Babies withdrawing from opiates. Children watching their parents shoot up heroin. Orphans growing up in foster care.

They are the opioid epidemic’s youngest victims.

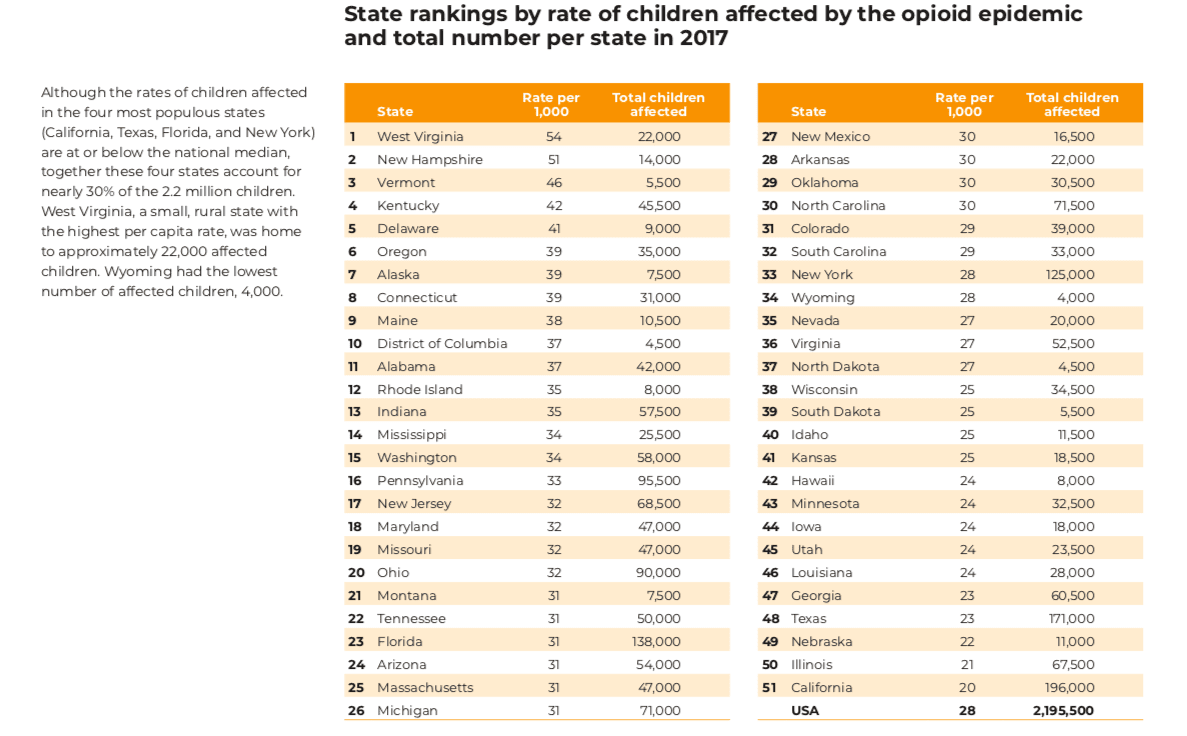

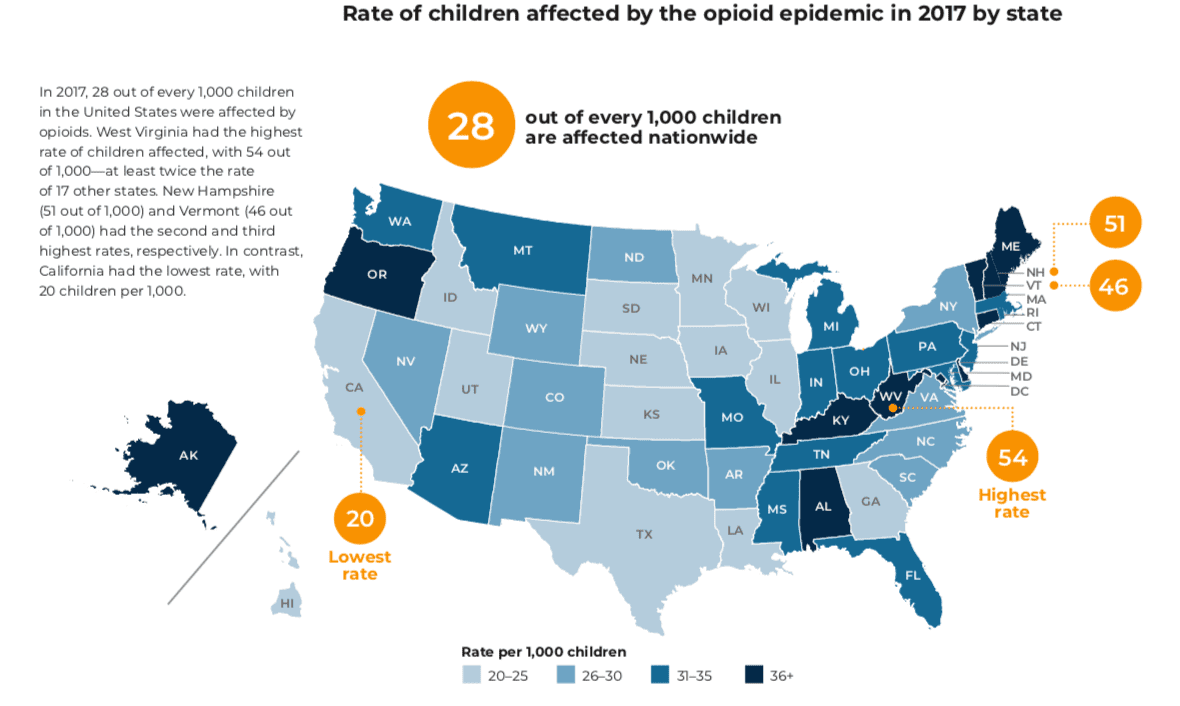

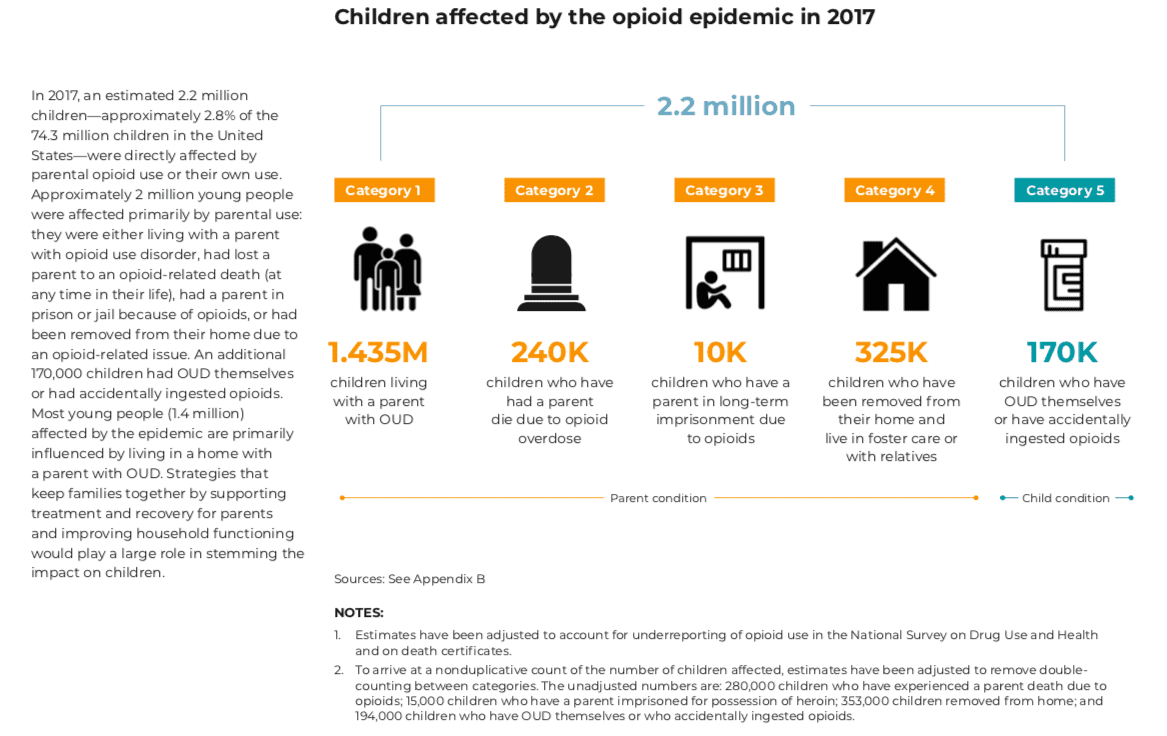

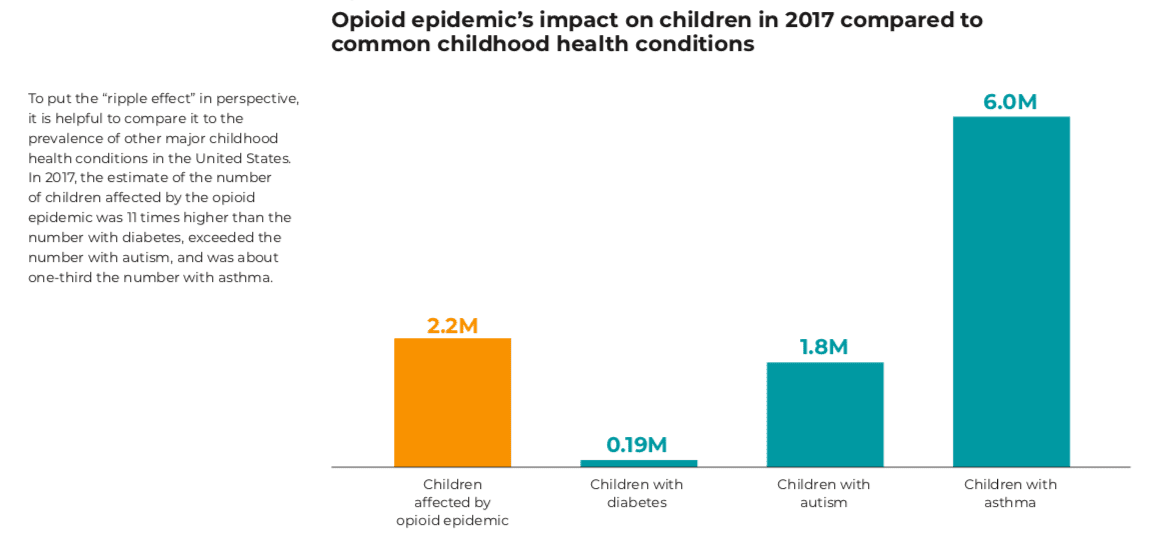

Nationally, an estimated 2.2 million children and adolescents were in crisis as of 2017 — 28 out of every 1,000.

According to The Ripple Effect, a report released today by United Hospital Fund (UHF) and the Boston Consulting Group, these children had a parent with opioid use disorder or had the disorder themselves.

The report noted the impact on children in each state in 2017. West Virginia had the highest rate, with 54 out of every 1,000 children affected.

Maine was ranked ninth, with 38 per 1,000 children affected, with a total of 10,500 impacted in 2017.

If current trends continue, the study noted, the number of children affected nationally by opioid use will nearly double from 2.2 million in 2017 to an estimated 4.3 million by 2030.

