In the past decade, eleven hospitals in Maine have announced plans to close their birthing units — four in just the past four months. Among the most recent were Mount Desert Island Hospital and Houlton Regional Hospital, whose closures were announced a week apart.

Northern Light Inland Hospital in Waterville paused its maternity services in February. MaineHealth Waldo Hospital in Belfast closed its labor and delivery unit on April 1. Houlton Regional Hospital will close its birthing unit on May 2; MDI Hospital will close its birthing unit on July 1.

The impending closures have drawn strong reactions. On Wednesday, more than 200 people gathered at a town hall in Houlton to share their concerns.

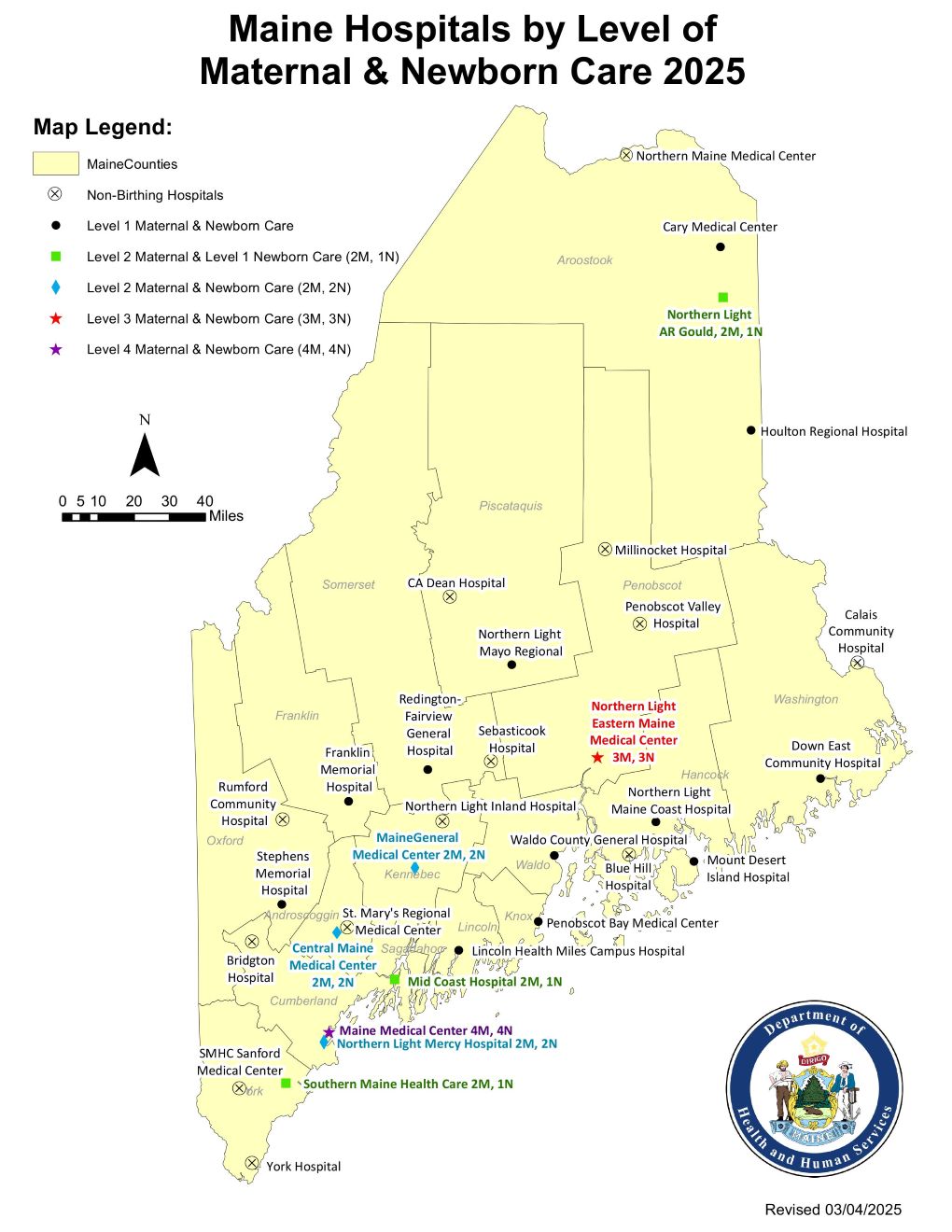

Hospital officials have attributed the closures to a steep decline in births. Today, more than half of Maine’s 36 hospitals no longer provide labor and delivery services.

This fits into a national trend. Between 2010 and 2022, more than 500 hospitals across the U.S. ended obstetric services, according to a December study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Rural Maine sees greatest impact

Although Maine’s closures span the state, rural Mainers are bearing the brunt. On average, patients in rural towns must drive 45 minutes one way to the nearest birthing hospital.

For those with high-risk pregnancies, accessing the necessary specialized care could mean traveling even further — to Bangor, Portland, or, in some cases, Boston.

As of April 1, Waldo County no longer has a birthing hospital. Washington County only has one birthing unit, located in Downeast Community Hospital.

With the upcoming closure of Houlton Regional in Aroostook County, large portions of northern Maine will be isolated from birthing units. Those living in Danforth, for instance, will be at least 90 minutes away from the nearest maternity wards in Presque Isle or Bangor.

Hospitals cite declining birth rates, staffing challenges

Hospital administrators cite several driving factors for these closures, noting that declining birth rates make running and maintaining obstetric units financially unsustainable, and that fewer births also limit opportunities for staff to retain critical skills.

Birthing units require a team that includes a surgeon and an OB-GYN who can perform C-sections, an anesthesiologist, nurses, and other staff — plus coverage for time off. Recruiting and retaining that team is especially challenging in rural communities.

Most OB-GYNs in the U.S. practice near large, urban medical centers. This is partly because research shows that physicians tend to stay within 100 miles of where they completed their training. Maine only has one obstetric residency program, which is located in Portland at Maine Medical Center.

Use of midwives on the rise

Hospitals statewide are increasing their use of nurse midwives — registered nurses with a master’s in nurse-midwifery — while home births attended by independent midwives are also on the rise.

Between 2018 and 2023, out-of-hospital births in Maine increased by 41 percent — from 228 to 321 — though hospital births still account for 97 percent of deliveries.

Independent midwives told The Monitor they are reluctant to attend home births without a nearby hospital as a safety net.

Increasing training, broadening staff among possible solutions

Hospital administrators told The Monitor that one potential solution to these closures could be expanding opportunities for OB-GYNs to train and practice in rural communities.

Experts also suggested cross-training nurses outside of the obstetrics unit or sharing personnel between hospitals within the same system.

Another idea they cited was allowing highly trained staff and nurse midwives to manage routine deliveries, only bringing in physicians for complicated cases and C-sections.

Some providers also suggested increasing access to independent midwives. In many European countries, for instance, midwives are more prevalent and often integrated into the hospital system — supported by standardized training and universal health care. In contrast, midwifery training in the U.S. varies widely, and most midwives work independently from hospitals.

Malpractice insurance costs make it difficult for many to operate outside of large health care systems, limiting their ability to fill the growing care gap in rural areas.