The recession arrived not as a slow and predictable financial decline, but as a cliff.

Economists agree that Maine is experiencing an “unprecedented” economic downturn due to the coronavirus pandemic that has forced businesses to close and massive, rapid layoffs of employees. There is no past economic event that they can look to for guidance that matches the current decline in its scope or speed.

But with mixed messages from state and federal authorities on whether it is time to reopen businesses, the Maine Monitor spoke with four economists and one finance professor with intimate knowledge of Maine to understand where the state’s economy is headed and what past recessions may — or may not — tell us about how it will recover.

Interviewed individually, their responses revealed three common threads:

- A large, rapid downturn in Maine’s economy followed the arrival of a novel coronavirus that causes the respiratory illness COVID-19. While there is no single definition of “recession,” it is likely that Maine has already fallen into one.

- Unemployment is a wild card in this economic downturn. Unemployment typically lags behind a financial decline, but it is a leading indicator this time. Whether unemployment is temporary or permanent will play an important role in how long it takes Maine’s economy to rebound.

- Reopening will be dictated by consumer confidence in the state’s ability to control the spread of the virus through testing and contact tracing. Confidence may be restored slower for places such as restaurants or sports venues than large stores, where it is easier to be physically distant from others.

The current decline in Maine’s economy is first and foremost a public health crisis, said State Economist Amanda Rector.

“Until we manage to get the public health crisis under control we really don’t have a way to understand how deep the economic crisis will be or how to really bring the economy right back on board,” said Rector, who has been in her post since 2011.

The focus of the past several weeks has been on how to keep Maine residents and businesses afloat during the economic shutdown until the public health crisis was under control. With the number of active coronavirus cases still climbing but a surge of hospitalizations avoided at the moment, Rector and one additional analyst have begun piecing together a new picture of Maine’s economy.

To start: a bit of good news. The underlying conditions of Maine’s economy were in “reasonably good shape” in late 2019 and early 2020. Maine has money in the budget stabilization fund to get it through this fiscal year, which ends on June 30, Rector said.

There will be a hole in next fiscal year’s budget, but how large that will be is yet to be determined.

Maine received $1.25 billion in federal stimulus money from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act to help cover some of the costs of fighting the coronavirus. This does not include additional money that went to hospitals, universities and federally qualified health centers.

With Memorial Day weekend just a week away, now is when Maine would typically see its population swell to 2.5 to 3 million people as visitors flock to beaches, lobster shacks, campgrounds and Acadia National Park.

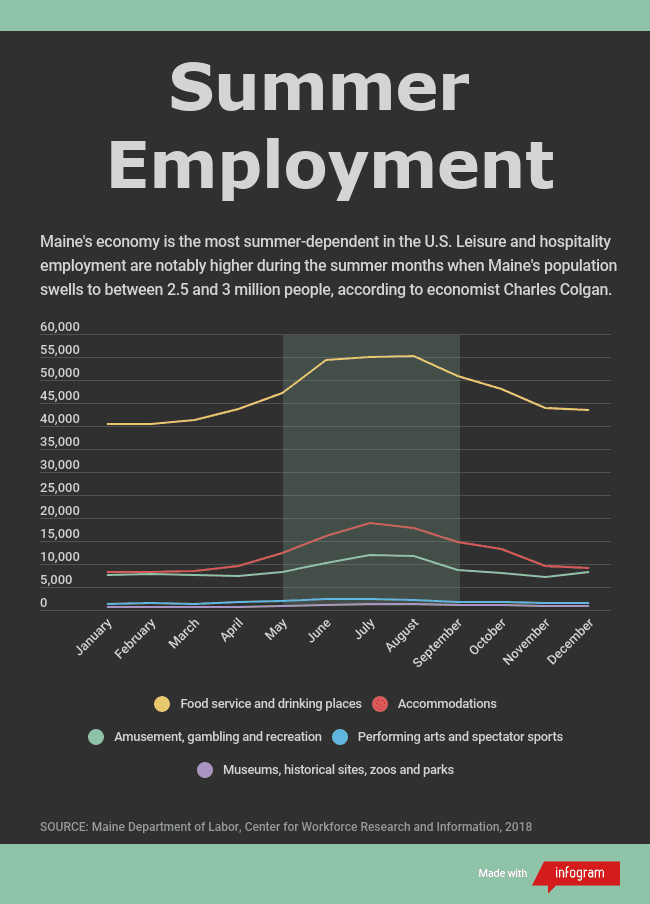

Maine has the most summer-dependent economy in the U.S., with leisure and hospitality employment notably higher in the summer, said Charles Colgan, professor emeritus at the University of Southern Maine and research director for Center for the Blue Economy.

