During the past five months of the coronavirus pandemic, Mainers and other Americans have been inundated with numbers. Confirmed COVID-19 cases per capita. Death rates. Test positivity rates. Hospitalization rates. Available ICU beds.

There is a staggering number of ways to measure the pandemic. So what are the most important metrics now and moving forward?

The Maine Monitor spoke with four public health experts about the figures they use to best understand COVID-19 — and the limitations of what those numbers convey.

All four agreed that the percentage of positive COVID-19 tests and the number of new cases are important indications of the state’s testing and handling of the virus, although there was some disagreement on how this data should be presented. Other important metrics they cited included the state’s volume of testing, hospitalization rates and the level of adherence to safety precautions.

Matthew Fox, a professor of epidemiology at Boston University, said Maine has “done a very good job” handling the pandemic. He bases his evaluation on the positivity rate, number of new cases and hospitalization rates.

Dr. Nirav Shah, director of the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention, said he and his team check the same three metrics every morning: the seven-day positivity rate, the number of new cases and the volume of tests per 100,000 people.

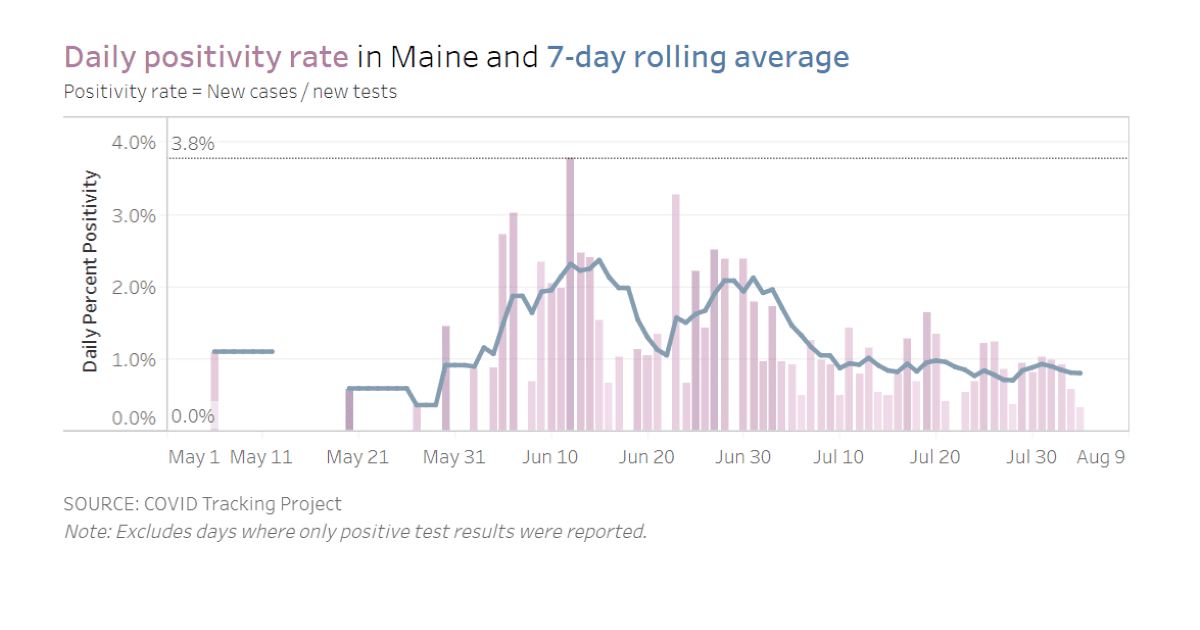

Based on those figures, Maine is doing well compared to the rest of the country. On Aug. 4, Shah reported the seven-day test positivity rate had dropped to a new low of 0.87 percent and last month Maine was one of the few states to see a decline in new cases. The state started ramping up testing last month and reported 171 tests per 100,000 people on Aug. 6. And 9 people were hospitalized in Maine.

But still there is a cost: 125 Mainers and more than 160,000 Americans have died from COVID-19. And the threat of a surge hasn’t disappeared.

“Just because the numbers are low now doesn’t mean they’re going to stay that way,” Fox said. “The more we open up, the more things are going to come back. And what we need are plans for how we’re going to prevent that from becoming a big spike again.”

