On the first morning of spring, with temperatures hovering around freezing, a large flock of retirees descended like robins on a former farm field in Belfast, the site of a sprawling Bank of America office. They were greeting the new season with an urgent demand — that the bank stop funding fossil fuel projects, which endanger life on earth.

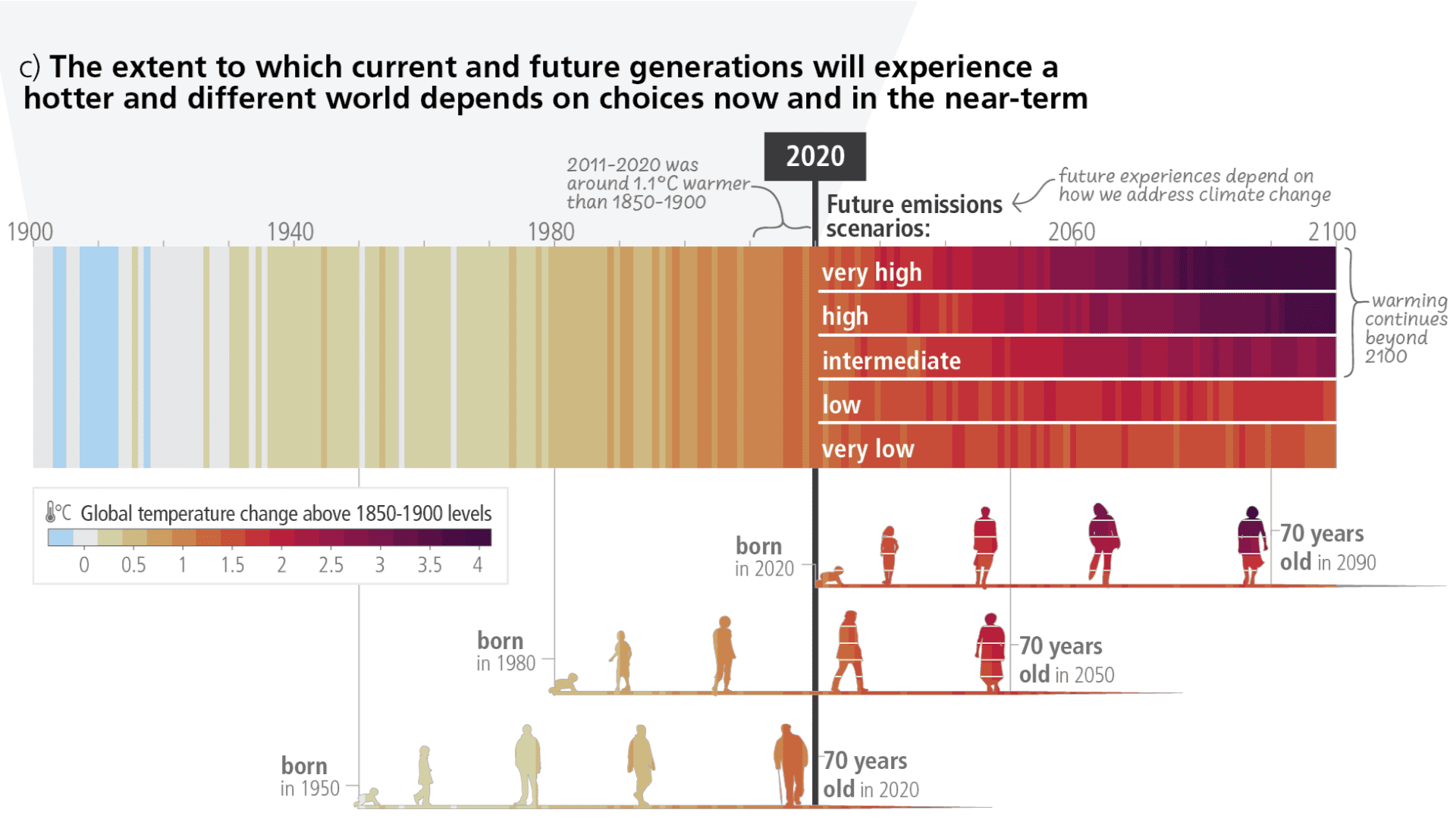

That language is not hyperbolic, an Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report last month confirmed. “There is a rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a livable and sustainable future for all,” the United Nations scientific body stated.

