This article is part of U.S. Democracy Day, a nationwide collaborative on Sept. 15, the International Day of Democracy, in which news organizations cover how democracy works and the threats it faces. To learn more, visit usdemocracyday.org.

As the notion that elections are rigged has taken hold among a subset of Americans, spurred in large part by former president Donald Trump’s refusal to admit he lost in 2020, the processes that have long been central to U.S. democracy have come under scrutiny, and the work done by local government officials responsible for administering elections has become increasingly fraught.

More than a third of local election officials across the United States have been threatened, harassed or abused for doing their jobs, according to a survey conducted by the Brennan Center for Justice earlier this year.

“I think we’re in a really troubling moment, an inflection point in our nation’s history because there is — and make no mistake, it’s a minority — but it is a small, well-funded, well-organized, very loud faction of individuals seeking to leverage threats of violence and stoking fears to try to upend our democracy,” Maine Secretary of State Shenna Bellows said in a podcast with the Bipartisan Policy Center this summer.

In 2022, following an uptick in threats against election officials across the country, the Maine legislature passed a law that strengthened protections for election workers and mandated that threats be reported.

“Maine’s elections are some of the best run in the country, and that’s true in no small part because of the hard work and dedication of our local election clerks,” Bellows said at the time. “Protecting our town and city clerks from intimidation or violence protects our elections.”

The secretary of state’s office now offers regular training sessions to teach town clerks de-escalation techniques, something that would have been “unfathomable just a decade ago,” Bellows noted in the podcast.

The increasingly polarized climate has made it harder for election administrators to do their jobs and has even pushed some out of the field.

“Unfortunately, what you see is it’s led across the country to retirements of some clerks. People have left the field. It’s made it harder, in some circumstances, to recruit people to want to run our elections. And it’s definitely added another element of stress on a job that quite frankly is very rewarding, but also can be pretty high stress,” Bellows said.

In Maine, municipal clerks play a critical role in administering elections. This summer, between the June state primary and the November general election, The Maine Monitor sat with town clerks across the state — from York to Caribou — to ask about their work safeguarding the right to vote in a changing political climate.

YORK — To Lynn Osgood, an eleventh-generation Mainer, working as the town clerk and tax collector in York is “not a job, it’s a life.”

Wherever she goes, she expects to get questions: about car registrations, dog licenses, beach permits — and increasingly, elections.

“I don’t go to Hannaford in my pajamas,” she said, letting out a laugh.

Before starting in the clerk’s office, Osgood didn’t realize how many responsibilities there were.

“I had no idea what it entailed,” she said. “I don’t think anyone does.”

And a big part of that is preparing for elections.

This summer, Osgood joined municipal clerks from across the state for a training session at the Augusta Civic Center, in which the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency led them through hypothetical scenarios.

“It was very eye-opening for me about how ill-prepared I am for an emergency at the polls,” she said. “I’ve been so focused on procedure and law, and making sure that, you know, I have the right signatures, I have the right forms, I’ve done the right process in the order that the secretary of state gives me to open the polls, to close the polls, to tally the (votes) — that it never even occurred to me that in an emergency the election must go on.”

Since then she has worked to put together an emergency plan that covers everything from a foreign substance in an absentee ballot to an active shooter, and has designated a secondary location should a fire or other disaster occur.

“I have a plan in place,” she said. “The training was amazing.”

While Osgood doesn’t think the political climate in York has become as polarized as elsewhere in the country, she thinks she gets asked more about the voting process than her predecessor did.

“I pride myself on being completely transparent with the whole process. I welcome anyone to come in and ask questions, to see how we do things, why we do things, how we assure the integrity of the election,” she said.

Earlier this year, Osgood said she was invited to speak on the subject at a local Republican committee meeting.

“It was a wonderful opportunity for me to be able to answer questions because they had questions, and they asked the questions, and I answered the questions the best I could. And I was just very honored that they gave me that opportunity,” she said.

One question was about signatures on absentee ballot envelopes and how they are verified, particularly if someone requests an absentee ballot over the phone. She explained that in the software she uses, there’s a “display signature” button to check what’s on the absentee ballot envelope against what’s in the state’s system.

Attendees also asked about voting machines and whether they were at risk of being hacked. She explained the tabulators are not connected to the internet, and are running on software the Secretary of State’s office provides via thumb drive.