Positivity rate

The positivity rate, also known as the positive test rate, is the percentage of results that come back positive for COVID-19 out of every test conducted. It reflects how much a state is testing and therefore whether its number of confirmed cases is reliable, Fox said.

If the positivity rate is low, that means the state is testing broadly and the number of recorded COVID-19 cases is fairly accurate.

“If that positivity rate starts to go up, sure, it’s likely to be an indicator that things are getting worse. But what it really should tell you is that you need to ramp up testing,” Fox said.

Shah reported Maine’s seven-day test positivity rate as 0.9 percent at his most recent briefing on Aug. 6. This means less than one out of every 100 tests comes back positive for COVID-19. Other national tracking outlets, including the COVID Tracking Project, COVID Act Now and Johns Hopkins Univerisity’s Coronavirus Resource Center, record positivity rates differently and found an even lower seven-day positivity rate in Maine on Aug. 6, at 0.8 percent. Those outlets reported Maine’s positivity rate at 0.6 percent on Aug. 8.

The seven-day “moving average” of the positivity rate, instead of the rate from a single day, because it gives a clearer picture of how the outbreak is changing and whether testing strategies are sufficient, Shah said.

When the positive test rate gets higher than 5 percent, Fox noted, “then you can be pretty sure that you’re not doing enough testing to really have a good sense for exactly where things are going and where the outbreaks are happening.”

As of Aug. 8, 35 states have positivity rates above 5 percent, including Mississippi (20.5 percent), Florida (17.7 percent) and California (5.7 percent), according to COVID Act Now.

Positivity rates also can indicate when states should reopen parts of their economy. To reopen responsibly, the positive test rate needs to be below 3 percent, according to Dr. Vin Gupta, professor of Health Metrics Sciences at the University of Washington. At that point, states can move from mitigation efforts such as sheltering in place to containment and contact tracing, he said recently.

Prior to the coronavirus pandemic, Gupta worked with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, the Harvard Global Health Institute, the World Health Organization and the Pentagon’s Center for Global Health Engagement. He recently served as the primary public health consultant on pandemic emergency financing for the World Bank.

Contact tracing becomes “utterly useless” in states with high positivity rates, Gupta said, “because at that point we think the outbreak is out of control. You’d be contact tracing everybody. And we think you need five tracers for every confirmed case to do it well. How can you do it if an outbreak is out of control?”

Contact tracing is a method of monitoring and containing the virus by calling everyone who has tested positive and asking them who they’ve been around. Tracers then call those contacts and ask them to quarantine for two weeks.

Fox agreed that states with high positivity rates “are never going to solve the problem through contact tracing.” But he said tracing still is useful as part of a strategy that includes masks, social distancing and other methods to reduce the spread.

“I think you have to remember that every infection that you prevent doesn’t just prevent that single infection. It prevents all the infections to anyone they transmit to,” he said.

Number of new cases

The number of new cases relies on context to convey meaning — it is only representative if states are testing enough.

As COVID-19 cases continue to climb in the U.S. — now nearing 5 million — Maine was one of the few states to report a decline in new cases in July, although they started to creep up again at the end of the month.

Because the state’s positivity rate is low, and therefore the number of recorded cases is relatively trustworthy, Fox said “the falling numbers in Maine is absolutely a good sign.”

Part of Maine’s success could be tied to its low population density, he added.

During a press briefing last month, Gov. Janet Mills called the decline in cases “encouraging news.”

“But I want to be clear, it’s not cause for celebration,” she continued. “We’re not going to sit on our laurels. As much as we’d like to think things are over, we know they’re not over.”

Dr. William Salomon, a public health informatics consultant and former medical director of the neonatal ICU at Central Maine Healthcare in Lewiston, agreed that declining cases is a positive sign.

But he also said it’s important to track new cases on a per capita basis — instead of the flat number of new cases released daily by the CDC — because the rate paints a clearer picture of outbreaks and should guide the public health response in individual communities.

Salomon said he has not formally consulted for the Maine CDC during the pandemic but started digging into the available data because he felt it wasn’t presented in a way that was useful for public health intervention.

The number of new cases per capita allows county-by-county and state-by-state comparisons to see who is faring better or worse, he said, especially when officials start talking about reopening parts of the economy. The public health approach should be different in communities with a high per capita rate of cases compared to those with a low rate, where a greater emphasis should be placed on education to prevent a future outbreak, Salomon said.

