When Lynne and Abby Hasson faced off on Feb. 17, 2021, they made Maine high school basketball history. With Lynne as the varsity girls’ coach at South Portland and Abby leading Portland, they became the state’s first mother-daughter coaches to oppose each other.

It was also noteworthy because of how few women across Maine lead girls’ varsity basketball programs, and girls’ teams in general.

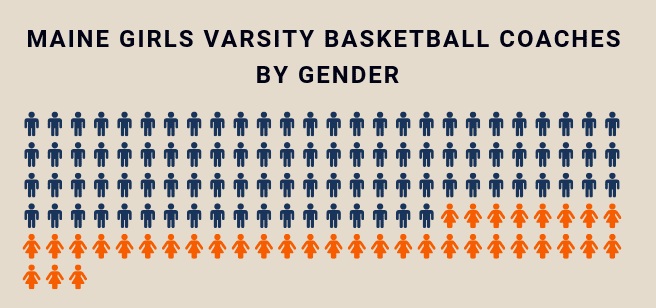

Overall, only 28 percent of varsity girls’ basketball teams across the state were coached by women this season.

That number is up from 21 percent in the 2019-20 season, which ended days before the first COVID-19 case in Maine, but down dramatically from the 51 percent in 1975, the first year girls’ basketball tournaments were sanctioned by the Maine Principals’ Association, the state’s governing body of high school athletics.

The dearth of women leading female athletic programs is an issue across Maine and the nation at both the high school and collegiate levels.

Coaching is centered around mentoring young athletes and instilling a love of the game. Coaching is about molding an athlete’s life during their most developmental years, and guiding them through life lessons.

“I think (having more female coaches) is so important … for the young female athletes that we coach,” said Lynne Hasson.

Other popular sports such as soccer and softball have somewhat better percentages but remain underrepresented: 39 percent of Maine girls’ varsity soccer teams and 39 percent of softball teams were led by women in the 2019-20 season.

Tennis recorded 42 percent and hockey, with fewer girls’ teams, was at 14 percent. Field hockey, sanctioned only for females, registered 99 percent, lacrosse was at 69 and volleyball at 63.

For boys’ and girls’ sports generally coached by the same person, swimming had women coaching 41 percent of the teams, followed by cross country (34), outdoor track (23) and indoor track (22.5). Golf achieved a measly 4 percent.

On the collegiate level in Maine, the numbers at times are significantly better.

The highest percentage again was field hockey, with 90 percent during the same 2019-20 period. Lacrosse (70 percent) had the second-highest percentage, followed by softball (61.5), volleyball (61.5), basketball (56), soccer (47), hockey (40), track (25), cross country (19) and swimming (12.5). There were no women collegiate golf or tennis head coaches that season.

Slightly more than 40 percent of women’s athletic teams in the NCAA were led by women in 2016, down from 55 percent in 1981 and more than 90 percent in 1972.

‘Imminently qualified’

Muffet McGraw, who spent 38 years as a college basketball head coach and won two NCAA national championships with Notre Dame, said there are two main reasons for the lack of women head coaches: People hire people who look like them, and since most athletic directors are white men, they are prone to hire white men. And the skills needed to be a head coach aren’t the same as those used to get the job.

“Women are imminently qualified to be head coaches, but when men interview they portray more confidence and bravado using the word ‘I’ quite a bit in talking about their resume,” McGraw said. “Women are taught to be humble and team players, and would never brag about their accomplishments – deferring to the word ‘we’ most of the time. In other words, men win the interview because they appear to be more confident in getting the job done.”

Others concur.

“Many of the female coaches in our Women’s Basketball Coaches in Maine group agree that women are not as confident about their abilities as our male counterparts,” said Husson women’s basketball head coach Kissy Walker, who is in her 31st year.

McGraw hired exclusively female coaching staffs during her final eight years at Notre Dame and said males coaching women’s teams should do the same.

“I’m disappointed that more (athletic directors) don’t strongly encourage a male head coach to have female assistants,” said McGraw. “These young girls that they are coaching need women on the staff so they can relate to someone about issues on and off the court.”

Next woman up: Preparing future coaches

Many say efforts to boost the number of women in coaching are hampered because women cannot see themselves in coaching positions through other women. Susan Robbins, the Gray-New Gloucester High athletic director who has over two decades of experience, agrees.

“I believe women need opportunities. They have to see it in order to be it,” she said.

Chelsea Crockett, 21, just finished her first season leading the Nokomis High varsity girls’ basketball team in Newport. It was only four years ago that she was playing for the team.

Crockett was fortunate to be exposed to all-women coaching staffs, who showed there were opportunities for her to continue in the sport.

“When you don’t see someone who looks like you in that role, it’s hard to feel confident in your abilities to fulfill the position,” Crockett said.