While leisure and hospitality make up a significant portion of Maine’s employment — almost 11 percent, according to the latest Maine Economic Growth Council report — not all of Maine’s economy is dependent on tourism, said Steven Cunningham, professor of management and economics at Husson University. A year without summer tourism will have an effect, but it is not the only pillar holding up Maine’s economy.

Economists are staring down the barrel of two different nightmare scenarios, simultaneously. The first is a prolonged shutdown of the economy, in which businesses do not recover and unemployment becomes permanent. The other scenario has Maine businesses opening too quickly and a sudden resurgence of infections that require another shutdown.

Gov. Janet Mills convened an Economic Recovery Committee on May 6 to bridge the state’s reopening plan to its 10-year economic plan.

The recovery committee will focus on identifying barriers that could stand in the way of rapidly kickstarting economic growth and stimuluses that could aid it as the state economy restarts, said Laurie Lachance, president of Thomas College and a former state economist. She will co-chair the recovery committee with Tilson CEO Josh Broder.

Maine businesses will not be able to operate as they always have, and this needs to be a period of innovation, she said.

“Prosperity is not about your form of government, your economic underpinnings, your access to natural resources — it’s not about that. It’s about your people’s ability to innovate and draw on those things that are authentically yours,” Lachance said.

“The way we come out of it is taking that rich knowledge and body of experience and recreating the future by innovating it to the new products and services. That’s where we find our greatest success.”

