State lawmakers are considering nearly a dozen pieces of legislation to better regulate PFAS, a group of “forever chemicals” associated with various health risks, and widely used in industrial processes and household products.

The bills will pass through the Legislature just weeks after a Fairfield resident filed a class action lawsuit against Sappi North America, claiming that PFAS found in Somerset County water sources originated from the paper mill company’s wastewater treatment plant in Skowhegan. The lawsuit is open to county residents who were affected.

The long-term harm these chemicals pose to public and environmental health is well-documented as they don’t break down through biological processes. These endocrine-disrupting chemicals have been linked to various types of cancer, reproductive harm and thyroid issues.

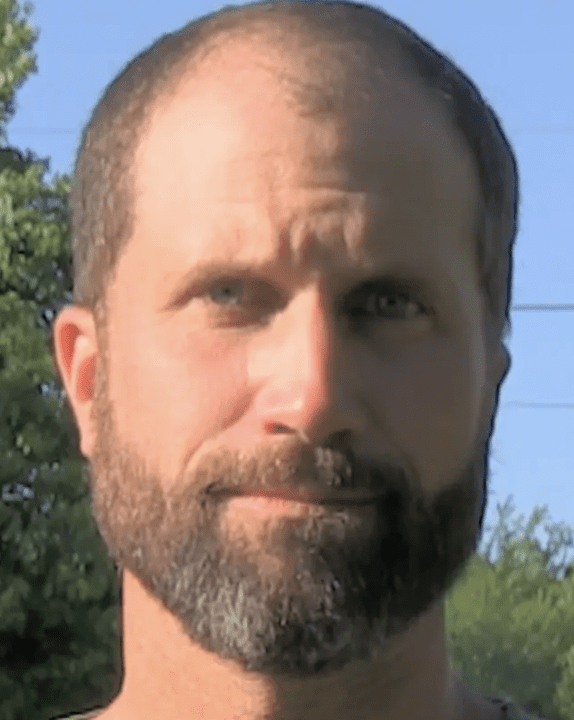

“We all have PFAS in our bodies that (are) going to be there, more likely, until the day we die,” said Rep. Bill Pluecker (I-Warren) who is sponsoring five pieces of legislation related to PFAS. “We need to protect our kids, and our families and our businesses.”

Two of Pluecker’s bills would set maximum statewide contaminant levels and require public testing of drinking water supplies.

The legislation would decrease PFAS maximum contaminant levels to 20 parts per trillion, much lower than the EPA’s 70-parts-per-trillion health advisory levels, but would put Maine on track to match state-mandated PFAS levels in New Hampshire, Vermont and Massachusetts.

“We’re behind in terms of the contamination levels with our New England neighbors,” said Sarah Woodbury, director of advocacy at Defend Our Health, a Portland-based nonprofit. “Twenty parts per trillion is really important to start going in the right direction of setting a health protective standard for PFAS in drinking water.”

Defend Our Health played an active role in introducing PFAS legislation and its executive director served on Gov. Janet Mills’ PFAS task force, which was established in March 2019. The task force studied the extent of PFAS contamination in Maine and published recommendations for how to best protect Mainers in a January 2020 report.

Mills has since established a fund to address PFAS contamination and has urged the federal government to provide financial assistance.

“PFAS contamination is not a Maine problem; it is a national problem that ultimately requires a federal response,” Mills wrote in a March 31 press release.

PFAS were first identified in Maine goundwater in 2016 near historic military sites, but their danger was fully realized when wells near Kennebunkport and Wells became contaminated. This led to the discovery of alarming PFAS levels — up to 1,420 parts per trillion — at a nearby dairy farm in Arundel.

The discovery at the farm unearthed the pervasive nature of PFAS contamination on Maine farms where PFAS-contaminated biosolid sludge had been applied. In the 1980s and 1990s, the state Department of Environmental Protection approved the spreading of contaminated sludge on 500 sites.

