Maine officials anticipate a modest turnout on June 14 for the state’s primary elections, though they are on heightened alert for threats against poll workers amid a growing cloud of misinformation about the security of Maine’s elections.

Secretary of State Shenna Bellows said there are layers of protections built into Maine’s election systems to ensure the accuracy of its count, down to the individual voter. As the state’s top election official, she is concerned by claims made locally and nationally that could erode public trust in Maine’s history of holding “free, fair and secure elections,” Bellows said.

“Unfortunately, one of the things that we have observed since the 2020 election is deliberate disinformation and misinformation being spread about elections nationally, including here in our state, designed to undermine voter confidence,” Bellows said. “What’s really tragic is disinformation and mal-information are fancy words for lies.”

There is no evidence of widespread voter fraud in Maine or elsewhere despite repeated claims by former President Donald Trump and Republican Party members that it occurred during the 2020 presidential election.

Claims of voter fraud or election security problems have been used by both major political parties throughout history, and currently most of the claims are coming from Republicans, said Mark Brewer, the University of Maine interim chair of the Department of Political Science.

“The Republican base, which still adamantly supports Trump, eats that stuff up and they believe it. So if you’re a Republican running for office in 2022 and you want to appeal to the base of your party and these adamant Trump supporters, you have to pay lip service to fraud,” Brewer said.

Yet claims that question the integrity of elections have the potential to be “incredibly damaging” to the public’s trust in democracy, Brewer said. At the same time, some politicians may try to tap into those fears because it energizes their voters and makes them participate in an election, he said.

An estimated 10 to 20 percent of voters are anticipated to cast primary ballots, Bellows said.

Maine has protections in its election process to ensure that only eligible people vote and only cast one ballot.

Chief among those protections is Maine’s use of paper ballots that are marked by the voter and not a machine, Bellows said. Prior to an election, the state tests the memory devices that are programmed to read ballots to ensure the machines used to count ballots — known as tabulators — produce the same results as a hand-count of test ballots. Clerks repeat those tests on local machines. Tabulators are not connected to the internet.

Local nonpartisan clerks then report each person’s voting history in the days following each election through the state’s central voter registration system. This allows state election officials to verify that the total number of ballots cast and voters match. It also lets election overseers check that voters did not cast multiple ballots either by voting by absentee ballot and again in-person, or at multiple polling locations.

The only cases of alleged voter fraud charged by the attorney general’s office after the 2020 election were against two University of Maine students. One case is still pending against a woman who allegedly voted twice. Two felony charges against another woman were dismissed in November 2021 after she completed 200 hours of community service and wrote an apology letter to a voter she falsely submitted an absentee ballot for, according to Danna Hayes, a spokeswoman for the Office of the Maine Attorney General.

“What the data shows is that the majority of people are honest, and that there are checks and balances at every step of the process to ensure only people who are duly registered in a municipality are casting a ballot and participating in an election. People who try to cheat by voting twice are caught and are prosecuted fully under the law,” Bellows said.

Partisan poll watchers are also allowed to observe inside polling locations on election days.

