Editor’s Note: The following story first appeared in The Maine Monitor’s free environmental newsletter, Climate Monitor, that is delivered to inboxes for free every Friday morning. Sign up for the free newsletter to get more important environmental news from reporter Kate Cough by registering here.

Earlier this week, as I was mulling over what to write about for this newsletter, a friend texted a picture of her afternoon snack: oysters, fresh from the nearby wharf, artfully displayed on a striped cotton napkin, the tapered end of a shucking knife visible in the corner of the frame. A casual Wednesday evening, complete with mollusks.

Oysters have become an increasing presence in my life over the past few years. Beach bonfires, once the firmly-held territory of hot dogs and mussels, have ceded ground to Crassostrea virginica, smoked in a cast iron skillet. They’re popping up at lobster bakes and birthday parties, nestled beside ice buckets full of IPAs and rosé. My husband and I recently sold our ancient Frigidaire to someone who said he was going to use it exclusively for oysters, which he planned to sell in his shop alongside ice cream and bicycle rentals. Friends have developed oyster preferences (Bagaduce or Long Cove? Mere Point or Burnt Coat?). I’ve even had oysters served to me for breakfast, beside a heaping plate of scrambled eggs. The knobby, salty bivalves seem to be everywhere, in a way that they never were when I was growing up on the coast in the 1990s.

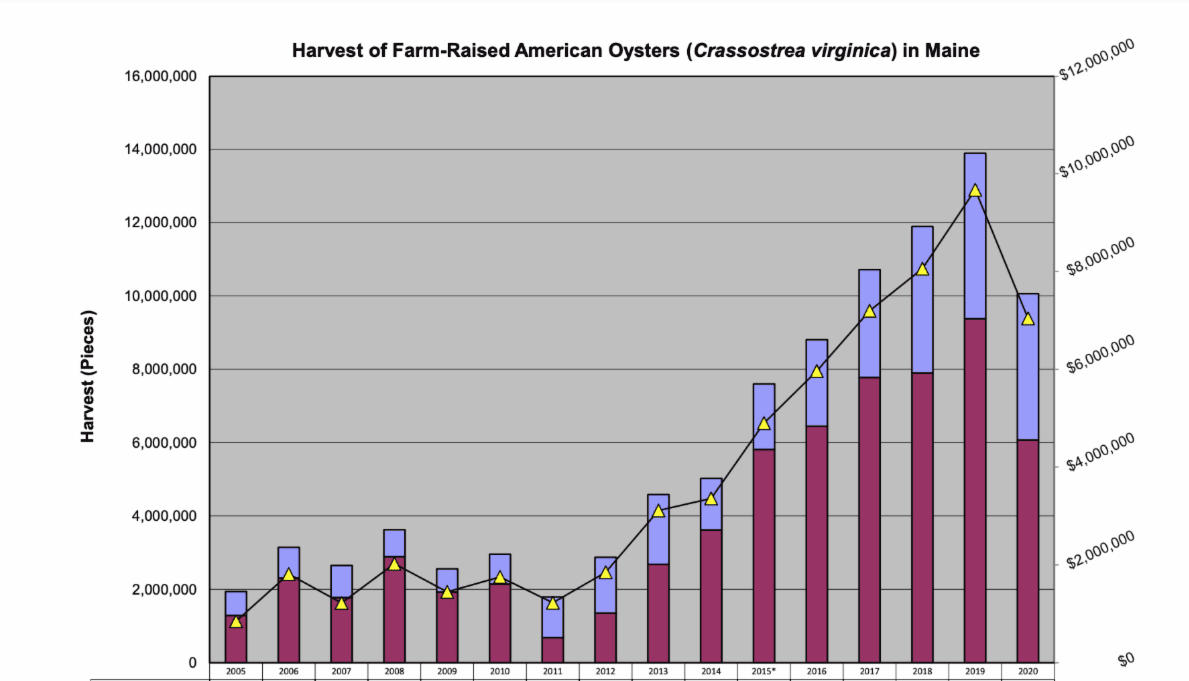

Perhaps that’s because they are. Maine’s 2021 oyster harvest was the largest and most valuable in its history, with harvesters hauling in more than 6 million pounds in 2021. That’s an increase of 55% over 2020, and more than twice what it was just five years ago.