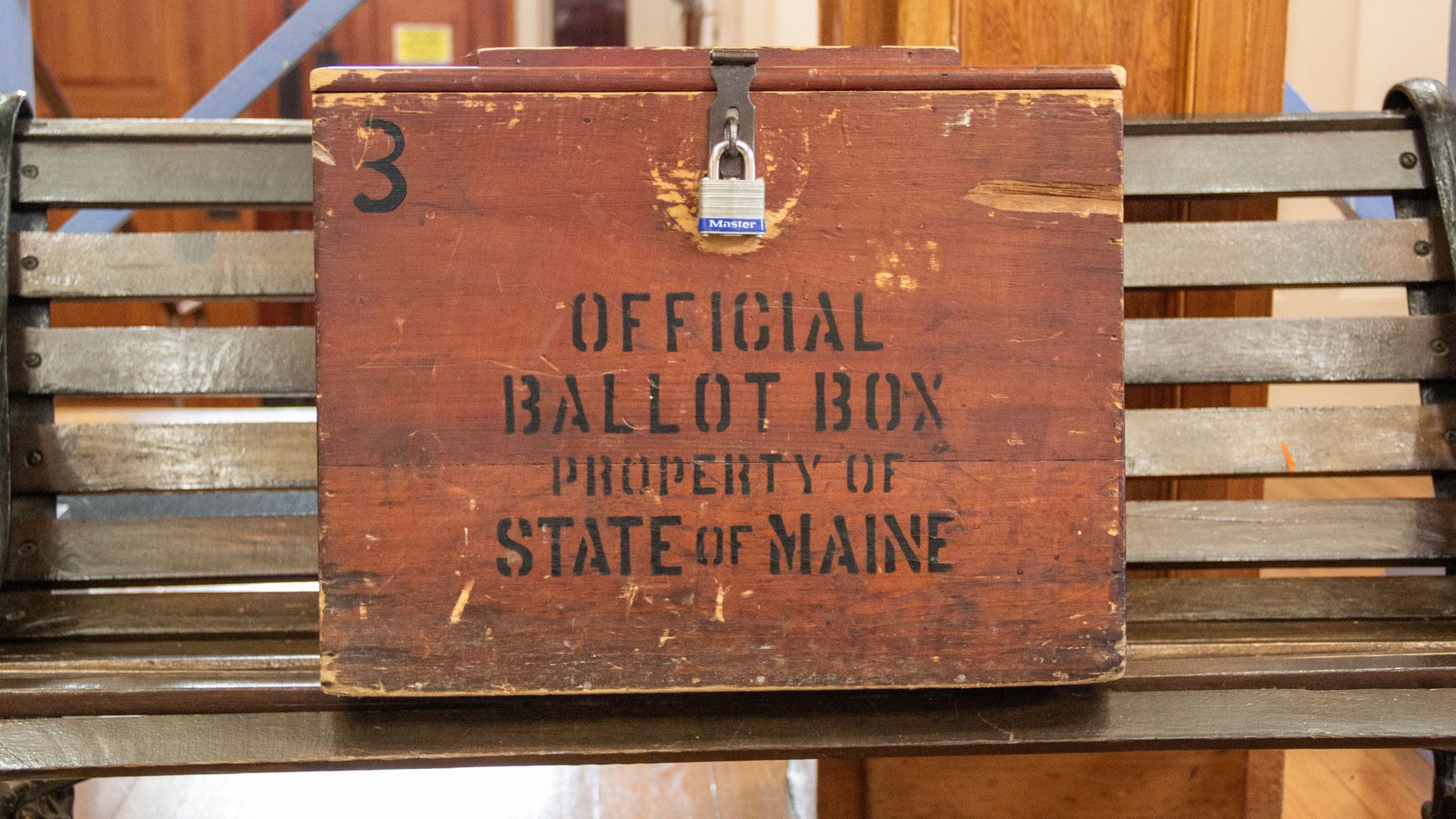

Another question was about whether the ballot box outside the town hall was secure.

“And I explained to them, you know, it’s on video surveillance from the police department 24/7. I’m the only one with the key, and when we go out to get ballots it’s two people at all times. There’s a ballot log that we fill out every time we open that box: who took the ballots out, who witnessed the ballots being taken out,” she said. “So that reassured them there.”

