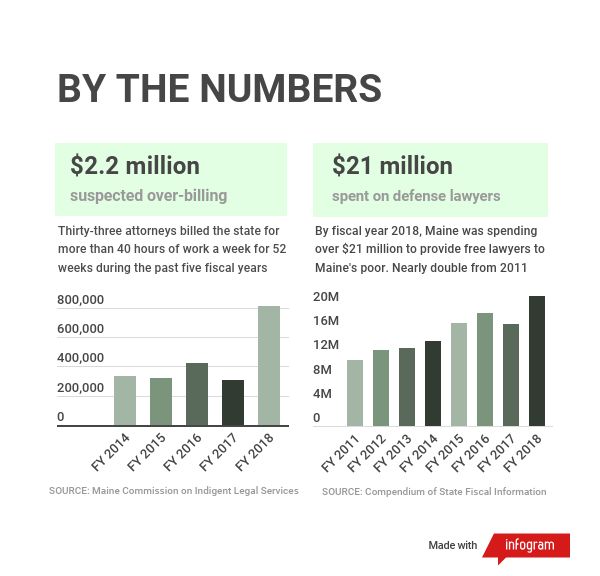

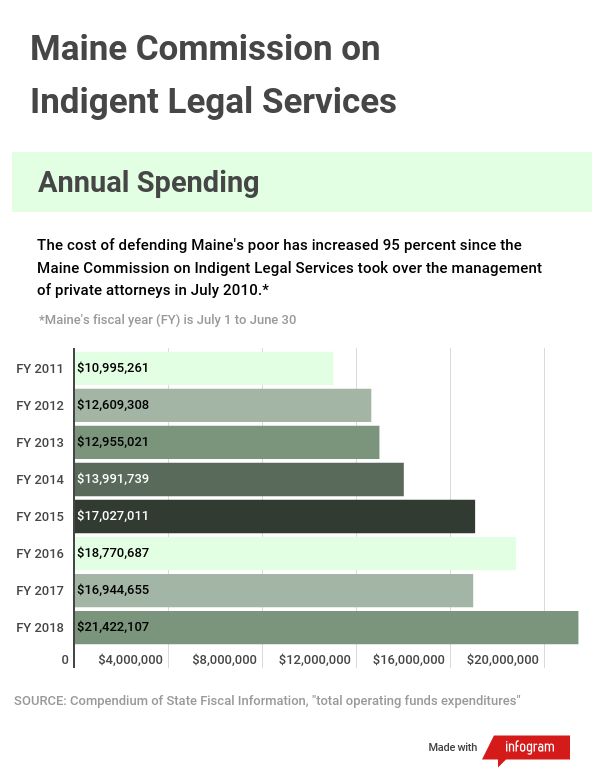

Maine spent more than $21 million to provide free lawyers to its poor in 2018, but the state’s oversight of the spending was so lax that they paid some attorneys as if they worked more than 80 hours a week for the entire year.

A three-month investigation by the Maine Monitor into the Maine Commission on Indigent Legal Services found that attorneys’ invoices are frequently incorrect, resulting in them often being overpaid for representing Maine’s poor. For nine years, the commission’s director has uncovered these inaccuracies on a daily basis, but he did not change how attorney payments are approved even as the agency’s spending nearly doubled.

Lawmakers began to question the commission’s financial oversight earlier this year after a report by the nonpartisan Sixth Amendment Center revealed that 33 attorneys could have over-charged the state $2.2 million between 2014 and 2018 by billing hours that greatly exceeded full-time work.

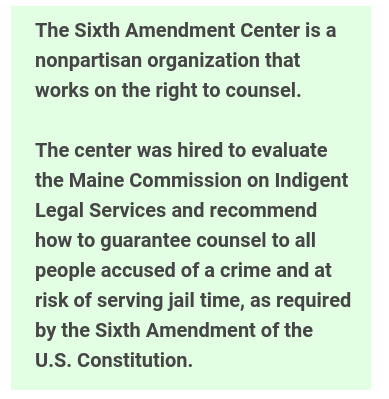

The highest paid attorney was Amy Fairfield, who personally billed the state $275,612 in fiscal year 2018. At the state’s flat $60-an-hour rate for court-appointed attorneys, that would mean she worked approximately 88 hours a week, excluding a small amount of expenses.

