The Maine company that recently launched the world’s first bio-fueled commercial rocket with a payload has just three full-time employees. Only two are drawing a salary.

Sascha Deri, the CEO, is not one of them. And he’s OK with that.

In fact, Deri still works as CEO of a company in Boxborough, Mass., called the altE Store, which is a solar energy equipment supplier. But he’s moved back to Maine to pursue his other passion as CEO of bluShift Aerospace, the Brunswick-based company that successfully launched and landed a bio-fueled rocket in Aroostook County on Jan. 31.

“My passion and curiosity lies with the earth up to the stars,” said Deri, 49.

It’s the beginning of the fulfillment of a dream that started from age 4, when Deri wanted to be an astronaut. Growing up in Orland and Bucksport, he enjoyed the woods, water and “the ocean of stars and vastness above.”

“When you live in a rural state, your mind is given more time to wander and wonder,” he said. “We can see the sky at night. You can see the stars.”

After receiving a physics degree in 1993 from Earlham College in Richmond, Ind., Deri wanted to get a job in Maine. He couldn’t find one, so he enrolled at the University of Southern Maine and earned an additional bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering. He had multiple job offers in Massachusetts, so for the next 20 years he built a career there before moving back in 2016.

He hopes to hire 40 to 50 people in the next five years to create opportunities for high-paying aerospace jobs so others who have moved away also can return.

“Many leave and never make Maine their home again,” he told lawmakers last March when he testified on a bill to create a governing body for a planned space complex. “Not because they don’t love Maine but because they can’t find the high-tech jobs they seek. We’re going to change that trend.”

For start-up funds, Deri and others on his team of eight who regularly work on the project put up $500,000 of their own money. For grant money, they received $139,000 from NASA and nearly $200,000 from the Maine Technology Institute to get the project off the ground, Deri said.

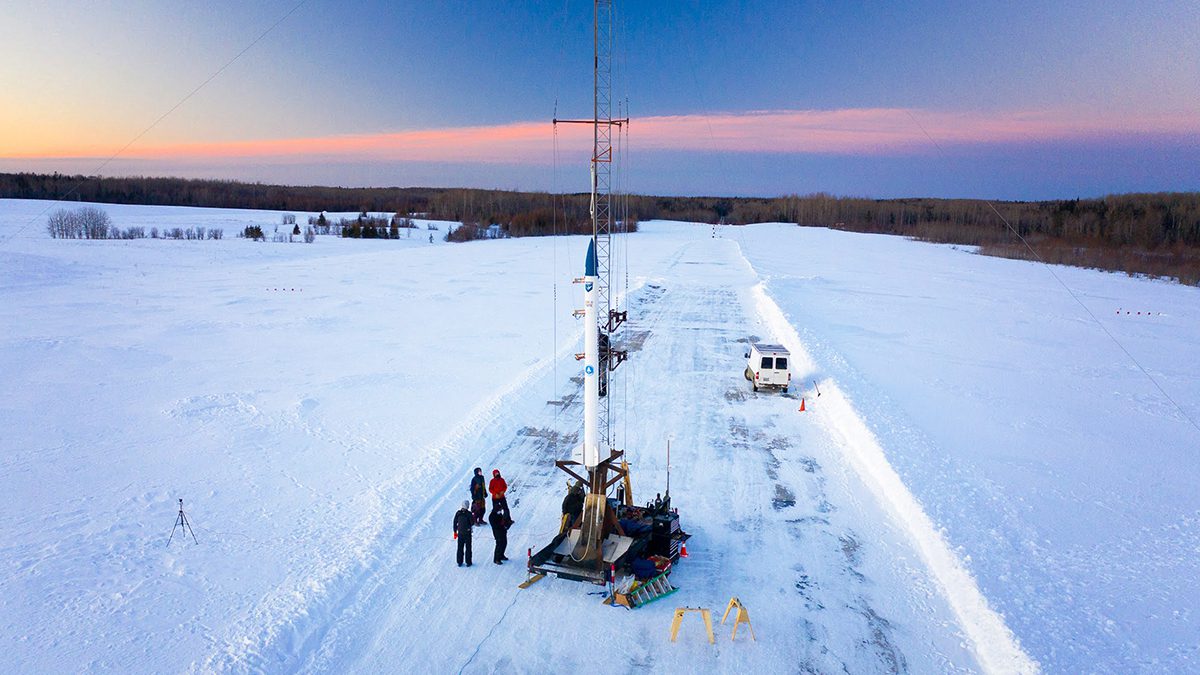

The Jan. 31 rocket launch in Limestone at the former Loring Air Force Base is part of an effort to convince investors that the company can be successful, he said. Just two days after the launch, Deri said he had about 200 emails from people expressing interest in the company.

“I did not expect that,” he said.

Brian Whitney, president of the Maine Technology Institute, said he expected investors to be impressed — and potentially interested — following the launch.

“We are absolutely thrilled that they successfully launched their Stardust 1.0 prototype rocket in Limestone on Sunday, utilizing their environmentally friendly, bio-derived fuel, and we are optimistic that it will lead to significant interest from investors,” he said via email.

Whitney and others, including the Maine Space Grant Consortium, are bullish on the possibility that bluShift Aerospace will be part of a larger effort to bring more high-tech jobs and companies to Maine. In 2018, the consortium, supported by a $50,000 grant from MTI, studied the possible economic impact of building a “spaceport” that would attract businesses that support what Whitney described as “the growing nanosatellite market.”

That market – which California-based growth consultants Frost & Sullivan estimates will be a $69 billion global market over the next 10 years – serves communications companies, scientists and academics by giving them an opportunity to launch their technology or experiment into space without having to wait for a big launch, Deri said. His company will charge the companies or academics to carry their payload into space, albeit an orbit much lower than traditional satellites.

SpacePort Maine, as outlined in the 2018 study, envisions a launch complex at the Loring Commerce Center in Limestone and a Mission Control Complex at Brunswick Landing, formerly the Brunswick Naval Air Station. In addition to creating jobs, the hope is to engage the public.

“In the short term, there will be viewing areas and opportunities for the public to be present during spacecraft integration and launch,” the report states. “Longer term, dedicated facilities will be constructed with more hands-on, interactive activities and a museum of some of our early successes.”

If that seems far-fetched, it’s worth noting there are already 10 spaceports in the U.S., according to the study. The closest to Maine is the Mid-Atlantic Regional Spaceport in Wallops Island, Va.

Deri said Maine is particularly well suited to launch into what’s known as the polar orbit. Instead of having a satellite orbit along the equator, those in the polar orbit travel between the north and south poles, he said.

Deri said a little over half of the companies he will likely work with want the polar orbit and some don’t care which orbit they are in. About half the market is in the communications industry — such as satellite TV — while many academics want to study climate change. The small satellites can also help study weather patterns or aid in the defense industry, he said.

While Deri has been quoted saying he wants to be the “Uber for space,” his company will focus only on cargo, not passenger travel.

“If nothing else, I hope our launch … and company, in general, serves as inspiration for what we in Maine can do,” he said. “Just because nobody in Maine has done it before doesn’t mean we can’t do it. This is a fantastic time to do something bold in Maine.”

The bluShift Aerospace team made history with its successful rocket launch and our Chasing Maine series documents how launch day unfolded.

You can also learn more about the initial weather-delayed launch and how the aerospace company worked with high school students to include a special payload here.