Public housing helped bring an end to Linda Gallagher-Garcia’s three years of intermittent homelessness in her hometown of Presque Isle, Maine, in 2020. With $200 in secondhand furniture, she made the apartment feel like home for her and her dog, Tex.

But when she fell behind on her rent and was evicted two years later, the fact that she was in public housing made her future more dire: Maine public housing authorities’ rules bar evicted tenants from returning to government-subsidized units and from receiving other benefits that could help them relocate.

Gallagher-Garcia had moved back to her hometown in northern Maine in 2017 after her husband died. She was working as a home health aid and struggled to earn enough to afford a place to live; then, when she got COVID-19 and had to take time off from her job, she fell behind on her rent. The Presque Isle Housing Authority evicted her in 2022.

“I was sick,” she said. “It didn’t matter to them.” Citing confidentiality rules, the housing authority said it could not comment on her case.

Last spring, Maine lawmakers had a chance to help public housing tenants at risk of losing their homes when they created a fund to prevent evictions.

But instead of doing what nearby Massachusetts and Connecticut did, and making public housing tenants eligible for the program, Maine did the opposite and specifically excluded them. That left public housing residents — who are more likely than others to become homeless after eviction — ineligible for the aid.

Those who crafted the law said they didn’t realize people in public housing might need such help. Gallagher-Garcia’s story shows why they do.

She owed just $955 in back rent and utilities when she got her eviction notice — an amount the new eviction prevention program could have covered if it had been in place and if she had been living in a privately owned apartment. Instead, at age 59, Gallagher-Garcia checked into the local emergency shelter where she stayed for two years. In total, state and federal dollars paid about $55,000 for her to stay there.

Maine’s pilot eviction prevention program, called the Stable Home Fund, opened to applications in October. It provides eligible households with up to $800 a month for up to one year, with additional funds available to cover back rent.

The creators of the Stable Home Fund thought that public housing tenants already had enough aid. Public housing, which is funded with federal dollars, is supposed to be affordable for low-income families, the elderly and people with disabilities, with rent typically capped at 30% of household income.

Public housing tenants, however, can still struggle to afford rent and be evicted just like tenants in private apartments.

In fact, in 2023, Maine’s public housing authorities filed a disproportionately high share of eviction cases, according to an analysis of court data obtained by the Bangor Daily News and ProPublica. The eviction filing rate for public housing authorities was more than twice as high as the rate for all rental housing: 10 eviction filings per 100 units for public housing compared with four filings per 100 units for all rental housing.

The cause of most public housing eviction filings in Maine was nonpayment of rent, based on a separate review of court data collected by Pine Tree Legal Assistance, Maine’s largest legal aid group.

Because of public housing rules forbidding tenants from returning after an eviction, and because public housing tenants are generally poorer than other renters, both publicly and privately owned properties become out of reach. (By contrast, people who have been evicted from privately owned housing are still eligible to live in public housing.)

As a result, the consequence of being evicted from public housing “is almost certainly homelessness and extreme housing instability for already vulnerable families,” said Marie Claire Tran-Leung, director of the National Housing Law Project’s evictions initiative.

That homelessness comes with a financial cost to state and local governments. A 2009 Maine study found that governments spent about one-and-a-half times more in services for a homeless person in the six months before they were placed in subsidized housing and given supportive services than in the six months after.

Public housing gets excluded

Little is known about evictions in Maine, in part because the state’s paper-based court system makes it hard to obtain data.