The commission’s executive director, John Pelletier, said what Fairfield was paid in fiscal year 2018 was not over-billing but the cumulative work of multiple attorneys at her law firm who worked on her cases and billed under her name.

The commission instituted an alert system in June to detect when lawyers invoiced the state for an excessive number of hours. In just four months, the system triggered more than 800 alerts when attorneys appeared to have over-billed, including several days in which a lawyer claimed to have worked more than 24 hours in a single day.

Maine is the only state that does not have a public defender office staffed by its own attorneys. Defendants who cannot afford to hire a lawyer instead rely on the Maine Commission on Indigent Legal Services, which oversees private attorneys who are assigned to represent the poor in criminal, juvenile and child protection cases.

The Sixth Amendment Center report set off a chain of inquiries by lawmakers with Sen. Lisa Keim (R-Oxford) at the forefront of the push to investigate.

Since 2016, Keim has filled a blue, three-ringed binder with a stack of research on the “opaque” billing practices of the commission. In February, she asked the Government Oversight committee to open an investigation into whether attorneys were falsifying their hours, and pointed to Fairfield’s earnings in 2018 as a concern.

The Government Oversight committee unanimously agreed to have the state’s independent Office of Program Evaluation and Government Accountability (OPEGA) begin a review in April. They are scheduled to meet again on December 10 to consider whether to launch a deeper investigation.

Banking on high hours

For nearly a decade, Pelletier and Ellie Maciag, the commission’s deputy director, have approved payments to defense attorneys based on the average time it took other lawyers to complete case tasks and what they called a “feel” for the expected time a case should take.

However, in July 2010, the commission’s first operational report pointed out that reviewing payments by case alone left the agency blind to the total hours attorneys billed each day. The report suggested a timesheet be added so attorneys could track their daily hours worked across multiple cases. The commission wanted the change made by that fall, but nine years later, it has not been implemented.

The blind spot in the commission’s understanding of attorney billing became apparent this summer when a new alert system to detect when lawyers billed 12 or more hours went live and flagged more than 800 days that attorneys could have over-billed.

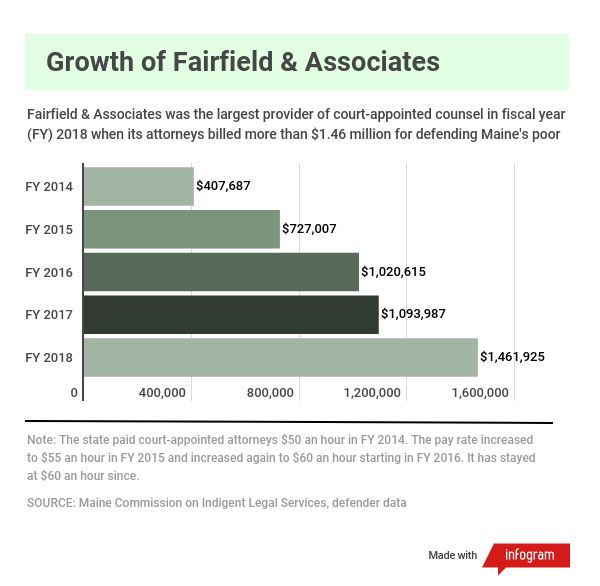

Twenty-seven percent of the alerts trace back to the Fairfield & Associates, which Amy Fairfield opened in 2004.

In fiscal year 2018, Fairfield & Associates billed $1.46 million as the state’s largest provider of court-appointed counsel. One of the highest-billing associates at the law firm, Kevin Moynihan, racked up more alerts than any other attorney in the state during the first four months of the new system coming online.

Invoices that Moynihan submitted in June triggered alerts on 93 days when his daily workload exceeded the system’s 12-hour limit. This included his highest billed day on Aug. 13, 2018, when he invoiced the state more than 21 hours on 40 cases.

