Growing concerns about how well Maine’s nine public charter schools are educating students have some predicting that legislation to shut down charter schools will be on the docket next session.

Maine’s Democratic lawmakers succeeded where no other state did this year in passing bills to limit charter schools. It’s a sign that there may be political will to go a step further and begin closing charter schools next year, said Todd Ziebarth, a state advocate with the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools.

Top politicians on the joint Education and Cultural Affairs Committee say the intent of changing the law this year was only to “pause” and “review” the performance of Maine’s charter schools. Appointees to the Maine Charter School Commission, however, cited a year-end deadline to have a closure policy as one of their motivations for approving an “intervention protocol” to identify deficient charter schools on Aug. 6.

RELATED: Maine’s charter schools shake up entrenched learning systems and see results.

Rep. Michael Brennan (D-Portland), who staunchly opposes charter schools and was the lead sponsor on the bills limiting them this session, also ominously referred to the protocol as a “decertifying” document in an interview with Pine Tree Watch the day prior.

“I don’t think that we ever felt, up until now, that we were at a point that we would even consider closing a charter school,” said Jana Lapoint, a founding member of the Maine Charter School Commission.

A sense that charter schools are under attack, however, is something she’s felt for a while.

I don’t think that we ever felt, up until now, that we were at a point that we would even consider closing a charter school.”

— Jana Lapoint, a founding member of the Maine Charter School Commission

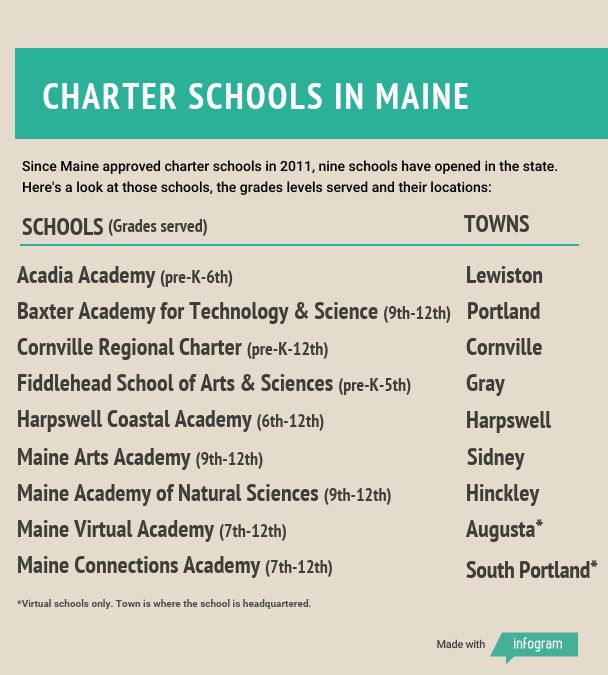

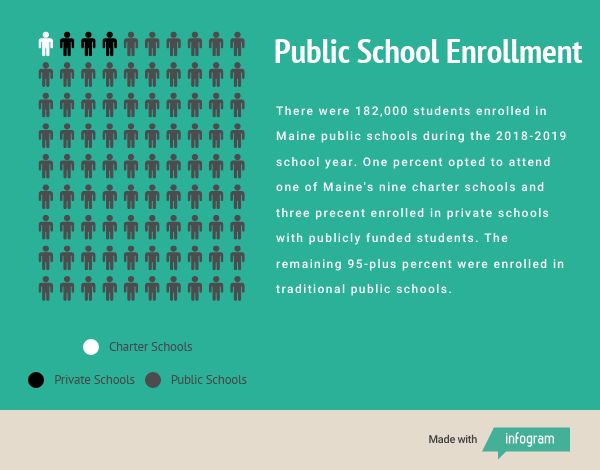

Approximately one percent of Maine’s 182,000 public school students are enrolled in public charter schools.