Oysters have been growing in Maine’s brackish waters and tidal estuaries for thousands of years. They were harvested by the native Wabanki (one can still stumble upon ancient middens, or shell heaps, along coastal riverbanks) and were still abundant upon the arrival of European settlers in the 1600s.

But predators (both human and otherwise) and colder temperatures (oysters cannot spawn if the water is too cold) eventually decimated the native population. Pollution from the shipbuilding and other coastal industries killed off what pockets of wild oysters remained.

It wasn’t until the 1970s, when University of Maine researcher Herb Hindu established a program and hatchery, that oyster farming began a slow return to the Maine coast. In the intervening decades, faculty and students experimented with ways to breed oysters better adapted to the state’s cold waters, and in the 1990s, researchers introduced seed oysters (also known as “spats”) into a few sheltered inlets.

It’s been a slow climb back, but the past few years indicate their push to return the mollusks to state waters is working. Of the 698 active limited purpose aquaculture licenses listed by Department of Marine Resources, an astonishing 77% include oysters, primarily the American or eastern oyster, Crassostrea virginica, native to the east coast from the Gulf of Maine to the Gulf Mexico. (A single operator can hold multiple licenses, and some grow multiple species, such as sugar kelp, scallops or quahogs.) Oysters were the fourth most valuable marine resource in the state in 2021 (although they still accounted for just 3% of landings by weight, far behind that titan of Maine seafood, the lobster, at 52%).

The vast majority of oysters grown in Maine are farmed, a process that differs depending on the operation. They can be grown in cages or bags, floated or suspended below the surface. Some are even free-planted on the ocean floor before harvesting. Raising oysters to market size takes about three years, and although it can be done year-round, they’re most plentiful from spring through fall. Since they don’t naturally spawn in Maine’s cold waters, growers must buy baby oysters from hatcheries, of which Maine has several.

But there is also recent evidence of “wild” oysters surviving outside of cultivation sites, a phenomenon that may be due in part to warming waters linked to climate change, as Dana Morse, who works for Maine Sea Grant in South Bristol at UMaine’s Darling Marine Center, told the Bangor Daily News last year.

Decades ago, said Morse, it was rare to see an oyster survive outside a cultivation site.

“It would happen every once in a while, but generally it didn’t happen.” Now it’s an annual occurrence. Their habitat has also shifted east in the past few decades, and commercial harvesters are trying their hand at farming oysters as far east as Deep Cove, off Beals Island in Washington County.

But the oyster boom is not without its critics. Longtime fishermen fear losing productive grounds to farmers, Crystal Canney, executive director of Protect Maine’s Fishing Heritage Foundation, told the Associated Press earlier this week. The group would like to see a comprehensive plan for shellfish to help manage the increase in leases.

Although industrial-scale aquaculture has gotten a lot of attention in recent years, the Department of Marine Resources has not made moves to restrict limited purpose aquaculture, which accounts for almost all of Maine’s oyster harvest. Under those rules, licensees are allowed up to 400 square feet of area for one calendar year to grow certain shellfish species and marine algae. Only certain kinds of gear are allowed.

“We are seeing people treating this like a Wild West gold rush,” said Canney, of the explosion in growers looking for ocean acreage. “And it’s irresponsible.”

To read the full edition of this newsletter, see Climate Monitor: oysters, oysters everywhere.

Kate Cough covers climate change and the environment for The Maine Monitor. Reach her by email with ideas for other stories at gro.r1757729709otino1757729709menia1757729709meht@1757729709etak1757729709.