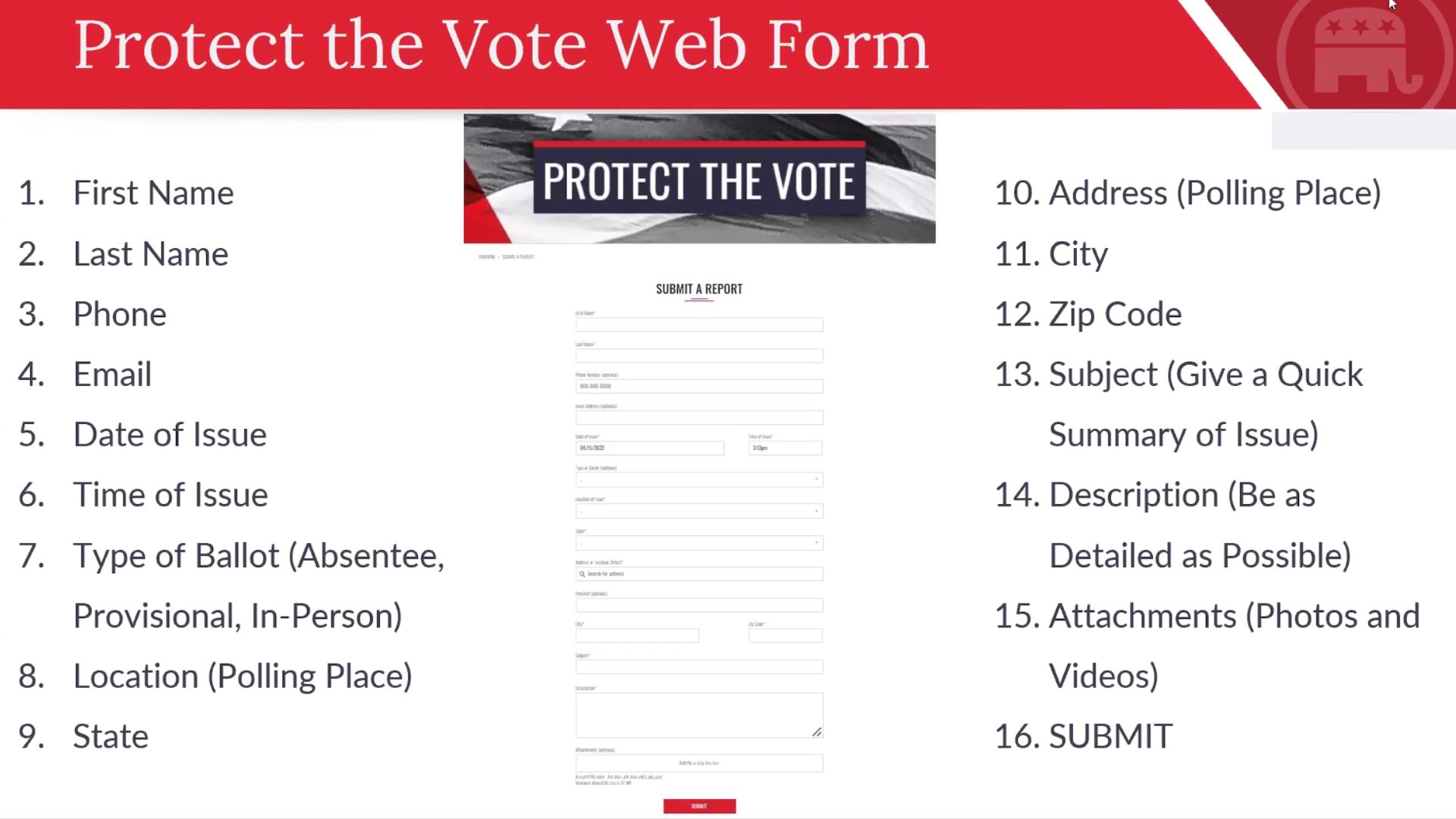

The Republican National Committee has hired Election Integrity directors in 19 states, including Maine, to do poll worker training. During a recent virtual training event, the Maine election integrity director, Sharon Bemis, reviewed how to challenge a voter and report irregularities — from late start times to malfunctioning tabulators — in real time with videos and photos through its “protect the vote” online form.

“In order for the democratic process to work, Americans must have confidence that our elections are free, fair, and transparent,” said Maine Republican National Committee spokesman Andrew Mahaleris. “In Maine and across the country, the RNC is committed to defending those principles.”

Voters do not need to show ID at their polling location, which has been criticized as a possible election security problem. But Bellows says it is not a threat because there’s a comprehensive voter registration process.

To appear on a voter list at a polling location, people must first prove their identity, citizenship and residency to register to vote, which is why the state is confident that non-citizens are not voting and people are not being bused in from other states to vote, Bellows said.

Paul LePage, the former governor and Republican gubernatorial candidate, has lobbed unfounded accusations that voters were bused in from Massachusetts to vote in state elections in 2009.

“If you’re going to make claims like that, in my view, you need to have some evidence to support them. If those things are really happening that’s obviously a huge problem, but if you’re going to make those claims you best have some evidence. Thus far, unless I’ve missed it, the former governor has produced zero evidence,” said Brewer, the political scientist.

LePage supports a “common sense” voter ID law, said Brent Littlefield, senior political advisor for the campaign. He pointed to testimony Bellows made to the state Legislature in April 2021 that 162,266 active Maine voters did not have a matching drivers license or state ID record.

“It only makes sense to most voters that we have an ID when you vote,” Littlefield said.

In response, Emily Cook, a spokeswoman for the Secretary of State, said some of those 162,266 voters actually may have ID. Cook said the figure was an estimate produced to help legislative staff determine the potential cost of a proposed bill.

When Maine implemented its first central voter registration system in 2007, it converted lists kept at the local level into a statewide system. Some of those lists did not include drivers license numbers though voters had demonstrated proof of identity another way. The state did not require voters to produce ID to remain a registered voter, Cook said.

Skepticism about your government is part of a healthy democracy, but it is corrosive when it is used to undermine systems and institutions, said Amy Fried, co-author of the book At War with Government: How Conservatives Weaponized Distrust from Goldwater to Trump, and a professor of political science at the University of Maine.

Fried co-authored a paper in October 2020 predicting likely impacts if Trump persisted in “delegitimizing the election,” and correctly foresaw that “initial vote counts would favor Trump but would become increasingly pro-Biden as mailed ballots are counted,” and that Trump would use that as a reason to claim the election “was being rigged or stolen.” They also correctly predicted that, “there is potential for not only protracted legal challenges, but also social disruption” after the election and before the inauguration — which manifested during the insurrection at the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021.

In states other than Maine, there are signs of some Republicans again trying to shape public opinion to reject election outcomes because of “fraud,” Fried said. It is not clear that this always benefits the candidate making the claim and may even suppress turnout.

Still, the Maine Secretary of State’s office is “on high alert” for violent threats and poll worker safety, Bellows said. The office is in contact with law enforcement to ensure they can intervene if there are problems at the polls, she said.

“It is something that we are concerned about because of trends across the country,” said Bellows, who referenced reporting by the news agency Reuters that documented more than 900 “threatening and hostile” messages sent to election administrators or staff in 17 states during the 2020 election.

“One clerk was sharing with me, at the polls, people used to come with pies and treats and hugs. And definitely for some clerks it’s a very different environment,” Bellows said.

Gov. Janet Mills signed a law passed by the legislature this year that improves de-escalation training for clerks and makes it a Class D misdemeanor to harass poll workers. Heightened public tension from recent elections has made some Maine clerks leave their jobs, and several towns and cities to hire clerks ahead of the primary election, The Maine Monitor reported.

The loss of experienced election workers willing to staff the polls will be a problem, Brewer said.

Brewer noted that understaffed municipal clerk offices and how that affects the administration of the state’s elections is a story the public should be watching. Results could take longer to be reported. New or inexperienced election workers may make innocent errors or oversights.

“Every time there’s a mistake that happens or a delay, that could very well, and I think would, reinforce beliefs among those that already think there’s something funky going on,” Brewer said.