McGraw summed it up bluntly: “How will we ever get more female coaches if girls who play the sports look up and only see men coaching them?”

“Sports teaches us great life lessons, and building confidence and empowering women to believe in themselves is a big part of the job,” McGraw said. “Most men don’t deal with any of those important things and tend to just talk about the game, when every successful coach knows that team chemistry, trust and believing in people, especially after they fail, is what really matters. Yes, winning is important, but it isn’t the only thing we are hired to do.”

Krysta Porter is only 23 but living her dream as the athletic director at Mount View High in Thorndike, her alma mater. She is the state’s youngest athletic director. The lack of women coaching is discouraging and a result, she believes, of general stigmas placed on women about a perceived lack of sports knowledge.

“Honestly, I think there is still a huge stigma in athletics all over the country that females don’t know as much about sports as males do,” said Porter, who also served as the Mustangs’ junior varsity softball coach. “Females are continually questioned about their knowledge of the sport they are coaching, and that can be extremely frustrating, and discouraging to young females that want to get into coaching. They feel as though they have to prove their knowledge and coaching skills more than their male counterparts.”

Administrators at various levels across the country report a low amount, or even nonexistent, number of women in their applicant pools.

There’s a reason for that, The Maine Monitor found: Women do not always apply for jobs, even when qualified, and find themselves unable to tap into their network of relationships in the same manner as men.

“It can be pretty intimidating to be part of a coaches’ group dominated by males and be one of the only females,” said Hasson, who has led South Portland, her alma mater, since 2013, including a Class AA runner-up finish in 2020.

The reasons for women not always applying for positions varied, The Maine Monitor found.

“Women are never taught how to network; men do this very well,” McGraw said. “(Men) use each other to get ahead and help each other succeed. Women don’t have that advantage. That’s something we could learn from men.”

If athletic directors truly want to be part of the change and grow the number of women head coaches, McGraw said, athletic directors should seek women for the jobs.

“You have to do your job and look for them,” she said. “There are plenty of qualified women out there who haven’t had the opportunity.”

The development of women as head coaches has begun in Maine.

The Women’s Basketball Coaches in Maine group, founded in 2020 by University of Maine Coach Amy Vachon, seeks to reverse the hiring trend and provide support to female basketball coaches statewide. More than 100 participated in a coaching clinic in September, a significant bump from attendance rates at other clinics.

The latest uptick in women basketball coaches may be a testament to the work Vachon’s group is doing.

“Athletic administrators in Maine are realizing that a qualified female coach can provide our youth with important role modeling that makes a tremendous impact,” said Dartmouth College women’s basketball coach Adrienne Shibles.

Shibles is in her first year at Dartmouth after 13 seasons at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, where she was the winningest coach in program history.

Several coaches told The Maine Monitor that they encourage women to pursue any coaching opportunity available, including at the sub-varsity level. Working at the sub-varsity level, several coaches noted, allows more women to be coaches and provides them an avenue to develop their coaching styles and build confidence to work their way up the ladder.

The sports industry is all about making connections, which is possible at any level. That’s something that South Portland’s Hasson backed up with statistics.

“I have a female (junior varsity) coach and two of our three middle-school team coaches are females,” said Hasson. “My staff has been primarily female over the 10 years I have been coaching and those coaches who have left have moved up … to college or high school varsity jobs. It is very important that athletic directors are encouraging this.”

Crockett concurred, and urged those at least considering coaching to become involved and help shape young ladies’ lives.

“Knowing the influence female coaches had on me, and the influence I hope to have on my teams, I hope other young women feel compelled to coach high school athletics and beyond,” said Crockett.

“It is also very important to expose girls at a very young age that they can coach,” said Vachon. “If you see it, you can do it. Teaching young girls that coaching is a career and one that can bring so much joy into your lives.”

Despite having great coaches while growing up and at Mount View High, Shibles never considered coaching could be a profession for someone like her – a woman — until she had her first woman as a coach at Bates College in Lewiston.

“Representation does matter, and we need more women and coaches of color on our sidelines,” Shibles said.

Some women have left coaching over a lack of work-family balances, or have passed on opportunities to climb the ladder.

“I do my best to help women schedule around their family lives, if at all possible,” said Robbins. Recently, Robbins tailored a schedule with one of her female lacrosse coaches who had a daughter playing on another team, allowing the coach to fulfill her coaching and parental duties.

After a break from coaching, Hasson returned when her youngest children were 4 and 2, and stressed that flexibility with coaches’ duties as coaches and mothers is important.

Tailoring the timing of practice schedules, building a great roster of assistant coaches able to occasionally lead a practice and even allowing coaches’ children at practice might open the door for more young females.

“If athletic directors are not willing to make scheduling adjustments, our female coaches who are also moms feel resentful over time because they simply cannot sacrifice family over coaching,” Robbins said.