There were so many questions.

Why don’t I feel comfortable in my body?

Why do I feel so alone?

And perhaps the most heartbreaking: Will I ever be loved?

As a child growing up in Maine, Aiden Campbell knew something wasn’t right.

Everything about his body felt mismatched and uncomfortable. Assigned female at birth, he gravitated toward boys’ clothing and male role models. At age 5, he didn’t understand why he was placed with girls when his school separated the class by gender.

In central Maine, where Aiden lived, there weren’t many openly gay students in Augusta or the surrounding rural towns.

“I was a freshman in high school before I even met anyone who identified as a lesbian,” Aiden recalled recently. “So that was like a whole new world for me; that kind of felt more right than just being like a straight cisgender woman.”

When he came out as a lesbian in 2010 at Cony High in Augusta, he found little acceptance. Aiden got pushed into lockers. Students called him names. During practice for field hockey or lacrosse, his backpack would sometimes disappear and get tossed in trash cans around campus.

At lunch he ate with a guidance counselor or teacher in their office or classroom to separate himself from other students. He seldom talked about his feelings or the harassment.

“I was embarrassed by it and didn’t really know how to talk about it,” Aiden said. “I think I was afraid for a long time that if I said too much, it would get worse.”

His mother worked with the school to get Aiden counseling, but by his junior year, Aiden had become deeply depressed and isolated. He felt betrayed and distraught over his maturing female body.

“I didn’t fit in,” he said, “and there was nobody like me at school.”

On a February afternoon, he walked to a dam near his home. He thought about the hate he felt from other students. Believing he would never be loved or accepted, he jumped off the ledge into the icy waters.

“But as soon as I jumped,” Aiden said, “it was just a bad feeling of instant regret.”

Unhurt in shallow waters, Aiden made his way to shore. A few days passed before he told the school’s career counselor about his suicide attempt.

“I was really afraid to tell her because I wasn’t sure what would happen … I was just trying to find help and I didn’t know how to ask for it.”

Aiden’s mother, longtime school board member Sue Campbell, received a phone call from the assistant principal on that winter day. She told Campbell that Mary, as Aiden was called at the time, had tried to kill herself.

“At that moment,” Campbell remembered, “my life stopped.”

Campbell had two children, her daughter and an older son. She knew Mary was taking medication to ease her depression, but Campbell was stunned that she hadn’t realized the depth of the suffering.

“Why didn’t you come to me?” Campbell asked.

“I was afraid I’d disappoint you,” her daughter explained.

Mary also had other feelings to share.

“I don’t even know if I want to tell you,” she said. “I think I should have always been a boy.”

At the time, Mary had never heard the word transgender or knew that she could receive treatment. Campbell reassured her daughter that she would support her transition, and began searching for resources and medical professionals. Like most Maine schools in 2012, Cony High had little to offer transgender students.

“I spent that whole summer reading every book I could possibly get my hands on,” Campbell recalled. “And then I shared everything with the school social worker, who was reading the books as fast as I was.”

Unable to find a Maine doctor who specialized in gender-affirming treatment, Campbell called medical providers in Boston and Providence, R.I., the closest places that offered care for transgender youth.

“When I started taking hormones, we had to go all the way to Rhode Island because (it had) the only doctor that would provide them for me,” Aiden said.

While Aiden wanted to “go a million miles an hour” to affirm his gender, his mother tried to process the transition.

“Oh my god,” she thought. “What does this mean?”

The daughter who loved to play the guitar, draw and write in her journal, the child Campbell thought would one day birth her own babies, would soon be a son.

“You have hopes and dreams of what your child will be like, and when that gets tossed on its head it can cause all kinds of emotions,” Campbell said.

But the moments of uncertainty dissipated when Campbell saw the changes. The day Mary had her first testosterone shot, Campbell and her daughter stopped for lunch in Rhode Island. Campbell watched as Mary got up to go to the restroom.

“She walked differently across that restaurant,” Campbell said. “She was more sure of herself.”

As Mary’s physical appearance changed with the testosterone doses, her self-esteem blossomed.

“I began to see that yes, this thing is right for us to be doing,” Campbell said. “I had a child who was depressed and suicidal change into a child who was confident, happy and able to thrive.”

The summer before her senior year, Mary chose to be called Aiden, a name he later learned meant “little fire,” which suited his personality. Though Aiden was quiet and reserved, when he was passionate about something, his mother explained, there was no holding him back.