The cumulative lifetime financial toll — in health care, special education, child welfare and criminal justice costs — will soar from $180 billion in 2017 to $400 billion in 2030. Maine would incur an estimated $2 billion in costs in 2030.

“This report shines a light on a population affected by opioids that is often hidden from view,” said study co-author Suzanne Brundage, director of UHF’s Children’s Health Initiative. “But these estimates should not cause despair. Instead, they highlight the urgent need to take action now to help these children and their families.”

The report — also authored by Carol Levine, director of the United Hospital Fund’s Families and Health Care Project — also found that, without treatment, children affected by the opioid epidemic face increased physical and mental health problems, learning challenges, and a greater chance of developing an opioid dependency themselves. They are also likely to end up in foster care and the criminal justice system.

While the nation’s opiate overdoses have dominated the headlines, the devastating and long-lasting effects of the epidemic on children has received little attention, said Brundage.

“When talking about the opiate epidemic, traditionally it’s been about a narrow set of people affected,” Brundage said in a phone interview with The Maine Monitor. “We are urging policy makers, doctors and people in the community to take a broader look at this epidemic that is much more far reaching.

The task of helping the nation’s 2.2 million children affected by the epidemic is daunting, Brundage said, but there are treatment programs and steps that communities, states and the country can take.

“Decades of science have shown us that children can overcome a lot of adversity in the early years of their lives,” Brundage said. “Kids are resilient, but we need to give them help along the way.”

If the trend continues unabated, Maine will face a rising toll in human and financial costs. Maine will need an estimated $2 billion in 2030 to treat and care for children traumatized by the opioid epidemic.

Investing more treatment for families and children is “not just the right thing to do in terms of the kids, but it’s the right strategic investment,” Brundage said. “We have to interrupt this trend right away to avoid those costs.”

