June to help house and provide services to the influx of asylum seekers arriving from the border. The City Council is expected to discuss how to spend the money at its August meeting, and city staff have already begun to spend the $200,000 budgeted for the Portland Community Support Fund. City spokeswoman Grondin said she expected staff to request a portion of the donated money be sent to the city to recoup the costs of operating the 24-hour shelter at the Expo.

Nonprofits have also stepped up to lessen the burden on the city. The United Way of Greater Portland vetted more than 300 volunteers in June to help at the Expo.

The YMCA’s New American Welcome Center also offers English conversation classes for new arrivals to learn customs and the language skills needed to restart the careers as engineers, bankers and teachers that they left in their home countries, said Sarah Leighton, chief development officer for the YMCA of Southern Maine.

“I have never heard someone say they came to the U.S. because they wanted to. They’re forced to leave,” Leighton said. “They’re our neighbors now, and we owe it (to) them now to start their lives here.”

‘Our hope is that he stays’

To be granted asylum is to be awarded the assurity that one can stay.

The current bottleneck in U.S. immigration court is delaying that assurance for many migrants in Maine, who want to start careers, provide for their families and establish permanent residence. The delays also hurt businesses in Maine who see migrants as a source of skilled labor for the state’s aging workforce.

“We who were born and raised in Maine sometimes make fun of ‘people from away,’ while we complain that our state is getting older and that it is increasingly difficult to do business here. Let’s put an end to the complaints, put aside the politics, and do the logical thing – welcome a workforce that is right on our doorstep and put them on the path to employment to build and strengthen our economy,” Mills wrote in an op-ed published by the Portland Press Herald.

The Portland Public Schools system is among employers looking to hire from the pool of newly arrived immigrants.

While the school system has the most diverse student body in the state, 92.5 percent of its staff in the fall of 2018 was white. Asylum seekers and refugees who were teachers are among the candidates Portland schools hopes to attract as part of its effort to diversify its staff, said Barbara Stoddard, coordinator of talent development at Portland Public Schools.

However, each asylum seeker and refugee faces a unique set of challenges to becoming certified to teach in Maine. That could include the financial cost of acquiring and translating their college transcript, developing or demonstrating English proficiency or — in Bairu’s case — resolving a note at the bottom of his transcript stating that no degree was awarded because he failed to complete his national service.

Knowing what national service really means, Stoddard wrote a letter on Bairu’s behalf to the Maine Department of Education asking that it grant him a conditional certificate to teach in Portland.

We believe what we believe: That this is the best thing for our students and when you speak to Bereket and (see) his grit and perseverance … our hope is that he stays and we have a position for him.”