Why a limited number of students and schools have caused such an oversized uproar finds its answers beyond Maine. A national schism between Democrats and Republicans on public K-12 education underpins the controversy, which saw renewed attention following the election of a “blue wave” of Democratic politicians in 2018, including in Maine’s house, senate and governor’s office.

In preparation for next year’s debate, the Maine Department of Education is gathering bids from research companies to study the effects of charter schools on the public education system, with a report due by Dec. 1. Maine’s top education policy maker, Commissioner Pender Makin, says she’s waiting for the study before forming her opinion

Members of the Maine Charter School Commission, however, are already voicing skepticism that the findings will be taken seriously if the report is favorable to charter schools, and some lawmakers are giving credence to those fears by saying there’s too much evidence against some charter schools to let them stay open.

‘Close and replace’

Rep. Tori Kornfield (D-Bangor), a public school teacher for 37 years and current co-chair of the Education and Cultural Affairs Committee, said charter schools shouldn’t remain open if they can’t perform as well as or better than the surrounding district schools.

“If they’re not going to be better than, then why have them?” Kornfield asked rhetorically.

Maine public charter schools are mandated, by law, to, “improve pupil learning by creating more high-quality schools with high standards for pupil performance.” They must also close achievement gaps and provide alternative learning environments for students who are not thriving in traditional school settings.

Maine public charter schools are mandated, by law, to, “improve pupil learning by creating more high-quality schools with high standards for pupil performance.” They must also close achievement gaps and provide alternative learning environments for students who are not thriving in traditional school settings.

What defines a “high quality” school, however, is up for debate.

On paper, the Maine Academy of Natural Sciences in Hinckley is not a top performing school. Only 30 percent of the charter school students read and write at, or above, grade level, and 69 percent graduate in four years, according to state data from the 2017-2018 school year, the latest available.

Deep into summer vacation for most schools, students at the Maine Academy of Natural Sciences were in their last week of classes on July 31. A group of three young men gathered around a snowmobile engine outside the campus greenhouses while Patience Goulette, 14, checked the progress on a bee enclosure she designed for the school’s 1-acre farm. It was a typical day at the school, which offers a self-paced curriculum for students who often struggle sitting in a traditional classroom.

Danni Best, who recently took over as head of school, knew she needed the job as soon as she met the students. Some were close to dropping out before they arrived at the charter school, while others, like Goulette, were homeschooled and looking for a place to complete high school without being restricted to a desk and classroom.

The school graduated 36 teenagers this year, many of whom said in their Senior Night speeches that they would not have finished high school if they had been forced to stay at the schools in their home districts. Some were headed to college, while others had jobs lined up in professional trades.

Where Maine Academy of Natural Sciences students struggle is on test day.

“It’s very hard to do testing here. It’s just painful, because of the kids,” Best said. “They just freeze and freak.”

All charter school students are tested in the fall and spring on the Northwest Evaluation Association (NWEA) test, which allows the school to map individual academic growth during a school year. Third through eighth graders are also tested annually on English and math on the Maine Educational Assessment state exam, while eleventh graders take the SAT, which the Maine Department of Education collects and reports publicly.

Politicians and charter school leaders agree that not all students learn the same way and fostering different classroom environments at charter schools helps some students. They diverge, however, in their opinions of whether test scores should be the best marker of a student and school’s academic success.

Kornfield has served as chair of the committee for the last five years and will reach her term limit in the state House of Representatives at the end of 2020. She said legislators are increasingly unimpressed with the academic performance of some charter schools, and that led to the bills passed this session to limit them.

The data from the 2017-2018 school year presented “damning” evidence against some of the charter schools, with test scores too low, reports of absenteeism too high and too few graduates to justify remaining open, Kornfield said.

Kornfield said she would not seek to close all charter schools due to the poor performance of a few, but rather close and replace those that continue to not show improvement, she said.

The ripple effect on children, families, communities and the public education system if a charter school did close, however, is what Makin is waiting for the study to weigh in on.

