Editor’s Note: The following story first appeared in The Maine Monitor’s free environmental newsletter, Climate Monitor, that is delivered to inboxes every Friday morning. Sign up for the free newsletter to get important environmental news by registering at this link.

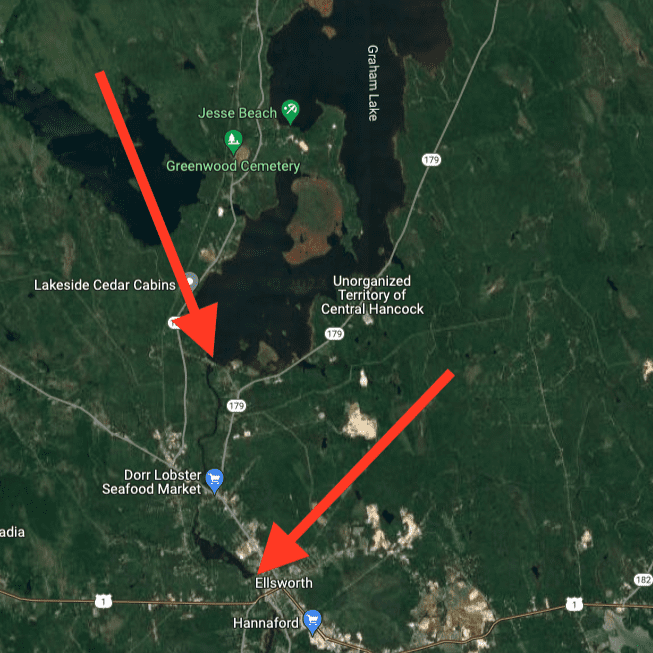

An eight-year fight over relicensing two Ellsworth dams owned by Brookfield Renewables will drag on at least a few months longer because of a backlog in the courts.

“The court system is so backed up that it’s going to be into April, May, June before the judge will look at this and determine if they’ll accept Brookfield’s argument,” Dwayne Shaw, Executive Director of the Downeast Salmon Federation, told a crowd that had gathered for an update on the case on Wednesday night in Ellsworth.

Brookfield filed the case in Kennebec Superior Court last year after being denied a crucial certification by the Maine Department of Environmental Protection, a decision that was upheld by the Board of Environmental Protection, a citizen board that oversees Department decisions. At issue in the case is the water classification standard of Leonard Lake, the body of water between the two dams.

Without the water quality certification, Brookfield cannot get a federal license to operate the dams. In a 2020 letter to The Ellsworth American, Tom Uncher, vice president of New England operations for the company, said the dams would be decommissioned if the license isn’t issued.

Like most dams, the case around the ones in Ellsworth is a complicated one, with a lot of competing interests. Advocates like Downeast Salmon Federation want to make it easier and safer for fish, including alewives and Atlantic Salmon, to pass the dams without getting killed. Brookfield wants to generate and sell electricity.

Homeowners who live on the shores of the lakes (which formed as a result of the dams being built more than a century ago) don’t want to live on mudflats. And state regulators want to make sure the water has the proper balance of oxygen and nutrients for all of the aquatic life in the lakes and river to thrive.

At the moment, most of those things aren’t happening, at least in the way anyone wants. Some fish make it through, but thousands are killed each year, a phenomenon repeatedly documented by Downeast Salmon Federation.

Brookfield says it has cut back on energy generation at certain times in order to allow for fish passage and manage drought. Homeowners are dragging kayaks through mud for hundreds of feet to reach the water. And state regulators say the aquatic life in the waters around the dams are showing “undisputed stress.”

“This is the big elephant in the room,” said Shaw on Wednesday. “It’s right in the middle of the city.”

Advocates insist that many of the problems could be solved if Brookfield put in a “gold standard” fish passage and stuck to a drawdown level of 2-3 feet, rather than the 5.7 feet the company requested in its water quality application. Shaw said that ideally, Downeast Salmon Federation would like to see the lower dam removed and the upper one kept in place. Removing the upper dam would be catastrophic for property owners along the shores of Graham Lake, which exists only because the upper dam is in place.

Brookfield, an asset management company based in Canada, owns dozens of hydroelectric projects in Maine, many of which it has acquired in the past decade. (Shaw said on Wednesday the company owns 90% of Maine’s hydroelectric generation; the Monitor was unable to confirm that figure before press time). Maine’s 51 licensed dams accounted for more than a quarter of the state’s electricity generation in 2022.

Brookfield also came under fire at another dam in Maine this week after several environmental groups accused it of violating the Endangered Species Act at the Milford Dam on the Penobscot River. Advocates say a fishway installed in 2014 isn’t working, and that neither the company nor the federal government have taken steps to fix the problem, according to reporting by Maine Public.

Brookfield is also in the midst of a fight over four dams on the Kennebec River, which advocates would like to see dismantled to allow for fish passage.

“What many of us are working on,” said Shaw on Wednesday night, “is trying to reconnect our rivers to the sea.”

Solar farm hits grid capacity

Another solar farm has bumped into a grid capacity problem — this one in Searsport, where New Hampshire-based ReWild Renewables has scaled back plans for a 5 megawatt solar farm to 1.2 megawatts, a fraction of its initial proposed size, according to reporting in the Belfast Republican Journal.