— Barbara Stoddard, coordinator of talent development at Portland Public Schools

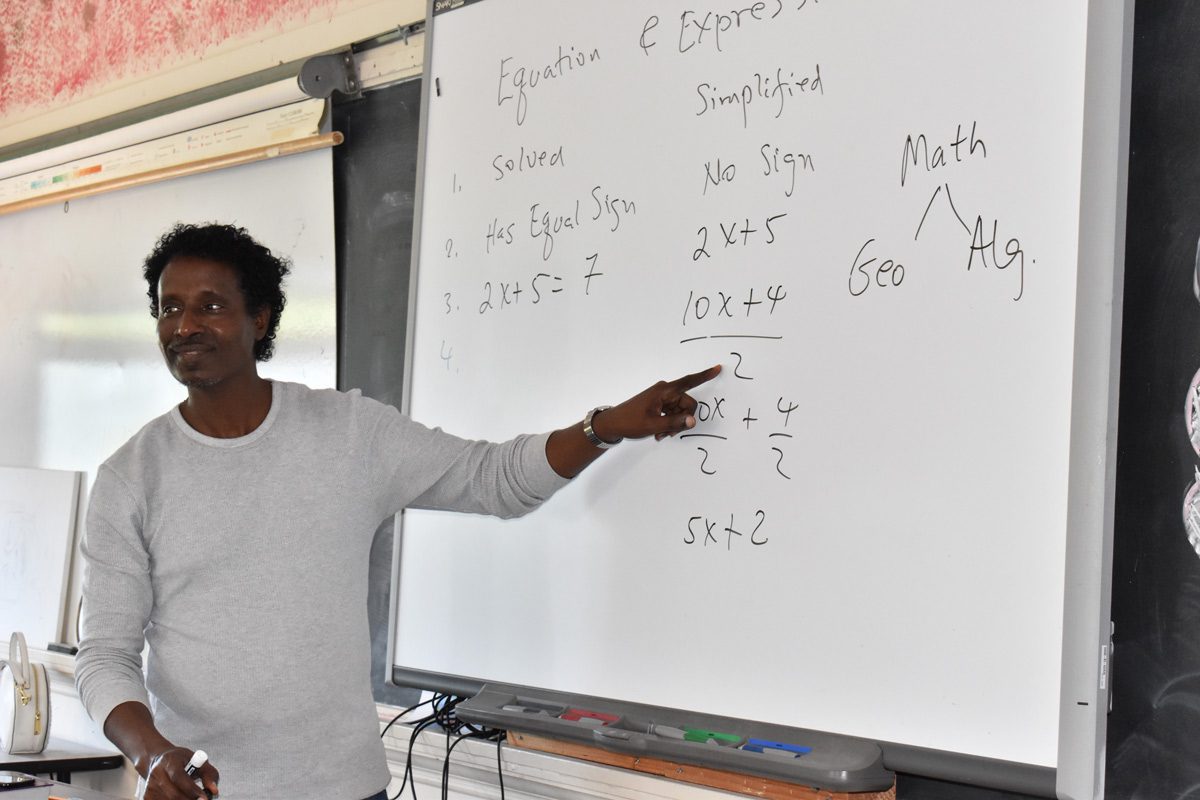

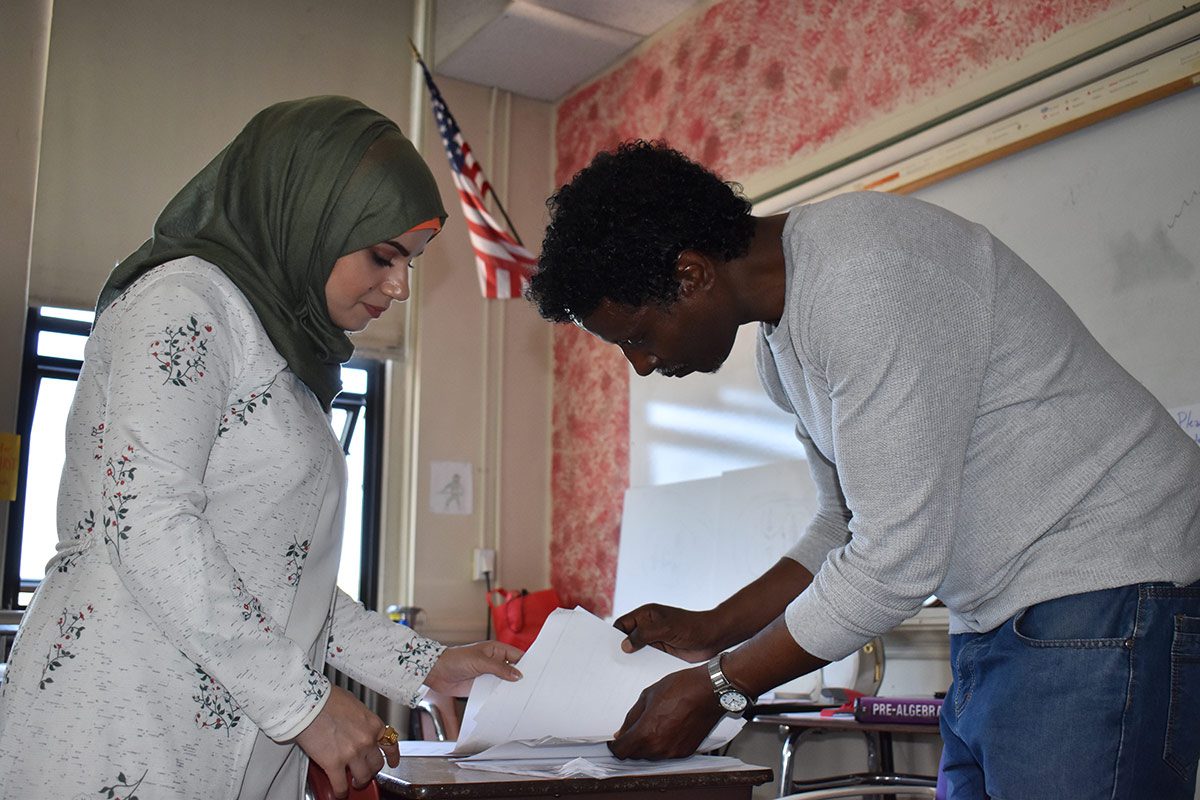

On July 8, Bairu stood in front of a classroom of Algebra I students in a summer course at Deering High School and led them through a lesson on the difference between equations and expressions. He was joined by his teaching aide, Tabarek Aldarraji, a 24-year-old Iraqi immigrant and civil engineer, who will start as a substitute math teacher for the school system in the fall.

Portland Public Schools needs qualified math teachers, and Bairu has proven to be a strong candidate, Stoddard said. Never has his status as an asylum seeker been considered during the process of getting him certified and on a path to teaching, she said.

“We believe what we believe: That this is the best thing for our students and when you speak to Bereket and (see) his grit and perseverance … our hope is that he stays and we have a position for him,” Stoddard said.

But, every month Bairu does not have an answer to his asylum application is agony to him and his family.

His eldest son is now 22 and deferred national service to study at the country’s one university, but eventually he will be required to serve. His 15-year-old daughter dreams of becoming a doctor, which Bairu knows will not be possible if she remains in Eritrea. He calls her weekly, despite the cost, to talk to her about school.

Bairu has already missed 10 years of being able to parent his children, and his wait in the U.S. has only stolen more time.

For the first time in his life, Bairu wants a government to acknowledge he exists. He needs an answer to know if his sixth new beginning is his last. He needs to know if he can stay.