When reached in October, Moynihan told the Maine Monitor that he worked the hours billed on the cases, but that some hours were invoiced on incorrect days by staff at Fairfield & Associates.

Moynihan left Fairfield & Associates for a job at the Cumberland County District Attorney’s office in late June as the commission’s alert system was being rolled out. He was able to check only a few of the alerts before he was locked out of the firm’s email and internal billing system where his hours were stored.

The alert system was implemented at the recommendation of Pelletier and Maciag, and was the first major change in nine years to how attorney hours were monitored by the agency. A proposal to add a timesheet is also pending with the independent board of commissioners that advises the state agency. Pelletier said a timesheet would be beneficial and could limit mistakes.

A the Maine Monitor review of attorneys’ explanations to the high hour alerts revealed multiple instances where lawyers found they had billed the state twice for the same work, forgotten decimal places or recorded tasks on the wrong day, which required their future bills to be adjusted for the overpayment.

When asked to explain the high volume of alerts, Pelletier said they were not indicative of intentional over-billing.

“We’re finding errors in the billing, and some reflect work that’s done and some is work that was not done — but it’s accidental,” Pelletier said.

Attorneys had not responded to 46 percent of the alerts by the first week of October, which meant the commission had no explanation for the high number of hours billed. Pelletier says he has monitored attorney responses and requested explanations when he felt the attorney did not provide enough information.

“We’re finding some people who worked very long days,” Pelletier said. “When they write and explain what the 16 hours was composed of, it’s credible to me.”

But Pelletier has dismissed multiple over-billing concerns Lynne Nash, the commission’s accountant technician, has raised in the nine years they have worked together. Nash says she brought law firms, attorneys and experts who she suspected of over-charging the commission to Pelletier’s attention.

Pelletier said he scrutinizes some of the invoices Nash flags, but that there are times when he finds the charges to be reasonable when Nash does not. That includes the findings of the Sixth Amendment Center report.

The Sixth Amendment Center was hired in March 2018 at the recommendation of a legislative group led by Keim to evaluate the commission and make recommendations on how it could better guarantee counsel to all people accused of a crime and at risk of serving jail time. The report uncovered multiple systemic problems with Maine’s ability to provide defense and the potential over-billing problem.

In July 2018, after releasing never before seen data on attorneys’ annual billings to the Sixth Amendment Center, Pelletier immediately opened an investigation into the billing practices of all attorneys who billed $150,000 or more a year from the commission. He met behind closed doors with three commissioners about his findings, records show, but his only public conclusion was that there was no evidence of fraud or a need for disciplinary action.

“I’ve determined that there won’t be any sanction or discipline among the lawyers that I looked at, because I didn’t find conduct that was worthy of that,” Pelletier told the Maine Monitor.

According to Nash, the decision not to sanction any of the attorneys was an accountability failure by the commission.

“I’ve lost a lot of respect for John Pelletier,” Nash said. “I would like to see someone put in place that is held accountable for the expenditures going through that agency, because right now it’s just not happening.”

Maine’s highest billing firm

The only person making more money at Fairfield & Associates by representing Maine’s poor defendants when Moynihan left was its founder and CEO, Amy Fairfield.

Pelletier told lawmakers that the $275,612 Fairfield billed in fiscal year 2018 was proper because it reflected the work of multiple lawyers at Fairfield & Associates and not Fairfield alone.

However, Pelletier did not mention in his letter to lawmakers that four attorneys at Fairfield & Associates, who shared at least some of Amy Fairfield’s cases, were also among the highest billers in the state that year and were pegged for potentially over-billing in the Sixth Amendment Center report. Fairfield & Associates was the only law firm to have multiple attorneys flagged for potentially over-billing the state every fiscal year between 2014 and 2018.

Time — billed in one-tenth of an hour increments — constitutes the majority of an attorney’s invoice to the commission. Certain costs for collect calls, travel and copying of more than 100 pages can also be reimbursed, but they make up substantially less of an attorney’s billings from the commission.

