Maine leaders estimate that state courts won’t begin to address their backlog of cases until 2028, even with the anticipated hiring of four new judges.

The outlook is the best estimate available to the court from multiple studies, including one by the National Center for State Courts. The studies recommend approximately 10 new judicial officers to keep pace with cases being filed. Even those wouldn’t address the backlog, and the judicial branch hasn’t asked for that many.

“We’re being realistic,” said Chief Justice of the Maine Supreme Judicial Court Valerie Stanfill.

Gov. Janet Mills plans to include four judge positions in a budget change package, her spokesman Ben Goodman confirmed Wednesday.

“These new judges are in addition to the governor’s proposal for $15 million to allow the courts to hire additional marshals and clerks, which will enable the courts to operate more efficiently,” Goodman wrote in a statement.

Stanfill laid out the need for more judges, clerks, marshals and technology to effectively operate the state’s courts during a State of the Judiciary address Thursday to a joint session of the state Legislature.

Asked after her speech what the state of the judiciary is, Stanfill said: “The word I was thinking is ‘frail.’ “

“We’re there, we’re doing what we need to do, we’re working hard, but we’re being a little bit held together by duct tape and prayers at this point. It’s a little frail.”

Tina Nadeau, a criminal defense lawyer in Portland and executive director of the Maine Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, said adding four judges was not sufficient. Each additional judge could potentially do a few dozen trials a year, but that doesn’t make a dent in the thousands of additional misdemeanor and felony cases in the backlog, she said.

“Half-measures such as this don’t usually do a whole lot in the end,” said Nadeau.

Insufficient resources

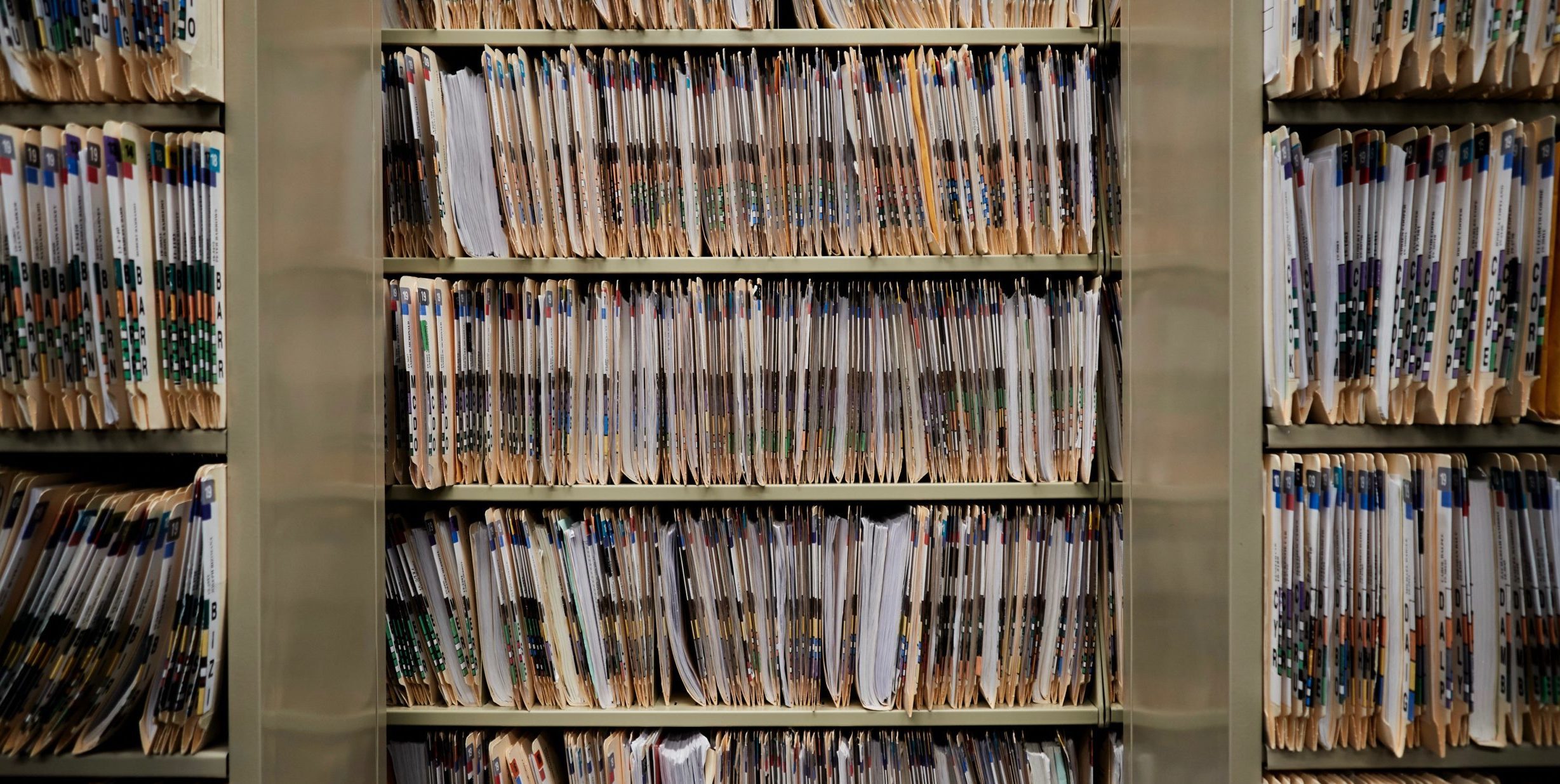

Maine has 63 judges across district, superior and supreme courts, according to the most recent report available. Governors and legislators have slowly added judge, clerk and marshal positions to address shortages over the past two decades.

