The Maine Climate Council has just finished updating the state’s climate action plan, as required by law, and a key strategy in the draft plan is to put 150,000 electric vehicles on Maine roads by 2030. Despite good intentions, this seems doomed to fail.

I’m making that assessment as a journalist who has covered Maine energy issues for many years, and as someone whose extended family has three hybrid vehicles, one plug-in hybrid and one all-electric SUV.

My dive into the latest statistics and the shifting electric vehicle markets suggests to me that state climate planners once again put aspirations ahead of reality.

The plan was drafted just before the election, which means it also failed to account for a looming political reality: The incoming Trump administration will embrace energy policies that favor fossil fuels. That portends an uncertain future for the federal rebates that have lowered purchase prices up to $7,500 for many electric vehicle buyers.

Having said that, new battery and electric vehicle factories are popping up in red states, and Tesla CEO Elon Musk is bound to get something for his $100 million-plus donation to Trump’s reelection.

Maine’s climate law mandates a 45% reduction in 1990-level greenhouse gas emissions by 2030. Because transportation accounts for nearly half of Maine’s total carbon emissions, targeting cars and trucks makes sense.

But a closer look at how the market has reacted since 2020, when Maine first issued its climate action plan, indicates that the latest targets are not only unrealistic, but might not have their intended climate impact.

First, let’s look at where we are.

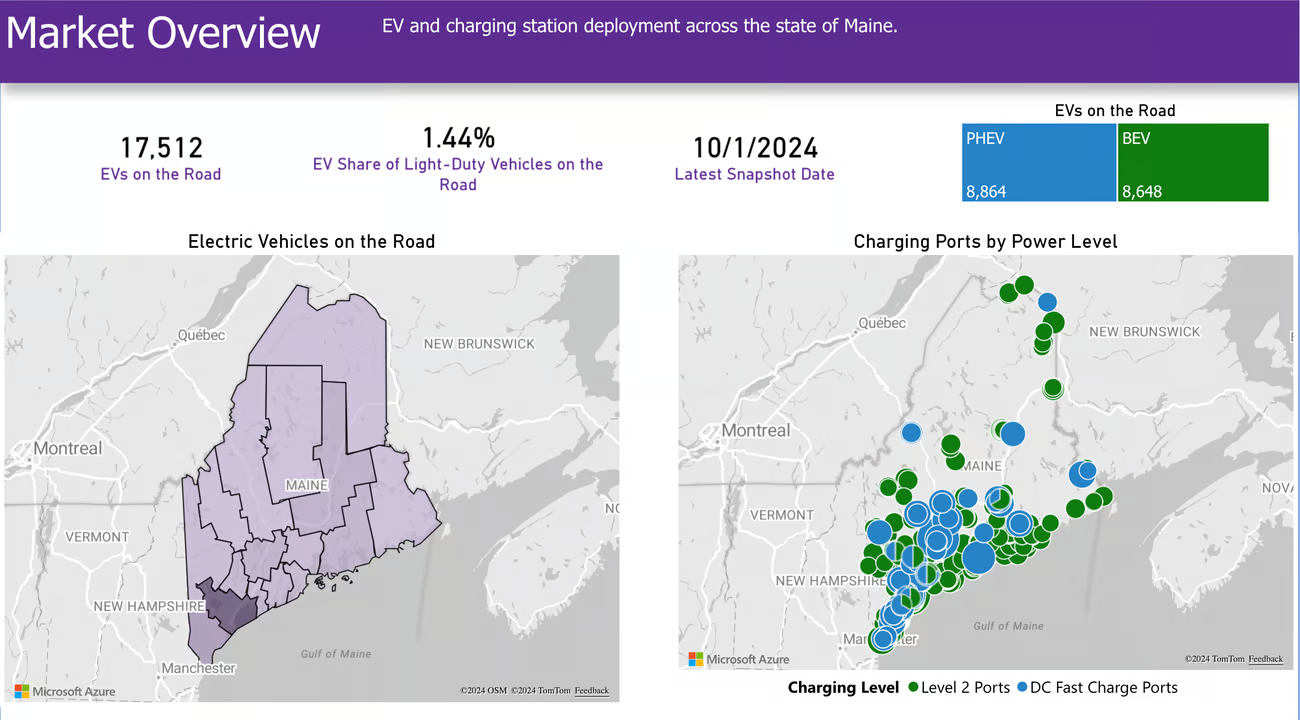

The latest data shows Maine has more than 17,500 registered electric vehicles, more than double what the state had four years ago. Early this month, Efficiency Maine reported it was suspending its state rebate program because a jump in qualified purchases — 190 in October — had exhausted the $3.5 million allocated by the Legislature in 2022, according to Maine Public.