For instance, Cumberland County has by far the most COVID-19 cases: 2,082 as of Aug. 7. Next door, Androscoggin County has much fewer cases at 558, but when these numbers are adjusted for population, the rates are more similar. Cumberland has 71 cases per 10,000 people and Androscoggin has 52 cases per 10,000 people. Kennebec County, meanwhile, has 170 cases but a per capita rate of about 14 cases per 10,000.

Volume of tests

The number of COVID-19 tests per capita is another way of evaluating the state’s overall testing capacity.

Despite recent declines in cases, Maine has continued to ramp up testing.

The Maine CDC has tested 171 out of every 100,000 Mainers as of Aug. 6. This is an increase of about 70 percent from mid-June, according to Shah.

Fox and Salomon said Maine is doing a pretty good job of testing, but to tamp down the pandemic, testing should be available to everyone.

Last month, the state announced it would partner with seven health care organizations to launch 18 “swab and send” test sites across the state. These sites will be available for people who have COVID-19 symptoms, have come into close contact with those who have COVID-19 or have an elevated risk of being exposed to the virus.

But for those who are just curious about whether they have the virus, “that’s not a good use of a test,” said Jeanne Lambrew, commissioner of the Department of Health and Human Services.

Fox, the Boston epidemiologist, said he understood the need to conserve limited resources. But he’d like to see testing eventually used proactively instead of reactively.

“I’m not critical of that decision (to restrict testing), given where we are. I’m saying we shouldn’t be in that position,” he said.

Salomon, the public health informatician, said the problem with limited testing is it’s “self-selecting,” meaning only people who already are feeling sick go in for a test. To better understand the pandemic, he said, the U.S. needs to do randomized samples of the population, which Europe and South Korea have done.

Maine and the U.S. haven’t been able to ramp up this kind of widespread testing because public health recently has been underfunded and undervalued, he said.

Hospitalization rates and other numbers

While tests per confirmed case and positivity rates are good initial measurements of an outbreak, Gupta said hospitalization rates, ICU bed availability and death rates can be a “late-stage indicator” of the pandemic’s impact.

These metrics, however, are more nuanced. For instance, hospitals often only have enough staff to manage about 75 percent of the available ICU beds, Gupta said.

Maine has not come close to overwhelming hospital bed capacity throughout the state.

Between late April and early July, deaths nationwide trended downward, but much of that was tied to a rise in younger people getting infected and doctors learning how to better treat the virus, Gupta said.

In Maine, most cases have been found in people younger than 50, but nearly all of the deaths have been people 60 and older, according to CDC data.

“We know things that we didn’t know in March,” Gupta said. “It doesn’t mean then that we should be playing Russian Roulette with ICU bed capacity.”

In early July, deaths nationwide started to climb again, according to the COVID Tracking Project, an effort from The Atlantic to collect and publish data related to the U.S. outbreak.

Fox said even the smallest percentage increase in young people dying from COVID-19 is “very troubling” because the probability of them dying is very low.

“Small percentages in increase in deaths in those age groups is quite large relative to what we’d expect,” he said. “We don’t want to lose anybody, but we certainly don’t want to lose people who are young and healthy.”

Asked if Maine is doing enough to address the pandemic, Salomon said, “I think it’s a fair effort.” But he added the state could do a better job crafting a message that’s appropriate for each municipality.

Part of that effort depends on knowing how many people are following health recommendations, he said. One way to study that is to send volunteers to five places around town, such as grocery stores, to count how many people are wearing masks. This measure of “adherence” could then be mapped alongside the location of outbreaks.

And research facilities, if they haven’t already, should start recording and tracking the long-term effects in people who had COVID-19, Salomon said.

Despite Maine’s decreasing case numbers, Gov. Mills urged people to stay vigilant.

“We’ve got to remind ourselves every day that this deadly virus is still here,” she said. “It’s lurking in our communities across the state. When it takes hold, things can turn around in a jiffy, in a heartbeat. … Maine people have done an extraordinary job steadying the tide of this virus but we can’t let up right now.”

Maine Monitor contributor Darren Fishell created the data visualizations for this story.