Makin is no novice to public charter school education. She was a board member for the Maine Academy for Natural Sciences when it opened in 2012, and she testified in support of the enabling legislation for charter schools in 2011 because of its emphasis on drop-out prevention and innovation.

She was also the principal of the Regional Education Alternative Learning (REAL) school from 2003 to 2015 on Mackworth Island in Falmouth, which provided alternative education for students with extreme social, emotional or behavioral problems that made it no longer feasible for them to be taught in their home districts.

“We recognized that all kids — whether they had disabilities or not, or diagnosed or not — all kids, and really all people, need some of the same very basic things before they’re going to be successful. So feeling safe, for example, physically and emotionally. Feeling connected and important, and feeling like they’re a part of something,” Makin said.

A feeling of safety and belonging is something many children who enroll in charter schools lack at their home district schools. Pine Tree Watch interviewed executive directors, principals and teachers at six of the nine public charter schools, and each said fostering community values, creating bonds between teachers and students and allowing students to feel safe were part of the school’s mission and set them apart from district schools.

As a result, the schools say they have seen behavior improvements, re-engagement with learning and a deeper understanding and proficiency among students, but to see these positive changes often requires visiting the school rather than reading a report.

Travis Works, executive director of Cornville Regional Charter School, said he invited every member of the Education and Cultural Affairs Committee to visit his school and speak with the students. None have yet come.

“It’s always a concern when things are politicized,” and the threat of a charter revocation is a burden for the children and families, Works said.

Calculating success

By law, public charter schools must improve pupil learning, but evaluating that fairly is not as straightforward as it seems.

The Maine Educational Assessment is the only common test used at all Maine schools, which creates an annual snapshot of student performance. Lawmakers have pointed to charter schools’ scores on the state test as a sign of academic weakness, while educators say the exams aren’t reflective of how their students are learning.

As a whole, students who opted to attend a charter school rather than their home school district did not perform better on the test, but the aggregate data do have caveats.

We would prefer to have 85 percent of all students in charter schools at grade level or higher — of course we would prefer to see that — but that’s also not realistic and it’s not the group of students that may be drawn to charter schools.”

— Laurie Pendleton, a curriculum development expert and member of the Maine Charter School Commission

Acadia Academy in Lewiston attracted 61 percent of its pre-kindergarten through fourth-grade students from Lewiston Public Schools, which operates six elementary schools.

In the 2017-2018 school year, Acadia Academy reported 21 percent of students performing at or above grade level in English language arts on the state exam. Four of the six Lewiston elementary schools reported a higher percentage of students performing at or above grade level, while the other two performed worse than Acadia Academy students on the exam.

The difference in academic performance varied by only a slim margin between some of the schools, which is significant because Acadia Academy — as with many charter schools — had a smaller student body than the other Lewiston schools, said Laurie Pendleton, a curriculum development expert and member of the Maine Charter School Commission.

In October 2017, Acadia Academy had 30 students enrolled in third grade, which is the grade level that state testing begins. That means as few as three kids could shift the school’s score by 10 percent.

Comparably, each of the six Lewiston elementary schools had anywhere from 190 to more than 360 students enrolled in third through sixth grades, who could be tested, which greatly reduces the effect of a few students’ performance on the school’s overall score.

“Believe me, we would prefer to have 85 percent of all students in charter schools at grade level or higher — of course we would prefer to see that — but that’s also not realistic and it’s not the group of students that may be drawn to charter schools,” Pendleton said.

And while Kornfield may want to compare the academic performance of charter schools to district schools, it runs counter to current state practices.

The Maine Department of Education does not compare performance markers between schools because it recognizes the differences in grade levels, the number of students who can be tested and past academic achievement of the schools’ students are so varied that it’s not an even comparison, said Janette Kirk, chief of learning systems at the department.

The department doesn’t even compare schools to the statewide averages — 50 percent in English language arts and 37 percent in math — that it releases annually, despite the numbers being widely cited in the media as benchmarks for school performance.

The Department of Education instead looks for growth within a school and compares that growth to the school’s own baseline student performance. However, significant changes to the state test in the past two decades limits this to the past few academic years.