Taken together, this seems like progress. But it only looks impressive because we started from next to nothing. Meanwhile, there are still more than 1 million gasoline-only vehicles registered in Maine.

Keep in mind, Maine’s 2020 plan set a goal of 219,000 electric vehicles by 2030. This fall, in a belated acknowledgment that this was impossible, a consultant scaled back the target to 150,000 “light duty battery electric and plug-in hybrid vehicles.”

Let’s unpack those terms. Light duty battery electric vehicles are fully electric, operating only on battery power. Plug-in hybrids have smaller batteries that are backed up by conventional gasoline engines, which take over when the batteries run out of charge (within 30 or so miles on average).

Remember those 17,500 electric vehicles registered in Maine? The latest figures from Recharge Maine show that only about half of them are fully electric. The largest share is made by Tesla, notably the best-selling Model Y. The other half are plug-in hybrids, often versions of Toyota’s popular Prius and RAV4.

That means half of the registered electric vehicles in Maine also have gasoline engines. This is an important distinction.

Researchers are finding that many people who own plug-in hybrids don’t always bother to plug them in, leading to gasoline consumption 42 to 67% higher than expected.

Last year, 83% of plug-in hybrid sales were sports utility vehicles, according to Green Car Reports. SUVs typically are heavier and less efficient than cars, so the carbon reductions are smaller.

Adding to the confusion, automakers have been ramping up production of plug-in hybrids to entice buyers who are hesitant to go fully electric. But these vehicles accounted for fewer than 2% of new car sales in the United States during the first half of 2024, according to a survey cited by Green Car Reports. Fully electric vehicles reached above 9% and straight hybrids (which recharge their smaller batteries using their gas engines) accounted for nearly 11%.

Electric vehicle advocates don’t like straight hybrids. But Toyota, which sells more vehicles worldwide than anyone, is leaning into these models. Next year’s best-selling Camry is only available as a hybrid. The company has argued that the cost of critical battery-making materials such as lithium, the still-insufficient number of public charging stations and the high average prices for electric vehicles make straight hybrids a more effective way to cut overall carbon emissions in the short term. It’s a controversial calculation that’s rejected by those who envision an energy economy powered solely by electricity.

Maine’s new climate plan doesn’t even mention straight hybrids as part of the solution. It’s a stance I questioned last year in a column about Maine’s all-electric priorities, in which I detailed Toyota’s strategy and claims. Recharge Maine doesn’t tally straight hybrids, but there were more than 33,000 registered here as of last year, according to the federal government’s Alternative Fuels Data Center. So even without rebates, straight hybrids are by far the top choice in Maine for people looking to drive cleaner vehicles.

This is a complicated time in the electric vehicle transition. The average battery electric vehicle price is above $50,000 and loan rates remain high. Automakers keep adjusting their prices and output in an effort to sell the vehicles that Americans want and can afford. Ford, for instance, is pausing production on its F-150 Lightning pickup to shore up losses on a truck that costs between $57,000 to $95,000.

Smaller electric vehicles are more affordable. And in public comments on the latest climate plan, leading environmental groups pushed for higher financial incentives to get low- and moderate-income drivers behind the wheel. That’s fine policy from an equity standpoint, but will it move the needle on climate?

Here’s a personal example: Last summer I purchased a Kia Niro plug-in hybrid, a compact hatchback that starts at roughly $35,000. I was happy to take Efficiency Maine’s $1,000 rebate, but would have bought the car without it. And in the first 2,000 miles of driving, I used only 10 gallons of gasoline.

But in truth, my climate impact is of little consequence. I don’t commute to work anymore. I rarely take the car farther than 40 miles round trip, which is why I can do 90% of my driving on the battery.