Former Chief Justice Leigh Saufley said the need for more judges is a long-standing problem.

“What happens when you have something like COVID — and it affects a system where there are insufficient resources in several areas — is that the recovery becomes very difficult,” Saufley said. “Then you begin to understand, if you don’t have enough defense attorneys, you can’t move the cases forward. If you have enough judges but you don’t have marshals to get them in the courtroom safely, you can’t run the dockets. And of course we’re still dealing with issues around people feeling safe enough to come in and serve jury duty.”

“We call it the justice system, but we don’t often think about the reality that every aspect of the system can have an effect on other aspects,” Saufley added.

Saufley left the Maine Supreme Judicial Court in April 2020 to become dean of the University of Maine School of Law. Stanfill, appointed by Mills, was sworn in the following year.

Maine’s judges are consistently among the lowest paid in the country. Maine ranked 51st in judicial compensation when adjusted for cost of living among the 50 states, District of Columbia and U.S. island territories in 2023, according to a report published by the National Center for State Court.

District and superior court judges are paid $145,642. Supreme court associate justices are paid $155,397.

“There are many things that inform a person’s decision about whether to seek a judgeship — one of them is compensation. And the low compensation that has always been present in Maine, I don’t think there’s much question that it’s one factor that people think about,” said Saufley.

Being a judge can also be isolating, Saufley said.

The job comes with an inflexible schedule where arranging a haircut, dentist appointment or to attend a child’s school ceremony can be difficult if not impossible. Vacations are difficult to schedule and sick days are hard to take, she said.

On top of being on the bench, judges also need to research, read case files, review new laws and decisions — work that is often pushed off to weekends, Saufley said.

When there are more judges, then there are more colleagues to cover and assist each other, she said.

Instead the courts have seen the opposite occurring. There has been approximately a 40% turnover of judges in Maine since the pandemic began.

The courts operate best when there is a mix of new, energetic judges who challenge existing practices, and seasoned judges with skills and experience. A 40% turnover is not a good mix, Saufley said.

Study to shed light on judicial needs

The National Center for State Courts, an independent organization focused on court administration, did a weighted caseload study of Maine’s court system between October and November 2022. It didn’t specifically study how to reduce a backlog of open cases, though estimates have been shared publicly.

“A weighted caseload study provides a very good preliminary foundation for determining what it is the public needs from its system of justice,” said Saufley.

“For rural states, you may actually need more than just the data will tell you,” Saufley added. “Because you’ve got to cover regions where there may not be as many cases as one judge would handle, but you still need to have that judge in the region.”

The study isn’t expected to be published until April, though the state court administrator, Amy Quinlan, has cited the report’s preliminary findings in recent testimony to lawmakers in recent weeks as they work on the next budget.

Quinlan said projections of addressing the backlog by 2024 or 2028 aren’t “hard and fast” numbers, and several variables — including how many judges are added — could affect how soon the courts can begin to chip away at the backlog.

The study determined the court system needs 10 judicial officers and 54 clerks to keep up with court filings, Quinlan testified.

Maine’s courts didn’t close during the pandemic, but limits were placed on the number of people allowed in courtrooms to align with CDC recommendations. As a result, certain proceedings, including jury trials, were curtailed, creating what is referred to widely as the backlog.

The result was double- or triple-digit percent increases in pending cases statewide compared to 2019, according to reports released by the judicial branch.

New case filings were increasing in the decade prior to the pandemic, however.

Between 2010 and 2019, the amount of protective custody cases filed with the courts nearly doubled, increasing 93%. The length of time to close criminal cases also extended throughout the period, particularly with felony charges, a judicial branch’s review found, according to Quinlan’s testimony to legislators.

“The pandemic was the tipping point. It unmasked the reality that even before 2020, the courts and the judicial system were straining to keep up with the demand of cases,” Stanfill said during her speech.

Stanfill said last November that the state’s justice system was “failing,” and on Thursday she told The Maine Monitor that her perspective hasn’t changed.

“To be clear, it’s not the people in the judicial branch who are failing. We just don’t have the ability to serve the people of Maine the way they deserve. Things take too long. We can’t get to them no matter how hard we work,” Stanfill said.

Backlog remains a concern

The growth of the case backlog has slowed and decreased for some case types, Quinlan said.

“That backlog isn’t necessarily last in, first out or first in, first out. It is going to be determined by the priorities of the court or the ability of the court to put a particular type of docket together,” Saufley said.

Cases of violence or involving children are often prioritized by the courts, Saufley said. The Legislature also has a list of case types that it says the courts should prioritize.

Offering more settlement conferences where the parties of a case can reach a resolution without a trial is one way to address the backlog. Calling groups of cases to ensure defendants and prosecutors want to move to trial is another way, Saufley said.

The backlog has left many defendants and plaintiffs in limbo with their cases open longer than would be expected.

“The backlog has seriously affected the accused’s right to a speedy trial. For people who are incarcerated, this has resulted in languishing in jail for months — if not years — longer than before. Motions to dismiss for speedy trial violations, however, are not being granted,” said Nadeau, the defense lawyer.

She called on prosecutors to dismiss most misdemeanors and non-violent felonies, and for judges to dismiss with prejudice low-level cases to reduce the backlog.

“We can add judges, clerks, marshals, prosecutors and defense attorneys — but without mass dismissals the system will ultimately collapse,” Nadeau said.

Samantha Hogan reports on the criminal justice system for The Maine Monitor. Reach her with other story ideas by email: gro.r1753848854otino1753848854menia1753848854meht@1753848854ahtna1753848854mas1753848854.