Though Maine has made progress over the past year, increasing support and treatment for families, expanding Medicaid and making the overdose antidote Naloxone more accessible, it still has much more to do, according to Gordon Smith, Maine Director of Opioid Response.

“It’s going to take a while to address the epidemic effectively, but the governor has made it clear it is our priority,” said Smith, whose job was created in January by Gov. Janet Mills. “We are bringing together every resource available through private money, grants, foundations, federal money.”

At the top of the state’s list is reducing the number of drug-affected babies. Last fall, The Maine Monitor reported that Maine had one of the highest rates of opiate-affected babies in the country, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control. An average of 975 drug-dependent babies were born each year in the state – nearly three a day – between 2013 and 2017. Though the number decreased from 952 in 2017 to 904 in 2018, it still is unacceptable, Smith said.

“We’ve got to make these children and moms with opiate-use disorder our priority,” Smith said.

Created earlier this year, Maine’s Substance Exposed Infant Steering Committee meets monthly with Smith to discuss programs and priorities to help infants and their mothers. The group’s goals include increasing the number of residential treatment centers that will take both moms and children; expanding support for mothers before and after they give birth, along with educating women with substance-use disorders about long acting reversible contraceptives.

“We’re exploring a wide range of ideas to reduce our numbers of drug affected babies,” said Smith, noting that the infants are challenging Maine’s hospitals, treatment centers and foster care system. “Last year, a large number of these infants ended up in state custody, the highest amount we’ve had during the past five years.”

Last year, a large number of these infants ended up in state custody, the highest amount we’ve had during the past five years.”

— Gordon Smith, Maine Director of Opioid Response

If the Maine Department of Health and Human Services believes that it is not safe for a drug-affected baby to go home with its mother, the infant is placed in foster care or with relatives.

From July 1, 2018 through June 30, 2019, 1,322 Maine children entered state custody, a 42 percent increase from 928 the previous fiscal year, according to Maine DHHS. Some 21 percent of the children removed from the hospital or their homes during that time period were under the age of 1.

Courtney Allen understands what it’s like to lose custody of a child to the state. Now an activist in the recovery community and an honor student at the University of Maine at Augusta, Allen’s two sons were placed in foster care in 2015 while she sought treatment and counseling through drug court.

“The pain, the shame, and the guilt,” Allen remembers, “was excruciating.”

Her sons were also traumatized by the separation, Allen said, an event that is often not shared with a child’s school system.

Allen agreed that Maine’s children would benefit from a West Virginia program highlighted in The Ripple Effect Report. The “Handle With Care” program is a collaboration between law enforcement and the West Virginia school system.

Now used in several communities across the country, it ensures that all children exposed to trauma receive appropriate interventions so that their ability to succeed in school is not jeopardized. Officers at the scene of a drug overdose, arrest or child removal, notify the student’s school that the child has been at the scene of a police incident and should be “handled with care.”

Kayla Kalel, a University of Maine student in recovery and mother of a 16-month girl, feels fortunate that she never lost custody of her baby.

“I was lucky enough to come in recovery before having her,” explained Kalel, who used heroin and illicit prescription drugs. “A lot of cool things have happened to me in recovery, but one of the most beautiful things is that she’s never seen me under the influence.”

The Brewer chapter leader of the nationally recognized group, Young People in Recovery, Kalel has seen the effects of a child emotionally harmed in a custody case.

“DHS showed up at a house in my neighborhood; the mom had an active addiction and they came with three police officers to take the young girl,” said Kalel. “Then they took the girl to her dad’s house and realized the dad had been arrested a few days before.”

The police searched the dad and arrested him on drug charges, Kalel said.

“So now the girl is sitting in the back of a police car watching her dad get arrested, not knowing where she is going,” Kalel said. “It was so traumatizing for her.”

Though she understands that the state puts children in custody to keep them safe, “they need to know where they are taking a child before they show up at the door,” Kalel added. “It’s hard enough on these kids dealing with parents who have substance use disorders. We’ve got to do a better job.”

Along with minimizing the hardship on children, Allen believes Maine needs to create more residential treatment centers that keep families together. While working with Colby College on a project researching Maine women’s drug use and recovery, Allen has listened to several mothers talk about being isolated from their families as they seek treatment.

“There’s very few places that mom and kids can go in Maine,” Allen said. “I spoke to a mom weeks ago, who wanted to take her baby to a recovery house, but the place didn’t take children. Removing or separating children should be a last resort. We know families do better when they are together.”