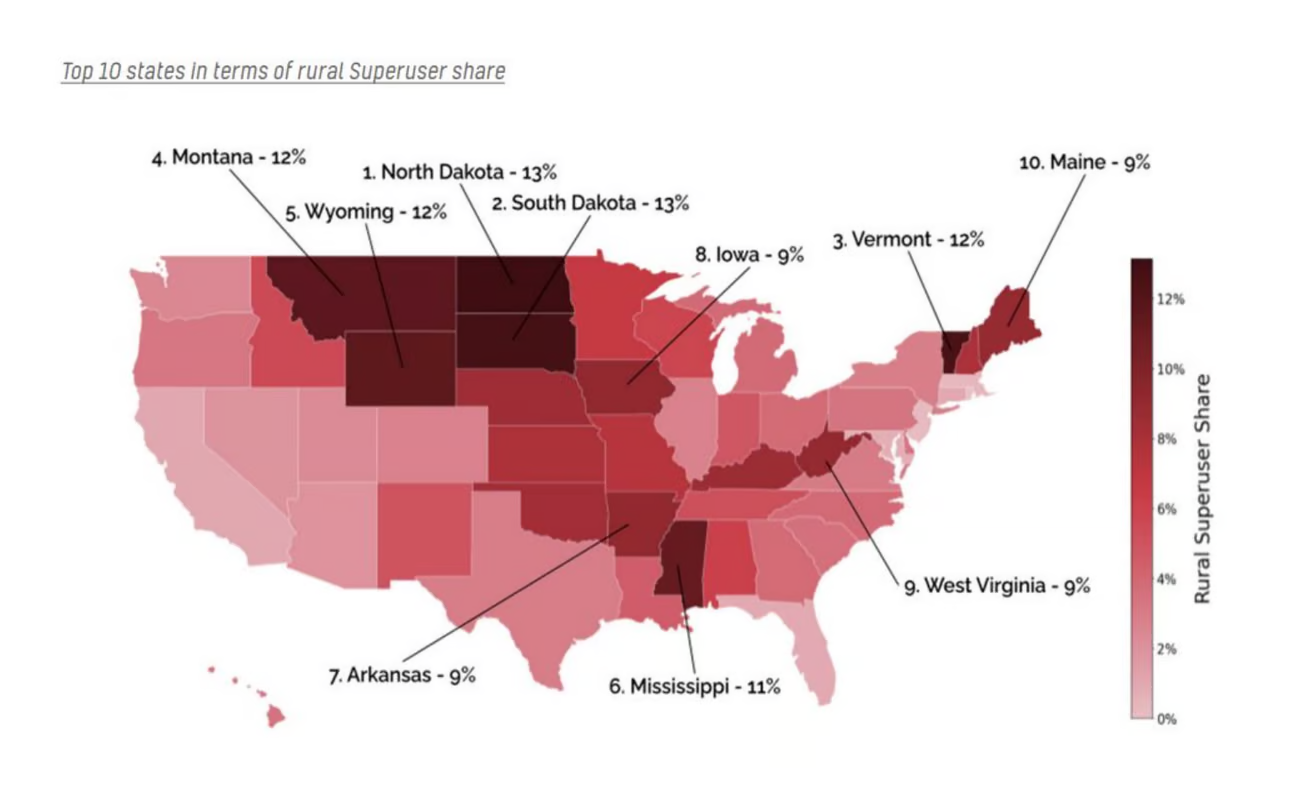

If Maine wants to have the greatest impact, it should stop just counting the sheer number of electric vehicles and focus incentives on the subset of drivers known as gasoline superusers.

That’s the view of Coltura, a Seattle-based non-profit that uses data to promote gasoline-free transportation. It submitted public comments to the Maine Climate Council.

The group defines superusers as the top 10% of drivers in the U.S. in terms of gasoline consumption. In Maine, Coltura identified 118,000 superusers. They make up 14.5% of total drivers but use 41% of the gasoline, or 223 million gallons per year.

Getting these drivers into electric vehicles, the group calculated, would cut Maine’s transportation emissions by nearly 19%. Even when accounting for electricity costs, the switch would save superuser families, on average, $255 a month on fuel.

Coltura had two key policy suggestions: Target electric vehicle education and outreach to superusers, promoting the financial savings. Modify Maine’s rebate program to prioritize low- and moderate-income drivers who are also superusers.

To be fair, the climate council faced a tough task in trying to figure out how to reduce transportation emissions. Mass transit can only help around the edges in a largely rural state, where people drive longer distances and are more likely to drive used cars.

With Americans now holding on to their vehicles for a record average of 12 years, it’s hard to imagine what level of financial incentives would be needed to get 150,000 electric vehicles on the road by 2030.

Correction: This article has been updated to clarify Elon Musk’s connection to Tesla. He is the CEO, not the sole founder.