“Those (500) sites — because of the nature of PFAS — may still be contaminated,” said Pluecker, who is an organic farmer. “We need to have a way of helping those farmers out so they’re not going out of business.”

Several bills would lend financial support and bolster legal options for citizens living or working on PFAS-contaminated sites. Last week the Judiciary Committee unanimously supported a bill that would extend the amount of time Mainers are able to seek civil recourse for damage caused by PFAS contamination.

Currently, people impacted by PFAS contamination can seek recourse six years from the date of initial contamination, but the new bill would extend the time frame to six years after the contamination was discovered.

RELATED: Sea Change: Ending the ‘Silent Spring’ on commercial forest lands

Of the five PFAS bills referred to the Environment and Natural Resources (ENR) Committee, two are being presented by Rep. Jess Fay (D-Raymond) on behalf of the DEP.

One would define PFAS and other toxic chemicals as hazardous substances so the DEP can tap into state funds to clean up contaminated sites. The other would require companies knowingly manufacturing or discharging PFAS products to report their actions to the Maine DEP.

Of the three other bills being considered in ENR, one would require the DEP to test PFAS-contaminated sites, and create a fund to pay for testing costs and disposal fees. The other two bills deal with the prevention and phase-out of PFAS in products ranging from residential carpeting and rugs to firefighting foam.

“Moving away from the use of these toxic chemicals can overall help both the health and environment of all Mainers,” said Woodbury. “Stopping (PFAS) at its source is the end game here so that we don’t have to continue to deal with the impacts.”

Woodbury said requiring the phase-out of PFAS in avoidable products by 2030 puts Maine at the forefront nationally.

“No other state has kind of taken this up,” she said. “We’re actually leading on this particular issue.”

The Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry Committee is also considering two pieces of legislation — a bill that would cease aerial spraying of PFAS-laden pesticides in Maine and resolve to investigate the most cost-effective way of remediating cropping systems on PFAS-contaminated farms.

“We’re definitely being proactive in how we’re addressing (PFAS), partly because we’re such a mix of rural spaces and urban spaces,” said Pluecker. “Maine’s ahead of the curve.”

Sustainable seafood leaders see ‘Seaspiracy’ as oversimplification

The Maine Coast Fishermen’s Association hosted a virtual panel discussion this month with experts across the seafood industry to unpack concerns with “Seaspiracy,” a new Netflix documentary about the impacts of commercial fishing.

Film participants along with scientists and conservationists voiced concern over misinformation presented in what panelist Jessica Hathaway, editor-in-chief of National Fisherman magazine, considers a “docudrama” and “fake news.”

“One of the problems with this film is that it takes worst-case scenarios and then extrapolates them to be bigger than they are,” said Hathaway at the April 9 event.

The film cites a 2006 statistic claiming the oceans will have no fish by 2048, which has since been debunked and called into question by one of the lead scientists who authored the 2006 study, Dr. Boris Worm of Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Worm told the BBC, “Since (2006) we have seen increasing efforts in many regions to rebuild depleted fish populations.”

Ben Martens, executive director of the Maine Coast Fishermen’s Association, also noted during the panel discussion the success of rebounding fish populations in the United States and parts of Europe.

“We’ve seen some fantastic results from our science-based management when it comes to rebuilding our fish stocks,” he said.

Fish stocks in the United States are managed by the federal government through annual catch limits. Catch limits are based on assessments that estimate the maximum amount of fish that can be harvested each year to ensure the health of future fish populations. If a species is overfished, the federal government will prohibit fishing a certain species to give it time to rebound.

Panelists acknowledged the 90-minute film brought up important issues related to overfishing in places with less stringent rules than the United States. The conversation touched on a multitude of topics impacting global fisheries — from underreported catches caused by illegal fishing to human rights abuses, and stressors like ocean acidification and nutrient pollution, which are worsened by climate change.