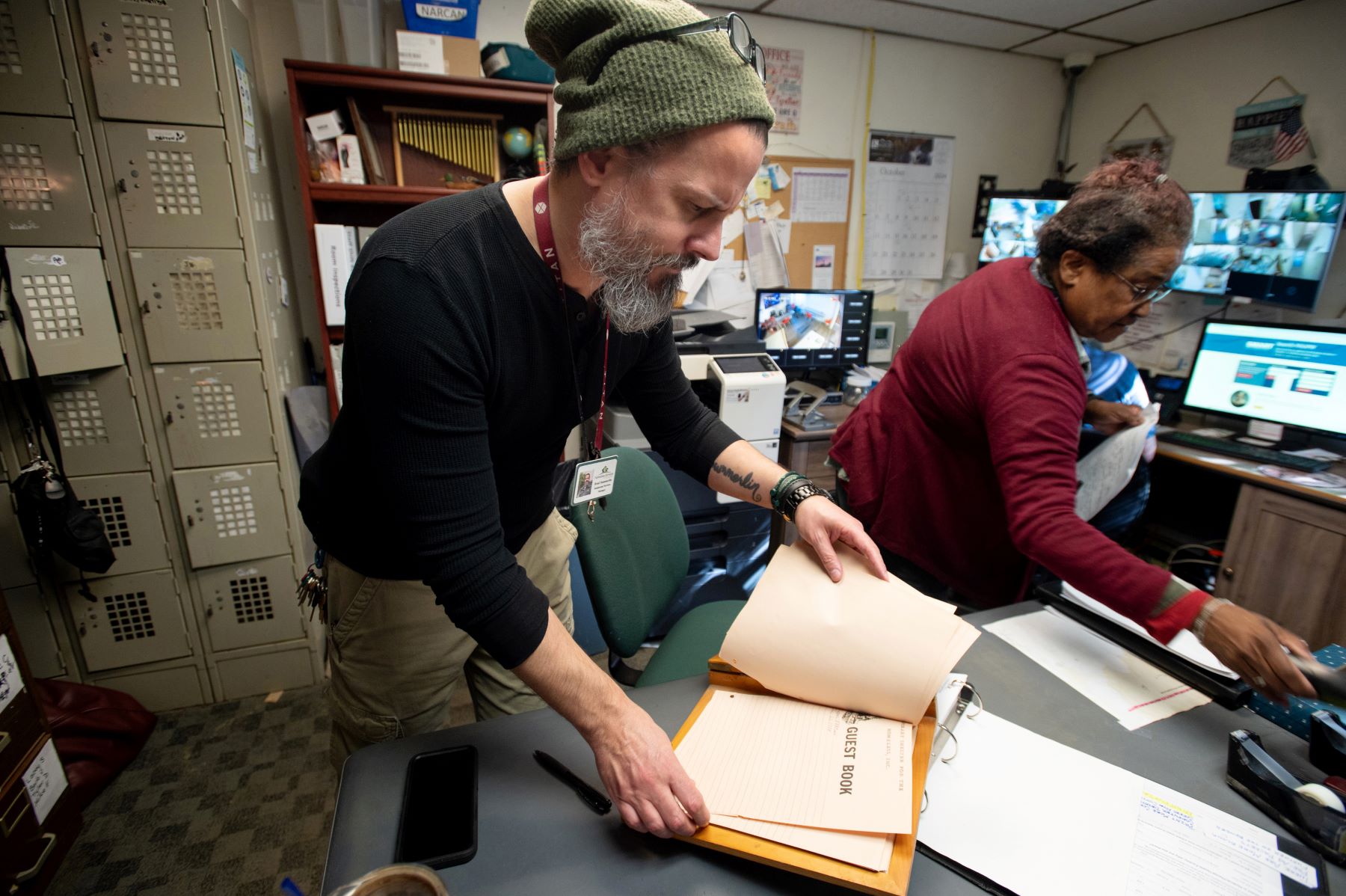

In 2023, Pine Tree Legal, a nonprofit that provides civil legal services to people with low incomes, spent a year traveling around the state to review eviction filings to understand why landlords try to remove tenants, how often renters don’t show up in court and how frequently they have representation.

The Bangor Daily News and ProPublica analyzed the data, which covered about 40% of cases filed between 2019 and 2022. The newsrooms also obtained further data from the state court system on every eviction case filed by a public housing authority from January 2019 through August 2024.

Taken together, the data provides a window into a little-noticed aspect of Maine’s housing crisis. Since 2019, public housing authorities, which had a combined total of 3,299 units last year, went to court to evict low-income tenants about 1,300 times.

In 2023, their cases made up 5% of all eviction filings, despite the authorities having just 2% of the state’s rental units. Of the public housing cases, three-quarters were in the rural 2nd Congressional District, which covers most of the state outside the populous southern coastal region and includes Gallagher-Garcia’s hometown of Presque Isle.

The Presque Isle Housing Authority, where she lived, is in the geographically largest county east of the Mississippi River and has a population of just 67,000 residents.

The housing authority filed nearly one eviction suit for every five of its public housing units in 2023, the highest rate of any housing authority in Maine, the Bangor Daily News and ProPublica found. The vast majority of cases in Presque Isle were for nonpayment of rent.

The housing authority said that a small minority of its cases resulted in actual eviction orders. (The state of Maine, however, does not track the number of people who leave after being threatened with eviction but before their cases are completed.)

The housing authority’s executive director, Jennifer Sweetser, explained that evictions are necessary because the agency’s budget relies on consistent rental payments. She also said that the housing authority doesn’t grant individual exceptions to eviction, which could be unfair or discriminatory. Instead, she said, the eviction process gives tenants a “neutral” way to resolve issues.

Farther south in the 2nd Congressional District, the Bangor housing authority filed more than twice as many eviction cases as the housing authority in Maine’s biggest city, Portland, located in the state’s other congressional district, even though Portland has many more public housing units.

This issue isn’t unique to Maine. Eviction Lab, a research organization based at Princeton University, has found that public housing authorities around the country use evictions as a rent collection tactic, sometimes at higher rates than private landlords.

