Spreading like dandelion fluff, a “No Mow May” initiative to support bees and other pollinators is taking seed in Maine.

It began when two Rockland residents sent City Councilor Nathan Davis a New York Times photo essay about how this movement had swept Wisconsin in recent years. “This is something the people of Rockland could get behind,” he recalled thinking, and he was right. The council supported the resolve unanimously, and Rockland became Maine’s first “No Mow May” community.

“No Mow May,” launched in 2019 by the UK group Plantlife, seeks to give bees, moths, butterflies and other pollinators more foraging opportunities in spring when their food sources are limited. A study in Appleton, Wisconsin found three times the bee diversity and five times the bee abundance on unmown properties compared to nearby mown sites.

While not a pollinator crusader, Davis said he’s “always wished that lawns were more wild and natural,” and he hopes this effort might foster “discourse about human-created and human-tended landscapes that aren’t so antiseptic.”

Such discussion is desperately needed, given that roughly 40 percent of the world’s pollinators are highly threatened due to pesticides, habitat loss, climate change and diseases. Pollinator declines imperil not only the majority of human food crops but most natural ecosystems — where 90 percent of wild flowering plants rely on bees and other pollinators.

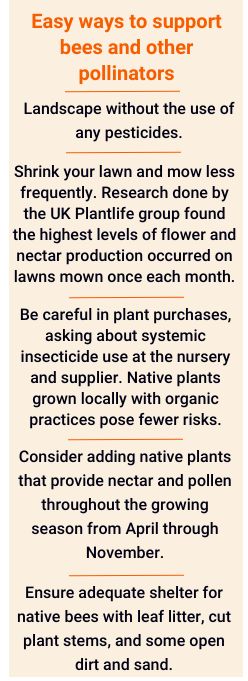

Eliminating pesticide use and mowing less frequently (a climate benefit in itself) are among many ways that Maine residents and communities could — in Robert McCloskey’s parlance — “make way for pollinators.”

Choosing the plants pollinators need

“No Mow May” challenges our cultural fixation with turf, the nation’s leading irrigated crop, which spans an area larger than Maine and New Hampshire combined. Rather than maintaining monoculture grass that primarily feeds Japanese beetles, what else might we do with our yards, parks and commercial landscapes that could benefit bees?

Start by considering ways to provide food, water, shelter and habitat, suggested Laurie Bowen, who co-directs University of Maine Cooperative Extension’s Pollinator Friendly Garden Certification Program. Planting flowers can be beneficial as a food source, but not just any blooms will do.

Hybridized flowers with features like double blooms don’t offer pollinators what they need. Insects have co-evolved for millennia with the plants native to this region and rely on these species for nectar and pollen. In Bowen’s words, “native plants are not engineered to please us but to please the pollinator.”

Spring wildflowers are just one way to provide support when food sources for bees are scarce. “We forget about the woody plants,” Bowen said. “They’re a very important source for pollinators, but they get overlooked.” Early-season bloomers like pussy willow, serviceberry and spicebush, and late-season bloomers like witch hazel, can be especially valuable.

Considering pollinators’ year-round needs

As for shelter, European honeybees favor communal hives, but most of the roughly 400 bees native to this region are solitary — nesting in plant stems, stone walls, open sand or dirt, wood or leaf litter. Many species of moths, butterflies and bees overwinter in leaf litter so vigorous fall cleanup regimes can destroy hibernating insects. Do pollinators, neighbors and the climate a favor by abandoning use of leaf blowers.

Letting some mown areas revert to meadow, with plants like aster and goldenrod, provides pollinators with the double benefit of late-season pollen and nectar and overwintering options.

Mow meadow areas just once annually in early spring, which gives birds access to seeds during lean winter months and creates future nesting sites for native bees in cut stems. Taller plants and leaf litter can foster tick habitat so consider mowing meadow borders and walking paths to minimize exposure.

Supporting larger-scale efforts

Fostering meadows and native plantings on city-owned land is already underway in Rockland, Davis said. The next step, he added, might involve changing an ordinance that limits lawn heights.

Maine communities could start adopting ordinances that encourage residents to landscape with native plants, measures already being passed elsewhere. Last year, Somerville, Mass. went a step further, passing an ordinance requiring that the city purchase between 50 and 100 percent native plants depending on the zone where planting occurs.

At prominent settings like Fort Williams Park in Cape Elizabeth and Marginal Way in Ogunquit, volunteers have helped to replace invasive species and turf grass with native plants.

Next up may be changing how public works departments and the state Department of Transportation manage roadsides to support pollinators, taking cues from a native species guide the DOT commissioned in 2016.

Maine took a significant step toward pollinator protection last year, passing a bill that prohibits most residential use of neonicotinoids, a group of insecticides particularly toxic to bees. As more states adopt similar legislation, use of systemic insecticides could decline.

With bees and other pollinators at risk, a cultural shift may be underway from highly managed and manicured landscaping to more ecological approaches. Naturalized settings hold innate appeal and value to a growing number of people who, with Davis, “like the idea of just letting more things be wild.”

Disclosure: The author serves as a contractual editor for the annual publication of Wild Seed Project, a Maine-based nonprofit that promotes native plants. Its free educational resources are cited in some hyperlinks and resources featured in this column.