In addition to Fairfield and Moynihan, Fairfield & Associates attorneys Sarah Branch ($132,000), Cory McKenna ($137,000) and Rick Winling ($143,000) each billed the state above what would be expected had they worked 40 hours a week all 52 weeks in fiscal year 2018.

Fairfield declined multiple requests for comment on her law firm’s billing practices.

McKenna left Fairfield & Associates on September 12 and joined McKenna Deschuytner, PLLC in Portland. McKenna said he earned approximately $67,000 last year, which is substantially less than the $137,363 that commission records show he billed the state for defending Maine’s poor.

“Even if I earned $137,000, that would probably be what it would cost to support a law practice dedicated to criminal defense, when you factor in all the expenses from office space, equipment, services, staff, health care, retirement, etc.,” McKenna wrote in an email on November 12.

“It is my understanding that Maine is unique in the nation in that it does not have any public defender system. It provides extremely high quality defense to the poor solely through private attorneys who agree to work on matters for a third to a fourth of their normal rates,” he added.

To understand how the lawyers at Fairfield & Associates could have profited from the defense of Maine’s poor, the Maine Monitor analyzed invoices and case files of former clients of Fairfield & Associates, three years of commission payments, and five years of financial data that underpinned the Sixth Amendment Center report.

However, there is no public information currently available that describes in detail the number of hours each of the attorneys at Fairfield & Associates actually worked during the 2018 fiscal year.

Pelletier denied a public records request by the Maine Monitor for a report of attorneys’ daily hours, saying it was a confidential piece of his 2018 investigation into attorney billing practices.

The annual earnings of each attorney can only be used as an approximation of how much time they worked during the fiscal year, because attorneys at Fairfield & Associates completed work on cases assigned to other attorneys at the law firm and didn’t always bill under their own names.

In some instances, the court-assigned attorney at Fairfield & Associates would do little to no work at all on a case that carried their name, Pelletier said.

“We knew on a regular basis that there were cases where the name of the assigned counsel was not the person doing most of the work on the case,” Pelletier said.