Unemployed amid uncertainty

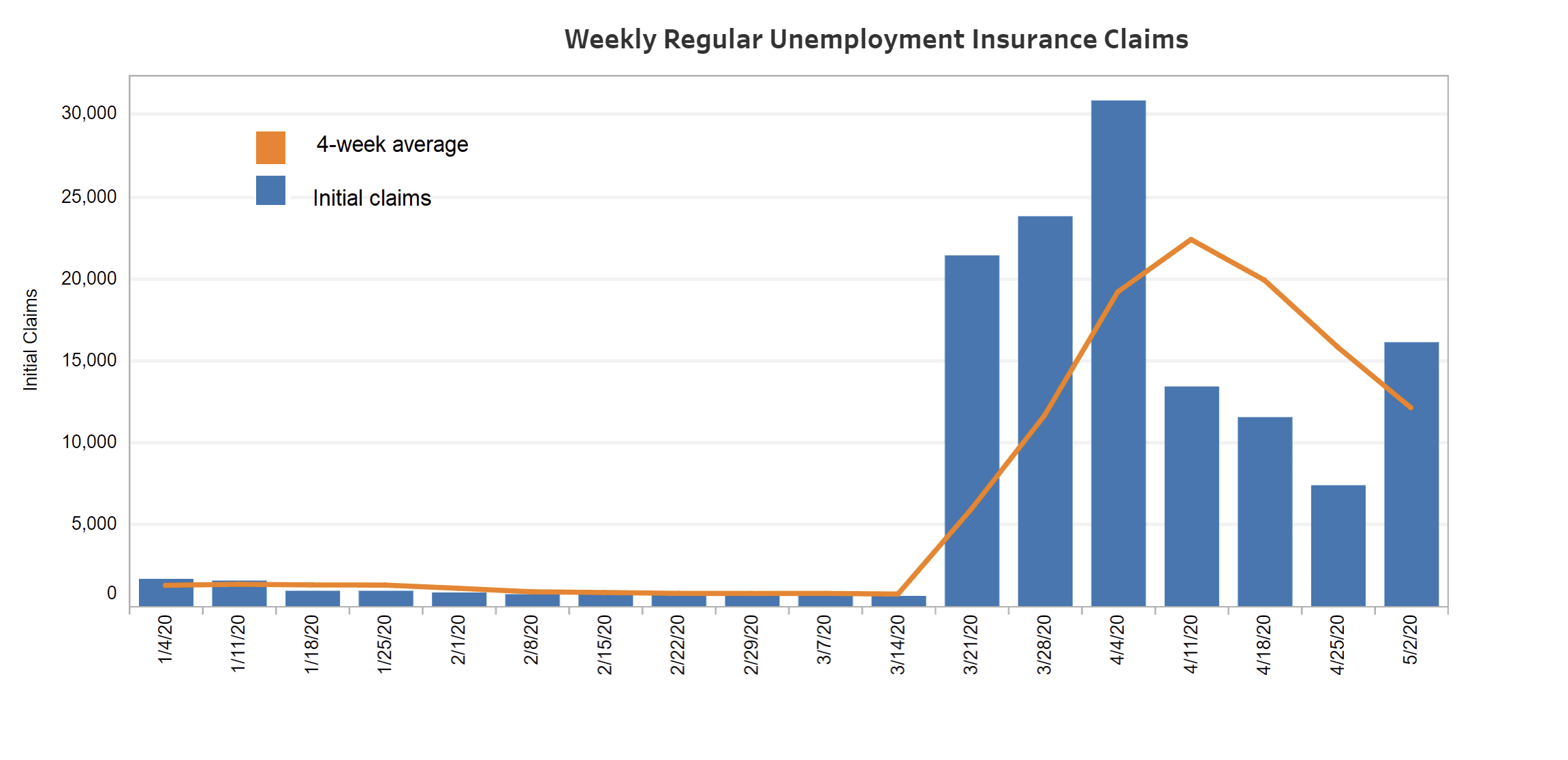

Between the discovery of the first case of COVID-19 on March 12 and the first death on March 27, employers shut their doors and laid off or furloughed tens of thousands of employees.

The resulting spike in unemployment broke economic forecasting models. The Maine Department of Labor reported a 3,285% increase in initial claims of unemployment between the week ending March 21 and the week before. The next six weeks continued to shatter records.

It doesn’t take bar charts and trend lines to see what the coronavirus has done to employment in Maine.

J. Douglas Wellington, a finance professor at Husson University in Bangor, hasn’t traveled far beyond his Castine home since Mills put the stay-at-home order in place. But a friend’s description of Ellsworth as a ghost town, with stores dark and parking lots empty, stuck with him.

“The number of new jobless claims — that’s very concerning,” Wellington said.

At Husson, Wellington created a stock index of 29 publicly traded companies that are headquartered in Maine or have a significant number of employees in Maine that he uses to analyze the state’s economic well-being. An Associated Press report on unemployment claims caught his attention last week. While the number of claims decreased in most states, they rose in six states including Maine, where the increase was 111.1 percent.

“We had the dubious distinction of having the largest increase in weekly jobless claims, when 44 states were already reporting decreases in jobless claims,” Wellington said. “I’d certainly like to see that number go down.

“As the jobless claims go down, as the unemployment rate goes down, obviously, that’s indicating we’re coming back,” he added.

Just as the downturn was visible in the empty streets of Ellsworth, evidence of recovery will be tangible in everyday life, too, Wellington said. His wife reported that stores and parking lots in Bangor were “as full as they could be with social distancing,” when she traveled there last week.

“Some of those not-really-economic indicators are also going to give a feel for whether or not we’re coming back,” Wellington said.

One of the biggest unknowns is when those who are unemployed will be able to return to their jobs. If furloughs are temporary and workers can return to their pre-pandemic jobs, then the economy can pick up quicker, Rector said. If unemployment is permanent, then the recovery will be delayed due to time lost to hiring and training new employees.

Multiple economists interviewed by the Maine Monitor shared a common concern about the future of small businesses in Maine. The small businesses that make New England towns “interesting” and “quaint” offer a lot of employment but they are also one of the largest vulnerabilities in the state’s economy, Cunningham said.

“The problem is that many of these businesses do not have large cash reserves, they are living on their cash flow,” Cunningham said. “When you have an interruption to the income stream, it’s devastating, which means that the longer that the shutdowns of the economy go on, the worse it’s going to be because they simply don’t have the reserves to make it for a long period of time.”

Either the stores will never reopen or a portion of their customer base will not return, he predicted.

Where unemployment hurts is in the home. Lachance describes her upbringing as one with “humble roots” with her first year at Bowdoin College costing as much as her parent’s house. In her nearly four decades as an economist, she has not seen worse unemployment.

Whether economists officially label the current downturn a recession or not, it’s going to hurt. People are going to feel like they’re in a recession, she said.

Frustration has already boiled over with approximately 100 people protesting outside the capitol demanding Maine reopen. Republican state lawmakers too have called for the legislature to reconvene to consider the removal of emergency powers from Mills.

Mills extended the civil state of emergency in Maine for an additional 30 days to June 11 on Wednesday.

The federal government is currently propping up the U.S. economy with zero percent interest rates and federal borrowing. How long Maine can afford to stay closed depends on what Congress decides to do next, Colgan said.

The Federal Reserve is “pouring money” into the economy at almost “unprecedented” levels, which has increased the U.S. money supply by slightly less than 20 percent in roughly the past month, Cunningham said. That’s equal to a year’s increase to the money supply.

Cunningham was on the Federal Reserve’s Board of Governors in the late 1980s, where he worked with price data to predict inflation rates and optimize monetary policy. USA Today broke down how money goes from newly created electronic dollars to securities to actual money in a bank on Tuesday.