Victoria Morales runs the Quality Housing Coalition, based in Portland, and was the architect of the eviction prevention program that launched this year. She said she didn’t know how often Maine public housing tenants faced eviction until the Bangor Daily News and ProPublica shared their findings, as her organization doesn’t usually work with people in public housing. “I think it is hard to see that this exists if you’re not in it,” Morales said.

Morales excluded tenants in public housing from the fund because she said their rent is already supposed to be affordable. The goal was to help people facing eviction who were not already receiving some type of aid, she said. (In the end, however, the program allowed renters to apply who were receiving other types of housing assistance — just not those living in public housing or who had a federal Section 8 voucher.)

The program’s cost to the state was also a factor in limiting who was eligible, said state Rep. Rebecca Millett, D-Cape Elizabeth, who sponsored the legislation that spurred the fund. “We had to get it through the appropriation process when we were competing with all the other really important needs that our state is facing,” Millett said.

Although Millett’s 2023 bill didn’t pass, a year later lawmakers decided to create and fund the rent relief program with $18 million through the supplemental budget process.

MaineHousing, a quasi-state agency that awarded a contract to Morales’ organization to run the program, estimated that 1,000 households could benefit over two years. In the first month, the program received 1,400 applications and had to start putting people on a waiting list.

Even with the high demand, two national housing experts said the Stable Home Fund could help more people if tenants of public housing could participate. That’s because monthly rent in public housing is much lower than on the private market.

Those experts said they don’t know of another eviction prevention program that excludes people in public housing. Kevin Connor, a spokesperson for the agency that runs Massachusetts’ program, said it is open to any household because the state wants to prevent homelessness, “whether they are in a house they own, an apartment they rent or a subsidized unit.”

Morales did not say whether she planned to advocate for public housing tenants to be included in the program in the future, but she said she would support the change if the state decided it was a priority.

Millett said she’d like to see the program expanded to help every Mainer who needs assistance, including people in public housing. But she will not be around when lawmakers convene in January; after 12 years in the Legislature, she didn’t run for reelection. Without Millett, and with no guarantee of future funding, the program’s longevity remains an open question.

Evicted from public housing

Public housing delivered Gallagher-Garcia from homelessness. But being evicted from public housing pitched her right back into it.

One cool day in April 2022, her nieces and nephews helped her empty out her apartment, throwing her furniture into a dumpster. “Basically, I didn’t have anything,” she said, in the same matter-of-fact way that she described many of the other challenges she’s faced, including battling cancer. When she checked into the shelter, it ended her longest period of housing stability since 2017.

She couldn’t move in with her sister, Nancy Gallagher, who also lives in the housing authority, because the authority bars people who have been evicted from staying with other residents. She had to stay near Presque Isle because that’s where her job was. So Gallagher-Garcia went to the shelter. “I just didn’t have time to find anywhere else to go,” she said.

Her dog, Tex, went to the kennel in Caribou, the next town up the road. Under the shelter’s rules, Gallagher-Garcia had to leave her metal crochet needles behind at her sister’s apartment because they could be used as weapons. She also was required to leave the shelter every morning; when she didn’t have to go to work or see a doctor, she spent the day in her sister’s living room calling around for apartments.

In her second year at the shelter, in 2023, her health started to decline — first a hernia, then ovarian cancer. With that diagnosis came more tests, surgeries and chemotherapy. “January, February, March, three months behind each other, not even giving my body time to heal or anything, one surgery after another,” she said. She made frequent trips to see specialists as far away as Portland, four and a half hours away.

Living in a room at the shelter with three to four women, she had little privacy when nurses came to check on her surgical wounds. When other residents started asking what was going on, she decided to tell them. “I didn’t sugarcoat it,” she said about her discussion with a boy in the shelter. “I said, you know, I could go to sleep and not wake up.”

In July 2023, she returned to work part time despite continued chemotherapy treatments, so she could save up enough to leave the shelter. She didn’t like sitting around, she said: “I wanted to go back to work and have something to do for myself.”

Finally, in June, after two years in the shelter, she moved into a motel. She was glad to have a quiet place to stay, and she got her dog back after paying a fee. But it cost $1,000 a month, twice as much as her apartment at the public housing complex. After about nine months, she fell behind on her rent, and the motel kicked her out, too, she said.

As of early December, Gallagher-Garcia was still at the local homeless shelter, looking for a place of her own. Every week, she said, she called landlords, looking for someone to accept her despite her financial struggles and prior evictions.

Then, she found something: a hotel room for $1,200 a month. That’s more than the last place, which she couldn’t afford. But she just turned 62, and now she can draw Social Security. Between that and her job, she hopes she can make it work.

This story by the Bangor Daily News was supported in part by a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

Bangor Daily News reporter Sawyer Loftus may be reached at moc.s1767225669wenyl1767225669iadro1767225669gnab@1767225669sutfo1767225669ls1767225669.

Have you been evicted from public housing in Maine, or do you know someone who has been? Please share details here.