Osgood said it was a long presentation, and the attendees seemed largely mollified.

“I felt listened to,” she said. “And I feel like they got the answers they were looking for.”

GREENVILLE — When voters approach Greenville’s town clerk with sensitive questions, like how to navigate Maine’s new semi-open primary law, they’re likely to hear a reassuring phrase.

“Tammy Firman is Switzerland,” said Firman, who’s held the position for two years now. “I’m neutral.”

The law that went into effect ahead of primaries this past June allows Maine voters who are unenrolled to select either a Republican, Democratic or Green Independent ballot, voting only in whichever primary they choose.

That process has election officials like Firman more intimately involved in the partisan side of politics, which, paired with growing mistrust in election officials, has some people on edge, Firman said.

She sees it as her obligation to reassure them of her objectivity and independence.

“I respect whatever you believe,” Firman said. “We want you to be able to exercise those things without feeling any pressure from us one way or the other.”

Firman and her husband visited the Greenville area for decades, traveling from their home near Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains. Shortly after the couple retired in 2022 and moved to Greenville permanently, Firman saw a sign in the town office advertising for the town clerk position.

Firman, who spent her career as a registered nurse, didn’t expect to get as far as an interview but applied because she wanted to give back to a community she’s long admired.

“They must have been desperate because they hired me,” Firman joked.

This November will be Firman’s first presidential election, but she feels confident because she has the guidance of the town’s longtime deputy clerk, Bethany Young, and a capable cast of experienced poll workers.

More than anything, Firman is looking forward to seeing the increased voter turnout that typically comes with presidential elections.

It’s that type of civic engagement that drew Firman to the position in the first place, and she’s excited to see it reciprocated, even if there’s added stress in making sure the tabulation process is followed precisely.

“We really, really go the extra mile to make sure we’re doing everything exactly as we’re supposed to because I don’t want there to be any question in anybody’s mind that we’re doing anything malicious or not right,” Firman said.

“At the end of the day, I know we have done the best we can, and I feel good about that.”

TURNER — For the better part of the past two decades, Rebecca Allaire has helped run Turner’s town business as town clerk, tax collector and treasurer, overseeing everything from elections to tax liens and foreclosures to town payroll.

A lot of work goes into making sure elections are secure and everyone’s vote is counted properly, Allaire said. But distrust in elections has grown, something she sees as perpetrated by the media.

“People just don’t know the process,” she said.

A few years ago, for example, a person came into the town offices every day during early voting. It’s well within their rights to observe the voting process, Allaire said, but this person kept berating election clerks for not telling voters one thing or another. (At least two election clerks — one from each of the major political parties — are appointed to serve at each voting place, and provide checks and balances during the process.)

Allaire said that once a ballot is handed to a voter, an election clerk cannot answer any questions about the candidates because that could be seen as swaying a voter’s choice.

The same person called the Secretary of State’s office multiple times about the ballot drop box outside town offices. The office investigated and found the ballot box was properly mounted to the wall, locked and tamper-proof. It was deemed secure.

“We were doing everything that we were supposed to do,” Allaire said. “It’s gotten out of control, honestly.”

Making sure elections are secure and everyone’s vote is counted properly all starts far in advance of election day, when Allaire hands out nomination papers for local candidates and confirms that every signature on the returned petitions belongs to a registered voter in town.

Clerks must account for every ballot sent out for absentee voting. Returned ballots are kept in a sealed box in a vault.

Counting absentee ballots takes three or four people — one person checks off the name on the envelope on voter rolls, another opens the envelope and the last person feeds the ballot into the voting machine — so everyone’s vote is kept confidential.

Allaire must end election day with the same amount of ballots as the start.

The tenor of the election usually depends on who the candidates are, Allaire said. She’s worried this upcoming election will be the worst when it comes to rigged election conspiracies.

“It’s very, very difficult — almost impossible to (rig elections) in the state of Maine because of all the precautions that the secretary of state has in place,” said Allaire.

Allaire said she treats everyone with the same respect. Their feelings are valid, she said, so when someone comes in with a question about election security, she takes the time to explain it to them. Most of the time, that quells their concerns.

“I get it. I can understand, you know, (with an) absentee ballot how do they know that I’m not opening it up here in the office and reading it to the girls and saying, ‘Oh look who Suzie voted for, can you believe that?’” she said. “I mean, I understand why they would think that until they know, you know, I’m accountable for those.”