Where Maine could improve is in creating a system to identify high-performing charter schools.

Within three to five years of a charter school’s opening, the Maine Charter School Commission should be able to see trends in the school’s academic and financial performance, said Veronica Brooks-Uy, the director of policy at the National Association of Charter School Authorizers.

The association recommends having a default closure mechanism for schools performing below expectations and benefits high-performing charter schools can earn by routinely exceeding expectations, such as eligibility to renew their contract or decreased reporting requirements.

Under Maine’s current charter school system, all schools are treated the same, including Baxter Academy for Technology and Science in Portland, which is consistently the top academically performing charter school on state tests.

More than 80 percent of Baxter high school students tested at or above grade level in English language arts and 45 percent at or above grade level in math in the 2017-2018 school year.

Harpswell Coastal Academy, which opened in the same year as Baxter, on the other hand reported only 5.7 percent of middle and high school students at or above grade level in math in the 2016-2017 school year and nearly 18 percent the following school year.

Harpswell Coastal Academy, which has campuses in Brunswick and Harpswell, spent the past two years building out its curriculum, in part, to address low test scores, said Head of School Scott Barksdale. However, the school’s philosophical priority remains “depth over breadth” of understanding, which is in opposition to standardized tests that expect kids to have basic proficiency across many topics, he said.

Because there is no differentiation between high- and low-performing charter schools, Baxter and Harpswell academies were both awarded renewals of their charter contracts by the Maine Charter School Commission in 2017. Baxter’s renewal was for 10 years and Harpswell’s for five years.

Kornfield questions how contract renewals could be approved when students’ performance indicators are that low at Harpswell Coastal Academy.

“They have a commission overseeing them that can commission or decommission them, and there has not been enough improvement in some of them,” for renewal, she said.

Missed student time

How a student scores in a test one day of the year is one indicator of success, but how many days a student receives instruction — or misses it — may be a far more informative metric.

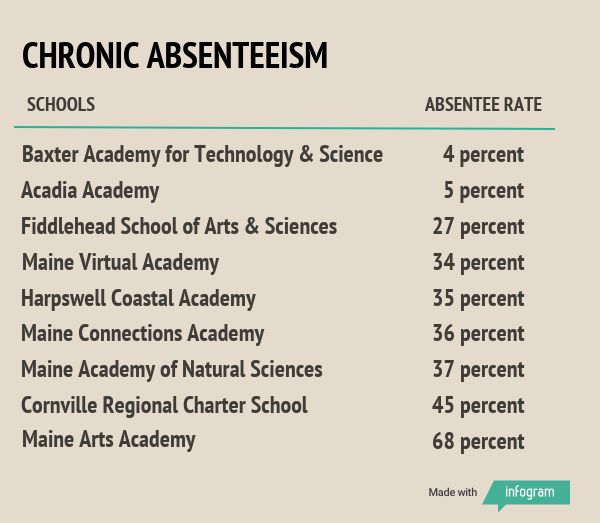

“Chronic absenteeism” is a new measure of school success that Maine started using in the 2016-2017 school year, and a number that lawmakers say is too high at charter schools.

A student is chronically absent when he or she misses 10 percent or more of the days they’re enrolled in school. The typical school calendar is 175 days long, so a student who misses 18 or more days — three weeks a year or more than two days in a month — for excused or unexcused reasons are chronically absent.

In the 2017-2018 school year, seven of the nine charter schools reported double digit rates of chronic absenteeism among their student populations.

The worst offender was the Maine Arts Academy in Sidney, which reported 68 percent of its students chronically absent. The school provides theater, vocal, instrumental and dance training in parallel with high school academics. Executive Director Deborah Emery and Principal Heather King disputed their students were as chronically absent as the data suggests.

The worst offender was the Maine Arts Academy in Sidney, which reported 68 percent of its students chronically absent. The school provides theater, vocal, instrumental and dance training in parallel with high school academics. Executive Director Deborah Emery and Principal Heather King disputed their students were as chronically absent as the data suggests.