Cunningham cautioned that it’s easy to cling to unemployment data as the key metric to gauge how the economy is doing because it comes out every week. But bigger-picture data, like the GDP, which is released quarterly, can be more insightful — it just takes longer to report.

Today’s unemployment conditions were caused by the government sending everyone home from work.

“We made this data happen. We said go home. Don’t go to work,” Cunningham said.

What frustrates Colgan, whose research centers on coastal economies and flooding, is that what is happening in Maine and the U.S. more broadly is exactly what economists predicted would happen during a pandemic.

“The whole thing was not only foreseeable, it was foreseen,” Colgan said. “We know that one of the major effects of climate change will be to radically alter disease vectors and make these kinds of events more common. This is a once-in-a-century event. This could easily become once in every 20 years.”

It was right to treat the virus as a hazard but not its consequences, he said. The economic fallout of a pandemic is all man made.

‘Everything’s open, olly olly oxen free’

The shutdown of Maine’s economy has caused unemployment, but it’s also slowed the spread of the virus.

“The whole strategy with COVID-19 is to keep people from moving around and transmitting it,” Colgan said.

According to Colgan, to get a robust economy running again will depend on Maine’s medical and public health systems and how quickly the state can begin testing and contact tracing, which are the “bread and butter of epidemic containment.”

Because if the state rushes to reopen at the expense of public health, and has to close again, that is going to be more detrimental to the economy, Rector said.

Mills announced a strategic partnership with Westbrook-based IDEXX Laboratories, Inc. on May 7 to increase Maine’s weekly testing capacity by approximately 5,000 tests a week. The following day she released a revised rural reopening plan to open businesses in counties where there was no evidence of community transmission of the virus.

Retail stores reopened on Monday to limited customers and with enhanced cleaning and touch-free transactions in all but Androscoggin, Cumberland, York and Penobscot counties. Restaurants are scheduled to open to dine-in services on May 18, as are campsites and certain outdoor recreation businesses to Maine residents or out-of-state visitors who have completed a 14-day quarantine.

More testing supplies is good, but still not enough.

“That will help. Now triple it and triple it again, and you might begin to make a dent in the effects on tourism,” Colgan said. “It’s numbers. It’s just sheer numbers. We really can’t pull over everybody as they come through the York tolls … and have them take a test. It might be a good idea, but we can’t do it.”

Even if Mills were to lift her executive order and reopen all Maine businesses next week, customers would still need to feel comfortable shopping or dining.

“Let’s say the state says, ‘Everything’s open, olly olly oxen free.’ Are you going to go sit in the restaurant? Ehh, I don’t know. At a minimum, there’s going to be fewer people going into the restaurants for a while,” Cunningham said.

It’s called consumer confidence, and it’s tricky because it hinges on whether people feel safe.

At Thomas College, the customers are 18-to-24-year-old students and their parents. Lachance made the difficult decision to move students online for the remainder of the spring semester after reading a “heartfelt, painful” email from one set of parents, who begged her to close the college and send their daughter home. It kept her up that night.

“Fear makes it hard. And when it’s your child, it becomes very personal very fast,” Lachance said.

Thomas College plans to reopen for the fall semester for in-person instruction, but with fewer students per classroom and extra dorms set aside to quarantine students who may be sick or exposed to the virus. There will also be additional cleaning and counseling staff added to protect student health.

One of the longest-running surveys of registered voters in Maine showed that more than one-third (38 percent) believed the country was “striking the right balance” between minimizing the health impact of the coronavirus and the need for a healthy economy in March. Another third said the country was “too worried about the economy.”

The survey also found that 9 of 10 Mainers had avoided public places as a result of the coronavirus, such as restaurants.

“You see substantial evidence from the survey research that people don’t care what’s open, they’re not going anywhere. That may be actually the biggest hurdle to all of this coming back together again. It’s not what the rules are, but what people feel is safe,” Colgan said.

During a normal recession, not a pandemic, economists could model and say, “Where this line crosses, we’ve got to be open,” Lachance said. But in the case of a pandemic, the ability of any business in any sector to operate depends on the health of employees and customers, she said.

How well social distancing can be implemented at stores, restaurants or sports venues will be crucial to building confidence; as will keeping the spread of the virus under control.

Businesses cannot open and be the purveyor of disease, because that will kill a business too, Lachance said.

“We can’t afford to stay closed long, but we can’t afford not to stay closed long enough to make the situation as safe as we can,” Lachance said. “There will be parts of this that we cannot prevent and we understand that. But to the extent that we can prevent the rapid transmission, we have to stay closed long enough to do that or we’ll do it at our own peril.”