HALLOWELL — Lisa Gilliam, the Hallowell city clerk, said she first noticed a shift in attitude toward elections eight years ago, in the run-up to the 2016 presidential election.

Gilliam, now in her 30th year serving in municipal government, was just 24 when she began her career as a deputy clerk in Winthrop. It was September, she remembers, and the 1994 gubernatorial election was just a couple of months away.

“I was so stressed out,” said Gilliam, now the clerk for Hallowell, a city of about 2,600 in Kennebec County.

She took the required election training from the secretary of state’s office. The deputy secretary of state even gave Gilliam her personal phone number.

“They made sure that I got through it and survived,” she said.

About two years later, Gilliam was promoted to town clerk in Winthrop, where she spent nearly 18 years. For many years, elections were relatively “laid back,” and even fun, a chance to see people from around town that maybe she hadn’t seen in a couple of years, and work with election clerks, some of whom had been volunteering for years.

But that all changed in the run-up to the 2016 presidential election, Gilliam said. At the time she was city clerk in Gardiner and that was the first time she said she noticed any tension surrounding elections.

“It was completely different,” before 2016, Gilliam said. “Now you feel like all eyes are on you.”

Clerks are the backbone of municipal government, and paramount among their responsibilities are running elections. Gilliam used to do it mostly without questions from residents. But over the past eight years, she said she’s been on the receiving end of a lot of anger from people “expressing their doubt” over the process.

COVID especially brought a lot of tension. Gilliam was working in Winslow in 2020, and one resident kept telling her he thought there was election fraud going on. So Gilliam asked him to be an election clerk.

“He was fantastic,” Gilliam said. “He was one of the best workers I had.”

At the end of the day, he came up to Gilliam and said, “I want you to know that I trust the process a lot more now that I’ve worked here.”

“That’s something that I will tell people, people that question it,” Gilliam said. “I encourage them to come and work with us on election day, and see what we do.”

CARIBOU — Danielle Brissette became a clerk after going into the Caribou municipal office to register a dog and a snowmobile.

That was five years ago, but Brissette said she still feels like a newbie. There have been eight other city clerks since Caribou was founded 214 years ago — including Brissette, that’s an average tenure of 24 years.

Her first presidential election as a city clerk was in 2020 when the pandemic was raging. Brissette said the focus then was much more on preventing the spread of disease. She had people assigned only to wiping down voting machines after each voter.

This year, Brissette said she’s more concerned about safety and security. Talking to The Maine Monitor shortly after an assassination attempt on former president and current candidate Donald Trump, Brissette said she was thinking about having a permanent police presence during election day, rather than occasional visits throughout the day.

“We didn’t have a lot of big talks about that (in 2020),” Brissette said. “Maybe it was just because I was so new and we were in the middle of a pandemic. That could be why I just didn’t recognize the danger of elections.”

Since then, Brissette has attended de-escalation trainings and done walkthroughs of the voting location (the town’s wellness center) to identify risks, and has established a second location where voters could move if necessary.

An active shooter is the worst-case scenario, she said, but it’s her duty to prepare for it. She has a readiness plan, which also accounts for the possibility of natural disasters or power outages. (Caribou’s voting location has a generator.)

While prepared for the risk of political violence, Brissette said she’s encountered very little animosity from her community regarding the election. Tensions may rise closer to November, she acknowledged, but so far she hasn’t felt a dramatic shift in the attitude of people coming into city hall.

If someone does try to confront her, Brissette said she refuses to engage in political discussions because of the importance of her nonpartisan position.

“If people question the process or anything, at the end of the night when the polls are closed, people are welcome to stay and watch,” she said. “It helps you to see the process and to learn it. And that’s the way it is across the state.”

The most common concern she hears is whether the voting machines are hooked up to the internet. Brissette answers that there is no way to hook them to the internet; the machines are programmed by the secretary of state’s office; and all machines are tested before the election.

Brissette anticipated a high turnout this year and thinks there is about the same amount of interest as in 2020. She predicts about 65 to 70 percent of Caribou’s 6,500 registered voters will go to the polls.

She said it’s important to remember it’s not only a presidential election. There are also referendum questions and local races.

“Election day: It’s safe, it’s secure,” she said. “And we’d love to see them come out and vote because their voice matters.”