The Searsport proposal is the latest in a slew of energy projects attempting to connect to a grid that’s aging and undersized for our increasingly electrified world. Late last year, in Trenton, a man ran into a similar issue when he wanted to put up solar panels on his house and was told the grid was at capacity, according to The Ellsworth American.

Roughly 6% of homes in the United States have solar panels; that number is expected to grow to 15% by 2030. Solar accounts for about 5% of energy generation overall in the United States and roughly 3% in Maine.

“Really, Maine is looking at needing to invest in the grid and make some major upgrades in order for anymore solar to really happen in Maine,” ReWild’s Vice President of Project Development Joe Harrison told the Journal.

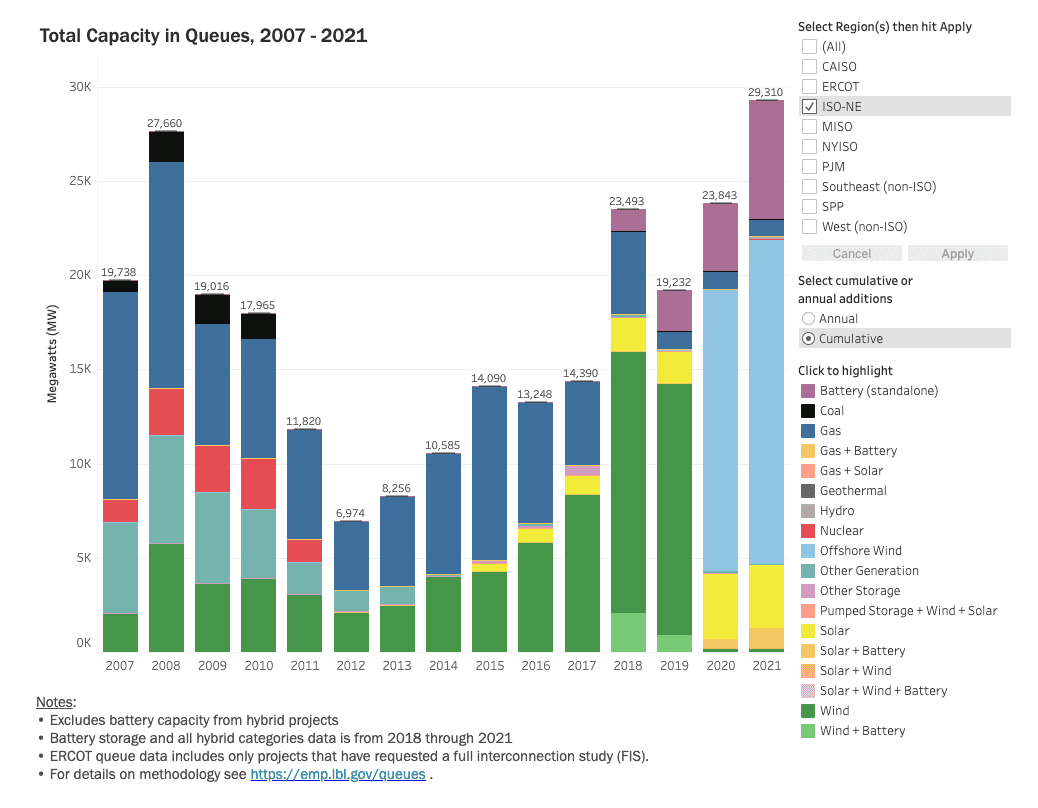

There were 8,100 energy projects waiting to connect to grids nationwide at the end of 2021, up 44% compared to the year before. In New England, most of the projects waiting in the wings were for offshore wind turbines, solar panels or standalone battery banks. This has clogged the interconnection queue and meant developers are now waiting an average of 4 years for approval, twice as long as a decade ago.

Most of these will never be built — between 2000 and 2016, only a quarter of proposed projects made it through the interconnection queue, according to research from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

“You can pass big, ambitious climate laws, but if you don’t pay attention to details like interconnection rules, you can quickly run into trouble,” David Gahl, executive director of the Solar and Storage Industries Institute, recently told The New York Times, referring to how lawmakers in Maine and Massachusetts offered generous incentives for small-scale solar installations but did not address the interconnection aspect in advance. “There’s a lesson there.”

Lawmakers are trying to fix the issue, and have directed the Maine Public Utilities Commission to undertake a grid planning process aimed at helping understand the state’s current infrastructure and looking at near-term investments that could be made to alleviate the backlog. (This recent Forbes piece discusses some of the challenges and possible solutions to the nation’s transmission line buildout problem, if you’re interested.)

“Hopefully undertaking that process should show what is actually happening on the ground,” Sen. Nicole Grohoski (D-Ellsworth) told The American. “Where does the grid need to be rebuilt and in what order.”

To read the full edition of this newsletter, see Climate Monitor: The Dam Fights Drag On & solar gets stuck.

Correction: A previous version of this newsletter contained a misleading statement. The federal government is responsible for enforcing the Endangered Species Act, not the state.

Kate Cough covers climate change and the environment for The Maine Monitor. Reach her with story ideas by email: gro.r1751320617otino1751320617menia1751320617meht@1751320617etak1751320617.