Maine has been a national innovator in the electoral process. This year, two of its favorite ideas — ranked choice voting and term limits — are coming up short.

Looking at Maine elections for governor for the last 100 years, the period between 1922 and 1970 produced races between a Republican and a Democrat with one of the two parties always the winner, even if there were at times a third candidate.

But that changed in the 1974 election, when independent James Longley, with 40% electoral support, defeated Democrat George Mitchell and Republican James Erwin. Mitchell had been forecast to win, but lost largely Democratic Androscoggin County, Longley’s home county.

Maine gubernatorial politics have never been the same. In the 1978 election, Democrat Joseph Brennan won thanks to the return of Androscoggin County, a third party candidate and Longley’s keeping his commitment to serve only one term.

In 1986, Republican John McKernan won his first term thanks to a four-person field. He took only 40% of the vote. In 1994, independent Angus King won with 35%, the lowest share ever. The field was split four ways.

Brennan and King would win outright re-election majorities, but no other winning candidate for governor between 1974 and 2018 would gain a simple majority victory. During the 2010 election, Republican Paul LePage edged past independent Eliot Cutler with Democrat Libby Mitchell trailing badly. LePage won just over 38% of the votes.

LePage won again four years later, with Cutler running third and denying Democrat Mike Michaud a victory. This time, LePage collected 48% of the votes.

The Democrats would not easily accept the two LePage minority victories. The logic was that the Democratic and Cutler votes amounted to an anti-LePage majority.

Ranked-choice voting, not used for statewide races anywhere else, could solve the problem. By allowing the third candidate’s votes to be reallocated to others, Cutler probably would have won, changing the entire political situation.

Maine adopted ranked-choice voting, but it did not matter. The Maine Constitution requires only a plurality vote for governor. The provision was adopted after the 1879 election when a post-vote fracas in Augusta over the election result almost produced an outright mini-war.

State elections would remain by plurality, immune from ranked choice voting, which would apply to federal elections and party primaries. Amending the Maine Constitution would be impossible.

In this year’s chapter of Maine’s gubernatorial election saga, the Republicans have turned again to LePage as their candidate for governor. This time he is not likely to face a divided field, partly because many Mainers do not want to give him the chance for another minority win.

Ranked choice voting is supposed to encourage independent and small party candidates to run. Their support need not be thrown away if they cannot win. But LePage, with a known and controversial record, is providing an incentive for third party candidates to back off being spoilers.

Being limited to plurality voting may not deter voters from forcing LePage into a two-person race. Experience may be a decent substitute for ranked choice voting. That could be LePage’s contribution to Maine’s electoral evolution. (Ranked choice voting has affected a Second District congressional race.)

Term limits fail

LePage is also involved with another state electoral innovation: term limits. The Maine Constitution prevents governors from serving three straight terms, but it does not prevent them taking a break and then running again. In effect, despite appearances, the Constitution does not set term limits on the governor.

George Washington invented executive term limits. He really wanted to leave the presidency after two terms. After Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected president four times, the Constitution was amended to provide: “No person shall be elected to the office of President more than twice…”

The Maine Constitution merely states: “The person who has served 2 consecutive popular elective 4-year terms of office as Governor shall be ineligible to succeed himself or herself.” LePage proposes to be the first former governor, after that provision was added, to serve two terms, take a break and try for a third.

Interestingly, the provision says the two-termer cannot succeed himself or herself. Isn’t that what LePage would do? Is the word “consecutively” meant to be understood?

The reason there is general agreement that he is not barred from a third term probably results from legislative term limits, which were adopted by referendum. A person is limited from serving more than four consecutive terms in each house.

Often, legislators swing back and forth in the State House. In the current Legislature, 23 of the 35 senators have also served in the House. Term limits have not produced a lot of new faces; only four senators are in their first terms.

The most interesting case is Rep. John Martin of Eagle Lake, who holds the record for lengthy service as House Speaker. Term limits probably grew out of his extremely long tenure. He is now finishing his fourth straight term in the House. He also served four terms in the Senate, preceded by many more years in the House.

LePage is providing the most obvious evidence of the failure of term limits. The voters wanted to prevent the growth of a permanent governing class. They did not succeed.

From time to time, the Legislature has considered repealing the law enacted by the voters. Recently, those efforts have abated. It may be that the legislators have learned the job is already done.

Maine’s split electoral vote

Another Maine electoral innovation is not in play this year. It is the manner in which Maine apportions its electoral votes for president.

Each state receives a number of presidential electors that is the sum of the number of its senators (two per state) and of its House members. D.C. also gets three electors. Most states conduct a statewide election and attribute all of their electoral votes to the state’s popular vote winner. The presidential election is treated like a series of state elections.

Maine has two congressional districts. It attributes two electoral votes to the statewide winner and then allocates each district one vote for its own popular vote winner. In 2020, Democrat Joe Biden got three votes and Republican Donald Trump received one from the Second District. (Republican-dominated Nebraska follows the Maine approach and gave one of its five votes to Biden.)

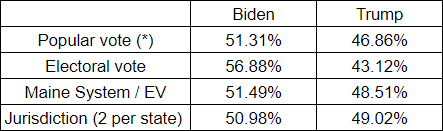

One way to test the value of the Maine system is to see what would happen if it were applied nationally instead of the winner-take-all approach used in 48 states and D.C.

A Maine voter counts more under the current system of electoral votes, but less than it would if its system were applied in all states. The Maine system comes close to the popular vote, which yields less influence for Maine than does the Electoral College, though either is less than one percent.

Two conclusions emerge on Maine presidential voting. Its system has benefitted the Republican candidate. And the system may disappear in 10 years, if the next U.S. Census allots Maine only one seat in the House.