While her daughter transitioned and went through male puberty, Campbell agonized about her child’s future. If students bullied Aiden as a lesbian, how would they treat him when he was the only transgender student in the school? How would Aiden handle the harassment and discrimination that many trans people faced?

And most of all, Campbell worried, “Is anybody going to love my kid?”

Aiden also feared his classmates’ reaction. He returned to school with short hair, a deeper voice and a more muscular body. To his surprise, no one taunted him, and some of the kids who had bullied him apologized.

“I don’t know if it was like a really intense thing, and they just really had no idea of what I was going through and felt bad, but it was completely different than what I was expecting.”

After graduating in 2014, Aiden attended the University of Southern Maine to pursue a degree in social work, so he could help other young people who struggled with adversity. While at college, he would continue administering his own weekly testosterone shots that induced his masculine traits and suppressed his feminine ones.

CLICK HERE TO SHARE YOUR THOUGHTS ON THIS STORY

Though he had a fresh start, Aiden worried about roommates and future girlfriends. How and when would he share his story?

Rather than room with a stranger who may be uncomfortable with a trans roommate, Aiden opted for a single residence. A couple weeks into his freshman year, his parents visited to celebrate his birthday. After they left, he brought his leftover cake to the lobby to share.

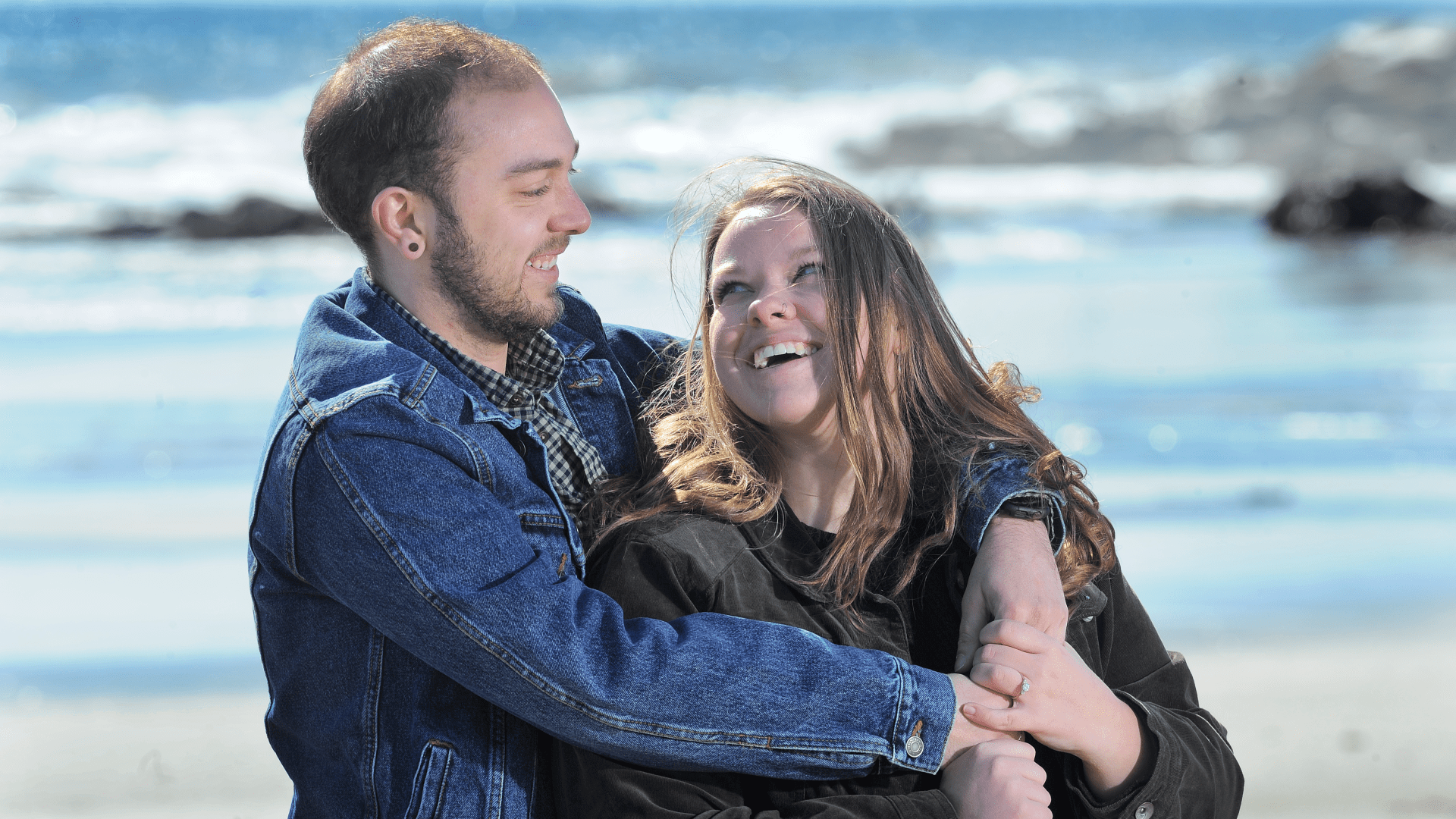

One of the students who accepted the cake was a blonde-haired girl from California named Casey Ross. Aiden liked her adventurous spirit and the way she made everyone around her feel comfortable. Unsure of how to tell her he was trans, Aiden called his mom.

“I met this girl and I really like her,” Aiden explained. “What do I do?”

“You need to talk to her,” his mother said. “You can’t start going out with her without being honest.”

Aiden worked up the courage to tell Casey he was transgender.

“I know, dummy,” Casey said and kissed him. She had learned about Aiden’s identity on Facebook and Instagram accounts where he was open about his gender.

By their sophomore year, Aiden knew he wanted to spend the rest of his life with the girl who made him happier than he had ever dreamed possible. Casey loved the young man who was kind and shared her passion for nature and outdoor adventures.

But she wasn’t ready to get married.

“Let’s just wait until I’m 24 and then we’ll see where we’re at,” Casey told him.

Years later, after he got his undergraduate degree, master’s in social work and served as a fraternity president — a first for a transgender male in Maine and the second to do so in the nation — Aiden and Casey are still together.