“It’s really important for people to wrestle with some of these big issues. What (the film) didn’t do well was help give people some solutions,” said Linda Behnken, a commercial fisherman and executive director of Alaska Longline Fishermen’s Association.

While solutions were scarce, questions were abundant. “Seaspiracy” questioned the integrity of sustainable seafood labels from nonprofits like the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC), which declined interviews for the film but responded with this statement.

While the labeling system has been questioned before, it’s a benchmark aimed at informing seafood consumers their fish was caught in the wild without depleting fish stocks or harming other wildlife. MSC’s sustainable seafood labeling system relies on independent third parties verifying the sustainability of the 400-some MSC-certified fisheries worldwide, according to panelist Michael Conathan, an ocean policy advisor at the Aspen Institute.

“If you don’t tell the whole story, you’re leaving people with a false impression of what’s actually taking place,” said Conathan.

The film ended with a warning that the bioaccumulation of plastic and contaminants in fish are toxic to consumers, and advocated for people to go vegan to take pressure off fish stocks, and avoid toxins. The seafood boycott has come under scrutiny as a privileged, saviorist solution. Many communities depend on fish as their sole source of protein and lack the resources to switch to a plant-based diet.

“Blanket statements that scare people away from a dissection of what is a much larger and much more complicated truth … get to be actually damaging to public health,” said panelist Barton Seaver, a Maine-based chef and author focused on sustainable seafood education.

Seaver pointed out that while environmental toxicity can be damaging to vulnerable human populations, species whose toxicity outweighs the nutritional benefit of omega-3 fatty acids — shark, king mackerel, and marlins — are not widely served.

“What we really need to question is where those (toxins) are coming from and what we can do to stop those toxins from washing into the ocean,” added Behnken, a commercial fisherman in Alaska. “If you stop eating seafood it does nothing about the poison that’s coming into the ocean. It does nothing to protect the fish.”

Back to the drawing board for Kennebec River Management Plan

The Maine Department of Marine Resources will take a new approach to its Kennebec River Management Plan after fielding over 1,100 public comments on a hotly contested proposal that would improve fish passage by removing up to four dams.

The amendment was scrapped after a U.S. subsidiary of a Canadian energy company that owns the dams sued the state in March.

The company — Brookfield Renewable Partners — claims the proposal is “invalid under state law” and the department “overstepped its authority” by not consulting with other state agencies before calling for significant changes to the management plan, reported Caitlin Andrews of the Bangor Daily News.

The killed proposal recommended removing two dams owned by Brookfield between Waterville and Skowhegan, and studying whether two others should be eliminated. The removals would support five species of struggling fish, including the endangered Atlantic salmon. Those in support of removing the dams are concerned with fish passages while a handful of Maine towns along the Kennebec River oppose it, citing the potential for increased property taxes.

The pulled amendment and pending lawsuit come as the Shawmut Project, a dam in Fairfield, is up for relicensing with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. The agency will decide whether to renew the operation for 30 to 50 years, taking into account state regulatory recommendations.

The Mills administration announced intent to include more stakeholders in its revised plan before federal regulators make a decision.

Atmospheric carbon concentrations peak

On April 3, researchers at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography logged record-breaking concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere — levels that are twice as high as those observed before the Industrial Revolution. The institution maintains the longest-running daily tally — called the Keeling Curve — of atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations.

Matthew Cappucci and Jason Samenow of The Washington Post reported on the issue.

“CO2 (carbon dioxide) accumulates in the atmosphere,” Zeke Hausfather, a climate scientist at California’s Breakthrough Institute, wrote to Cappucci and Samenow. “The amount of warming that the world is experiencing is a result of all our emissions since the industrial revolution — not just our emissions in the last year.”

The milestone comes as emissions are down due to the pandemic. But because of the long lifespan of potent gases like carbon dioxide, emissions reductions don’t provide immediate atmospheric results. The all-time high serves as a reminder that sustained emissions reductions will not slow climate change, but can help the impacts from worsening in the long run.