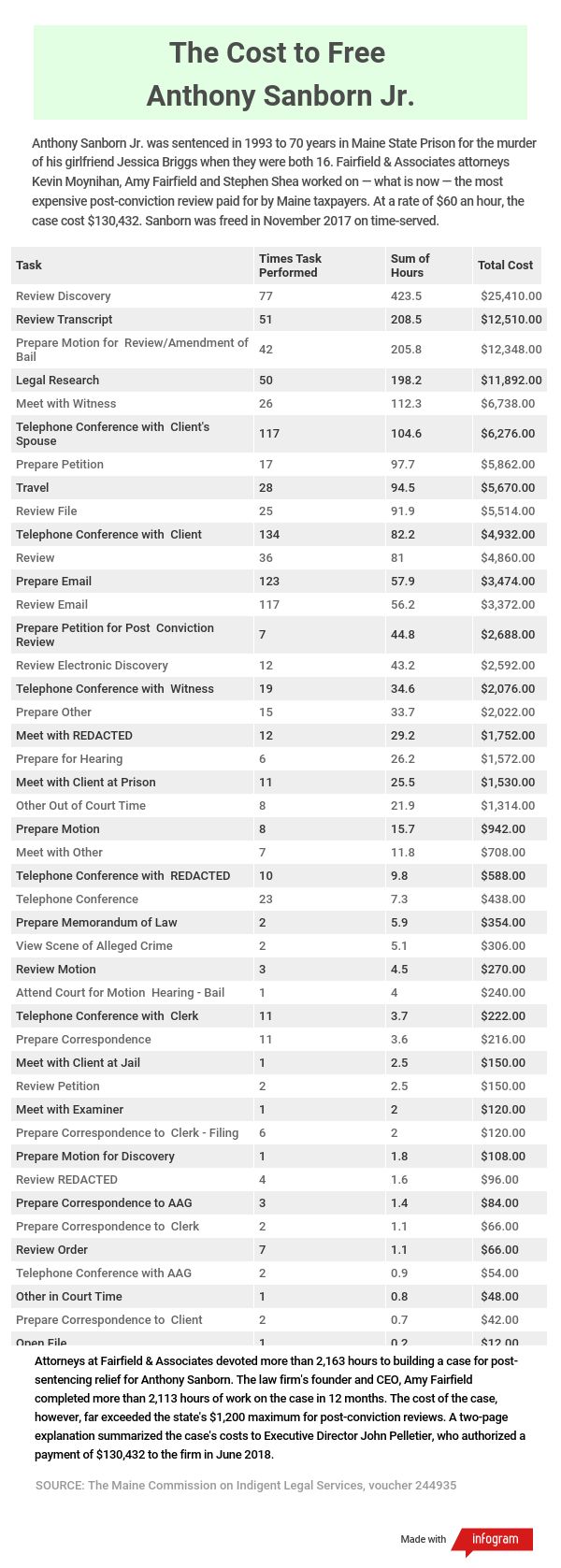

The most notable example came while Amy Fairfield worked on a post-conviction review for Anthony Sanborn Jr., who was sentenced in 1993 to 70 years in Maine State Prison for the murder of his girlfriend Jessica Briggs when they were both 16.

According to Pelletier, nearly every case that Fairfield was assigned by the courts — while she was working on the Sanborn case — was completed by other attorneys at her office.

The Maine Monitor obtained through a public records request the invoice that Fairfield & Associates submitted for the Sanborn case, which showed that Amy Fairfield spent more than 2,113 hours between May 2016 and April 2017 working on the case. It was the first post-conviction review that Fairfield had ever completed.

“The material was dense and a lot of it did not make sense. I quickly learned that it was not supposed to (make sense) because it was a bullshit prosecution that yielded a verdict that no one in their right mind could have confidence in,” Fairfield wrote to Pelletier in her explanation of the case’s costs.

Fairfield spent 423 hours reviewing discovery and another 208 hours reviewing the transcript of Sanborn’s original trial, which was more than 1,800 pages long.

A deal with prosecutors in November 2017 freed Sanborn on time-served while maintaining his murder conviction, The Portland Press Herald reported.

The maximum fee a court-appointed attorney can charge for a post-conviction review is $1,200, according to the commission’s rules. In June 2018, Maine taxpayers paid Fairfield $130,432 for Sanborn’s case. It is the most expensive single invoice and post-conviction review ever paid out by the commission.

“Working with Tony Sanborn enriched my life in many ways,” Fairfield wrote. “Working on his case illuminated a lot of ugly truths. The hours contained herein are probably far less than I actually worked. Many nights I would get a couple of hours of sleep and then get right up and start reading and analyzing right where I left off. It was an insatiable desire to achieve justice for a wonderful human being that had been tossed away as a street kid who nobody really cared about anyway.

“Words cannot describe the time and effort that went into this case. Please know that I will happily accept whatever MCILS deems appropriate for compensation. I know the bill is sizable; we did, however, take on an empire.”

Fairfield’s work on the Sanborn case, however, accounts for less than half of the $275,612 she billed in fiscal year 2018 and leaves an estimated 46 hours a week unaccounted for in the remaining $145,180 billed under her name that year.

Co-Chairs of the Government Oversight committee Sen. Justin Chenette (D-York) and Rep. Anne-Marie Mastraccio (D-Sanford) declined to comment on the ongoing investigation into the commission and its payments to attorneys beyond saying that the vote to initiate a review in April, itself, was a comment on the situation, Mastraccio said.

The scope of the OPEGA investigation has not yet been defined. But Keim said determining the culpability of attorneys and staff involved in the alleged over-billing will eventually be necessary.

“If you lead an organization you always have to be willing to say the buck stops here. If you’re willing to say I’m the executive director of this organization, you have to be willing to say whatever goes wrong in that organization is on my shoulders. And I know that the people of Maine pay (Pelletier) to take it on his shoulders,” Keim said.

Concerning cash flow

Each morning, an email arrives in Lynne Nash’s inbox with the total amount of money her bosses approved the day before. It’s been her job as the commission’s accountant technician since June 2010 to make sure the information on how much attorneys are paid flows into the state’s accounting system.