A student is marked “absent” in Maine if they miss more than half of the school day, but the Department of Education leaves it up to each school to determine their own cutoff point.

Both administrators said several students who were dual enrolled in college courses at Colby College were marked absent from study hall when they were at the college or taking the course online. The error was not corrected with the Department of Education.

New tracking of chronic absenteeism, however, did allow the school to identify some students who were racking up unexcused absences. The school now calls parents and sends guidance counselors to make home visits to find out why students are missing school. This has helped improve attendance.

Maine Arts Academy also changed its schedule so that Fridays are full academic days, whereas, they were once a half day for teacher development and guest speakers for the students. They found students who were traveling a long distance to school would sometimes skip the half days on Fridays to cut down on travel time, King said.

Transportation is a unique barrier to attendance that nearly all charter schools face, said Bob Kautz, executive director of the Maine Charter School Commission.

“All the schools are facing it, because charter schools in Maine are required to be open for enrollment by a student who lives anywhere in the state,” Kautz said. “It’s up to the parent to get the child at least to the border of the catchment area, and then the school assumes responsibility to take them from there back to the school.”

Cornville Regional Charter School has difficulty getting parents to drive students to the bus stop or to campus in inclement weather, Works said. Even the threat of bad weather can result in a student staying home.

The school, which offers pre-kindergarten through 12th grade across three campuses in Cornville and Skowhegan, is working to educate parents on the importance of coming to school.

Transportation shouldn’t be a problem at Maine’s two virtual charter schools, yet more than one-third of students at both were chronically absent and did not log in for scheduled classes during the 2017-2018 school year.

The Maine Virtual Academy, which is headquartered in Augusta, hired a full-time staff member in December 2018 to monitor attendance and ensure students are logging on and participating in live classroom sessions, said Head of School Melinda Browne. The effect was clear with the school’s chronic absenteeism rate dropping to 11 percent in the 2018-2019 school year.

“Her entire job is monitoring the daily attendance report and reaching out to families and reeling those kids back in,” Browne said.

Preliminary data shows chronic absenteeism rates decreased at charter schools in the 2018-2019 school year, said Gina Post, director of program management for the Maine Charter School Commission. The rates are still being certified by the Department of Education.

One percent of students, two percent of costs

Brennan was quick to point out that his bills, now law, did not close any existing charter schools this year. Given the “sizable” amount spent by the state on the nine schools now, it was worth stopping and reviewing the cost, he said.

Brooks-Uy argues this is flawed logic that many states fall victim to in the belief that hitting “pause” will do more than directly addressing concerns.

“If that is the argument you’re going to make, let’s talk about the actual issues,” Brooks-Uy said.

Maine spent $25.8 million on public charter schools in fiscal year 2019, which ended on June 30. The spending represents just over one percent of Maine’s $2.2 billion total education budget and two percent of the state’s $1.1 billion contribution to education costs before teacher retirement.

Public education spending in Maine is set by formula, known as Essential Programs and Services (EPS), which charter school commissioner Jim Rier oversaw for several years as the director of finance and operations with the Maine Department of Education.

The EPS is intended to define the cost of programs and opportunities that all students need to have regardless of what school they attend, Rier said. Then, based on the appraised value of the community where the school is located, the Department of Education calculates how much of the EPS is the responsibility of the town’s taxpayers and how much the state will pay.

Affluent communities may be responsible for most of the cost of the EPS, while low-income communities may have up to 70 percent of their bill covered by the state. So while spending in every community will be different, the base amount of funding going to every school district should be equal.

Public charter schools are open to all Maine students regardless of zip code, and there is no community to base their EPS formula upon, so per-pupil spending is instead calculated for each students’ home school district and follows them to the charter school.

A common argument is that this “takes” money away from the student’s home district.

“I will always argue, the students aren’t there,” Rier said.