That shrinking window is down to about 27 seasons, what’s left of this decade. Every season that we delay, the prospects for our beleaguered planet dim.

To reverse course on global warming, we need to correct what one IPCC report author calls “misaligned finance,” the bankrolling of fossil fuels instead of clean energy. Bank of America, Chase, Citi and Wells Fargo all finance fossil fuel expansion, having collectively invested more than a trillion dollars since 2016. The Canadian bank TD is also a major fossil fuel funder. In contrast, Europe’s largest bank, HSBC, announced late last year that it would no longer finance new oil and gas fields.

The March 21 actions in Belfast and Portland, two of roughly 100 events nationwide, were organized by Third Act, a group founded by writer and climate activist Bill McKibben that seeks to mobilize the segment of Americans who hold roughly 70 percent of the nation’s personal wealth: those over age 60. The actions were part of a campaign urging Americans to transfer accounts to banks and credit cards that do not fund fossil fuels (see box).

The financial industry is a big part of what’s slowing the transition to clean energy “because (big) banks aren’t investing in the right things,” said Ridgely Fuller, a Third Act Maine coordinating committee member who helped organize the Belfast action. Transferring funds to regional institutions infuses more resources into the local economy, funds that could be used to accelerate adoption of heat pumps, solar panels and other measures to reduce fossil fuel dependency.

Acting on fears of climate chaos

Bank of America did not appear receptive to the message of planetary survival being carried by retirees bearing colorful signs. Its Belfast campus was freshly posted against trespassers and bristled with security officers. I asked one what the concern was.

“Liability,” he said. “We’re just trying to make sure everyone’s safe.”

How strange, I thought. That’s precisely what these protestors are saying motivates them. They fear for their children and grandchildren, for countless threatened wildlife species, and for marine life struggling in oceans that hit record-high temperatures in recent weeks.

“People are overwhelmed and frightened,” said Deborah Capwell, a grandmother at the Belfast action. “It’s easy when one is fearful of climate change to be immobilized and just give up.” But she’s convinced that retirees are perfectly situated to use their time and resources to push for climate action; “I hope more people will speak out.”

For members of Third Act, working collectively provides a powerful antidote to the isolation older people can feel. “We don’t count as much in this culture when we’re elderly,” Fuller said, yet “[we have] a lot of experience and wisdom, and we care a lot.” Third Act taps into that, re-energizing the political sensibilities of a generation that grew up on activism. “When we were in our 20s,” Fuller added, “we were protesting loudly and trying to save the world.”

Another strength that older people bring to activism often goes unrecognized, said Kathleen Sullivan, a retired therapist, writer and climate organizer in Freeport who helped establish Third Act Maine: “We don’t care what people think of us. There’s a freedom that comes at this stage to be able to dance in the streets about this, or speak out.”

That liberation was on display in Belfast, where protestors — swinging to the beat of a portable boombox — sang new lyrics to the 1957 Everly Brothers’ hit, “Wake up, Little Susie:”

“We’ve all been fast asleep, banking like we were sheep, we’ll cut our cards, we’ll pull our dough, the profiteers will weep, Wake up little Snoozie, wake up!”

Most Americans are “alarmed” or “concerned” about global warming but there’s still a taboo about discussing the topic, even among candid older people, Sullivan said. She hopes Third Act will inspire more dialogue, helping us face our complicity in climate upheaval.

Intergenerational Cooperation

In Maine and around the globe, young people have led many of the climate actions in recent years, and McKibben wants Third Act to support them. “It’s not fair to ask 18-year-olds to solve this problem,” he told the Guardian last month.

Similar to older people, youth can experience isolation when closed out of decisions driven by money: “The power adults hold that youth do not is financial power,” said Anna Siegel, a core member of Maine Youth for Climate Justice. It’s critical to have retirees engaged, she said, “because of the way wealth accumulates over a lifetime.” She hopes to see more older people helping to underwrite the climate work of youth, through event sponsorships, stipends and other means.

Third Actors and other retirees, for example, could support the intergenerational alliance advocating for the Pine Tree Amendment, LD 928, Siegel said, which would provide voters a chance to enshrine in Maine’s constitution the right to a healthy environment “for the benefit of all the people, including generations yet to come.”

Decisions made without an intergenerational perspective contributed to the climate crisis. Now there’s no avoiding the long view; as the IPCC report noted, “the choices and actions implemented in this decade will have impacts now and for thousands of years.”