Any time the daily payment exceeds $60,000, Nash said she begins to question the accuracy of what has been approved and sometimes opens a detailed list of the invoices. That’s how she became wary of what Fairfield & Associates was billing.

“There’s a high-billing firm that needs a full-blown audit, and I’ve requested this of management numerous times for many years now,” said Nash, referring to Fairfield & Associates.

However, her requests for an audit never went anywhere, even after she brought her concerns to Chair Steven Carey of the agency’s independent board of commissioners. Carey did not respond to multiple calls requesting comment from the Maine Monitor.

On October 30, 2018, Nash went above Pelletier and emailed the state commissioner of finance, controller and later the state auditor requesting they look into how attorneys were billing the commission.

“Any concerns regarding improper billing practices for Indigent Legal Services, or in any other area, would have been taken seriously, reviewed with the appropriate Department professionals, and addressed accordingly,” former Commissioner of Finance Alec Porteous said in an email in October.

As it turned out, potential vulnerabilities in the commission’s invoicing system, Defender Data, were already being reviewed by the Office of the State Controller when Nash’s email arrived, said State Controller Doug Cotnoir, who has overseen the financial management of the state since 2012.

His office released a report on March 14 that found the commission lacked written control procedures and had multiple other system vulnerabilities that the Controller’s office identified as risks. The details of the report were heavily redacted for security purposes before it was publicly released.

In an unredacted section of the report, the Controller’s office concluded that the commission was properly processing payments. An audit team reviewed a random sample of 40 invoices and found the commission was paying the correct vendor in amounts that matched the hours billed.

The report did not look into the accuracy of the individual charges on the invoices. It is Pelletier’s responsibility — not the controller’s — to confirm that the work paid for was rendered, Cotnoir said.

“We don’t do performance reviews on our side, and that is where we cross into where OPEGA comes into the picture,” Cotnoir said. “We try not to step on each other’s toes. I don’t want to compromise any work that they’re going to be doing and they try not to compromise any work that we may have underway.”

Whether attorneys are billing for work they actually performed is a question of performance, which would be appropriate for OPEGA to look into, he said.

The controller’s office provided its complete findings to OPEGA, and handed off control of any further review to the independent agency, Cotnoir said.

Members of OPEGA’s staff visited the commission and met with Pelletier, Maciag and Nash in early November, Pelletier said. OPEGA has also interviewed several of the commission’s employees and Pelletier twice, he said.

The volume of invoices Pelletier and Maciag can review in a day varies widely depending if the Legislature is in session — when Pelletier is frequently away from the office at the Capitol — and how close it is to the end of the financial quarter, when there is a push to make payments. Both overlap each March.

March 27, 2017 sticks out in particular. Records show 606 attorney invoices were reviewed and approved for payment that Monday, sometime between Friday and Sunday at the end of a busy legislative week, which included multiple committee meetings that Pelletier was known to attend.

Maciag estimated that she and Pelletier spend on average between one and two minutes with an invoice before it’s approved.

But spending just two minutes with each of the 606 invoices would have taken more than 20 hours.

Pelletier said the 606 invoices — worth $368,098 — were approved over a three-day period. Pelletier and Maciag both reviewed vouchers on Friday, and Pelletier worked Saturday and Sunday to review and approve the rest.

This would have been a break from normal behavior as Pelletier acknowledged he rarely worked weekends. Maciag also was about to take time off for maternity leave.

“You have to wonder how accurate the review process was to accumulate that amount of money in one day. Even with two people,” Nash said.

In all, Pelletier and Maciag reviewed and approved 3,266 attorney invoices, worth more than $1.9 million, in March 2017.

Multiple lawmakers, defense attorneys and advocates interviewed by the Maine Monitor also raised concern with Pelletier dividing his work day between completing tasks for the commission and a volunteer role as chair of the state’s Criminal Law Advisory Commission (CLAC).

Since 1997, Pelletier has served as chairman of CLAC, which makes annual recommendations to state lawmakers on possible changes to Maine’s criminal code. Pelletier regularly attends legislative meetings and speaks on behalf of CLAC.