If the NEA looks at the money they’re losing from charter schools because the teachers do not have to be unionized, they don’t have to join a union if they don’t want to, they’re worried about their pocketbook. They’re not worried about if kids are learning.”

— Laurie Pendleton, a curriculum development expert and member of the Maine Charter School Commission

It also isn’t a one-to-one movement of money, Rier said. Baxter Academy for Technology and Sciences is budgeted for 57 Portland Public School students to attend in the 2019-2020 school year and bring $426,303 from their district, but it isn’t an equal loss for Portland, Rier said. Inflationary costs of teacher salaries, energy and fuel, and other costs offset it some, he said.

The model can create uncertainty for charter schools, too, Works said. The per-pupil spending that follows a child from Cornville Regional Charter School’s two largest feeder districts varies by almost $800 per child. If enrollment from the higher paying feeder district were to drop, state funding could decrease significantly while the cost of facilities, programs and teacher salaries remained the same.

Charter schools also do not qualify for state money to make capital improvements, so Cornville is financing the purchase and $2.6 million renovation to its high school in downtown Skowhegan with a 20-year commercial loan at 6.5 percent interest, Works said.

Charter school commissioners Lapoint and Pendleton, however, believe the ongoing rift between Democrtic and Republican lawmakers on charter schools is tied to a whole other source of money than the state budget.

The women blamed the state teachers’ union, the Maine Education Association (MEA), and its parent organization, the National Education Association (NEA), for tension over charter schools.

“If the NEA looks at the money they’re losing from charter schools because the teachers do not have to be unionized, they don’t have to join a union if they don’t want to, they’re worried about their pocketbook. They’re not worried about if kids are learning,” Pendleton said.

“This is simply false,” said MEA President Grace Leavitt, who is on leave from her job as a Spanish teacher with SAD 51.

The teachers’ union is a member-led and member-funded organization that does not rely on the National Education Association for money, she said. Its members also develop their own policy positions separate from the NEA.

“Students, not politics, are at the center of everything MEA members do and work for — and the Association believes all public schools should be held to the same standards with the same accountability, so our students receive an education that sets them on a path toward a great future,” Leavitt said.

Followers and leaders

If charter school closures are what’s next in Maine, then the Charter School Commission will have to decide whether its leading or fighting the decisions.

Sen. Dave Miramant, the sole Democratic member of the state Senate to break ranks and vote against the charter school bills this session, does not foresee the Democratic Party changing direction to support charter schools any time soon.

“I’ve never heard my Democratic colleagues supporting charter schools — maybe a few, but not as a party … It is not generally supported by the Democrats, and Democrats have the house, senate and governor’s office, and there’s not a great conversation about how to fix the ones (charter schools) we have,” Miramant said.

The political climate makes it easy to be pessimistic about the future of charter schools in Maine, said Ziebarth with the National Alliance of Public Charter Schools. He remains optimistic, however, because of the continued demand from families for quality charter schools in the state.

Politics also continuously evolve, he said.

I’ve never heard my Democratic colleagues supporting charter schools — maybe a few, but not as a party … It is not generally supported by the Democrats, and Democrats have the house, senate and governor’s office.”

— Sen. Dave Miramant (D-Knox County)

First-term Democratic Gov. Janet Mills did not sign the legislature’s bills limiting charter schools this session, despite campaigning against them during her run for office.

“The Governor does not disagree with the aim of the bills. She simply would have preferred, as the Department of Education testified, that an independent evaluation and review of Maine’s public charter school system be conducted to better understand how charter schools may affect the broader education system in order to help inform these decisions,” Lindsay Crete, a spokeswoman for Mills, said by email.

The study, annual charter school reports and input from additional boards will shape the statewide conversation on charter schools moving forward, Crete said.

And while legislators contemplate charter school closures, the Maine Charter School Commission may have to too.

“No one wants to close a school. It’s one of the hardest, most challenging, things an authorizer will do, but it’s part of their job,” Brooks-Uy said.