In January 2010, Pelletier was hired as executive director of the Maine Commission on Indigent Legal Services, which has not taken positions on policy matters before the state legislature in the past.

CLAC meets approximately every other week while the legislature is in session, Pelletier said. When he is at the state capitol during session, it is generally on behalf of CLAC, he said.

Pelletier would tell the office staff, “Thursday was a CLAC day,” Nash recalled, “So we knew Thursday, Friday were pretty much dead in the water.

“Any time there is anything in the legislature’s schedule to do with CLAC, any type of bill, he’s up over the hill … there speaking on the behalf of CLAC. Sometimes it can be daily. It can be anywhere from an hour to an all day,” Nash said.

Pelletier’s job with the commission was salaried at $121,800, including benefits, in fiscal year 2018. Pelletier said he did not take vacation or sick time to speak on behalf of CLAC.

“My work at the commission gets done,” Pelletier said.

Catching bad billing

On at least two known occasions, Pelletier and Maciag’s review process has failed to immediately catch over-billing.

The most recent example was uncovered during Pelletier’s investigation of attorney billing practices in the summer of 2018. A lawyer, whose identity is confidential by law, was caught double-billing the commission for his and a staff member’s time.

Pelletier said he would not have been able to identify the over-billing through his regular review process, and it required looking at the attorney’s annual earnings to uncover the pattern of over-billing.

The lawyer is expected to make a “substantial” reimbursement to the commission for the incorrect invoices, Pelletier said. The amount of the reimbursement has not been finalized and has not yet occurred.

The other instance of over-billing spanned the first four years of the commission’s operation.

Aaron Fethke, an attorney with a practice in Searsport, aggregated the hours he worked on multiple days and billed them as one, which resulted in more than 24 hours being billed on a single day, according to disciplinary documents with the Board of Overseers of the Bar.

Because the automated alert system was not in place at the time, Pelletier was not immediately aware that this was happening. Instead, it was the unusually high number of hours that Fethke was billing to review discovery and other tasks that tipped off Pelletier that Fethke’s invoices may have been inflated.

Fethke billed $194,488 representing Maine’s poor in fiscal year 2014, which was more than any other attorney. The following fiscal year, he billed $160,086 and was the second highest paid attorney behind only Amy Fairfield.

On July 10, 2015, Pelletier filed a complaint with the Board of Overseers of the Bar on the grounds that Fethke was misrepresenting the time he spent on cases and over-billing the commission for his work. He suspended Fethke from the state’s list of eligible attorneys for court appointments.

In January 2017, the Maine Supreme Judicial Court ordered that Fethke be suspended from practicing law for four months for his violation of the Maine Rules of Professional Conduct and the Maine Bar Rules. But while the court found Fethke’s billing practices to be “unorthodox and inappropriate,” they did not determine that he had intentionally over-billed the commission. Fethke did not repay the commission.

“Looking back on it, we probably could have heightened the scrutiny at an earlier time, but we did when we did,” Pelletier said.

But even after Fethke’s discipline case showed the commission’s system Defender Data could be exploited to over-bill the state, Pelletier and Maciag did not change their invoice review process.

“Why in 2014 when they knew that Defender Data allowed an attorney to bill over 24 hours in a day, why at that time did they not think outside the box and say we need — as we now have in place — this alert system? How many millions of dollars do you suppose the taxpayers have lost?” Nash said.

The proposed rule to add a timesheet to track attorney hours is waiting for approval by the commission’s new board of commissioners, Pelletier said. Lawmakers restructured the commission in 2018 and replaced the three existing commissioners with a nine-member board.

The new commissioners were confirmed by the state Senate this year and began meeting in August. They will host a public hearing on the findings of the Sixth Amendment Center report at 9 a.m. on November 19 at the capitol.

Keim said she cannot read the Sixth Amendment Center report without concluding there had to be a breakdown in oversight within the commission.

The data on attorney earnings were at the executive director’s fingertips, but he hadn’t looked at it until the researchers requested it, Keim said.

“I think we need to clean house,” Keim said. “The only way you rebuild the system and have faith in it is if you make sure you get rid of people that didn’t have the integrity in the first place.”