They bought a small gambrel in southern Maine in 2019, and adopted two dogs and a cat. The couple both found jobs where they could bolster the lives of young people. Aiden began working for OUT Maine, helping schools get resources and training for LBGTQ students. Because of his struggle to find help in high school, Aiden’s mother also started working at the Rockland-based organization, overseeing OUT Maine’s programs and educational outreach.

Casey, who earned a degree in recreation and leisure studies, landed a job with the Portland-based nonprofit Rippleffect, where she manages outdoor educational adventures for summer camps and after-school programs.

On a warm July afternoon in 2020 — Casey’s 24th birthday — she returned home to a note on the door that instructed her: “Come to the backyard.”

Casey opened the gate to find tiny lights with pink flowers strung along the wooden fence. A couple dozen photos hung from the light string showing Aiden and Casey smiling on mountain summits, kayaking in Maine lakes and posing in front of lighthouses. A bucket of champagne and a vase filled with flowers rested on a blanket. Aiden stood waiting with a grin and a small green box.

He got down on one knee and asked the words he had waited six years to say: “Will you marry me?”

Casey nodded as tears rolled down her cheeks. “Yes,” she told him.

This fall, the couple will marry on a Portland rooftop bar and celebrate with guests in the establishment’s lower-level bowling alley.

“Aiden’s not the biggest dancer,” Casey said. “So along with a band and dancing, we’re gonna have 12 lanes of bowling at our reception.”

Jordan Carpenter, one of the couple’s close friends, will serve as the maid of honor. Aiden and Casey’s relationship, she said, is inspiring.

“They are so incredibly perfect for each other and so in love,” said Carpenter.

Their wedding, she added, will be a “magical, beautiful celebration, and I cannot wait to be a part of it.”

Casey is counting the days until she can wear her champagne and ivory-colored wedding dress, and marry the man who makes her laugh and brings her joy each day.

After spending eight years together, Casey cannot imagine a future without Aiden. Her voice cracked and she wiped away tears as she talked about Aiden’s suicide attempt.

“I am so thankful that his mom was willing to save her child with whatever means it took,” she said. “And that Aiden was given the help he needed to grow into the person that he was supposed to be.”

The memories of that frigid February day are still vivid in Aiden’s mind. He knows how hopeless a young person can feel when believing they will never be loved or given the chance to transform into their true self.

It is for those kids that Aiden tells his story; it is why he works at OUT Maine as a mental health coordinator, helping schools set up Gay Straight Alliances and curriculum materials that are inclusive.

“When I transitioned, there were no role models, no resources and no one talked about being transgender,” he said. “I want people to know there is support out there for them.”

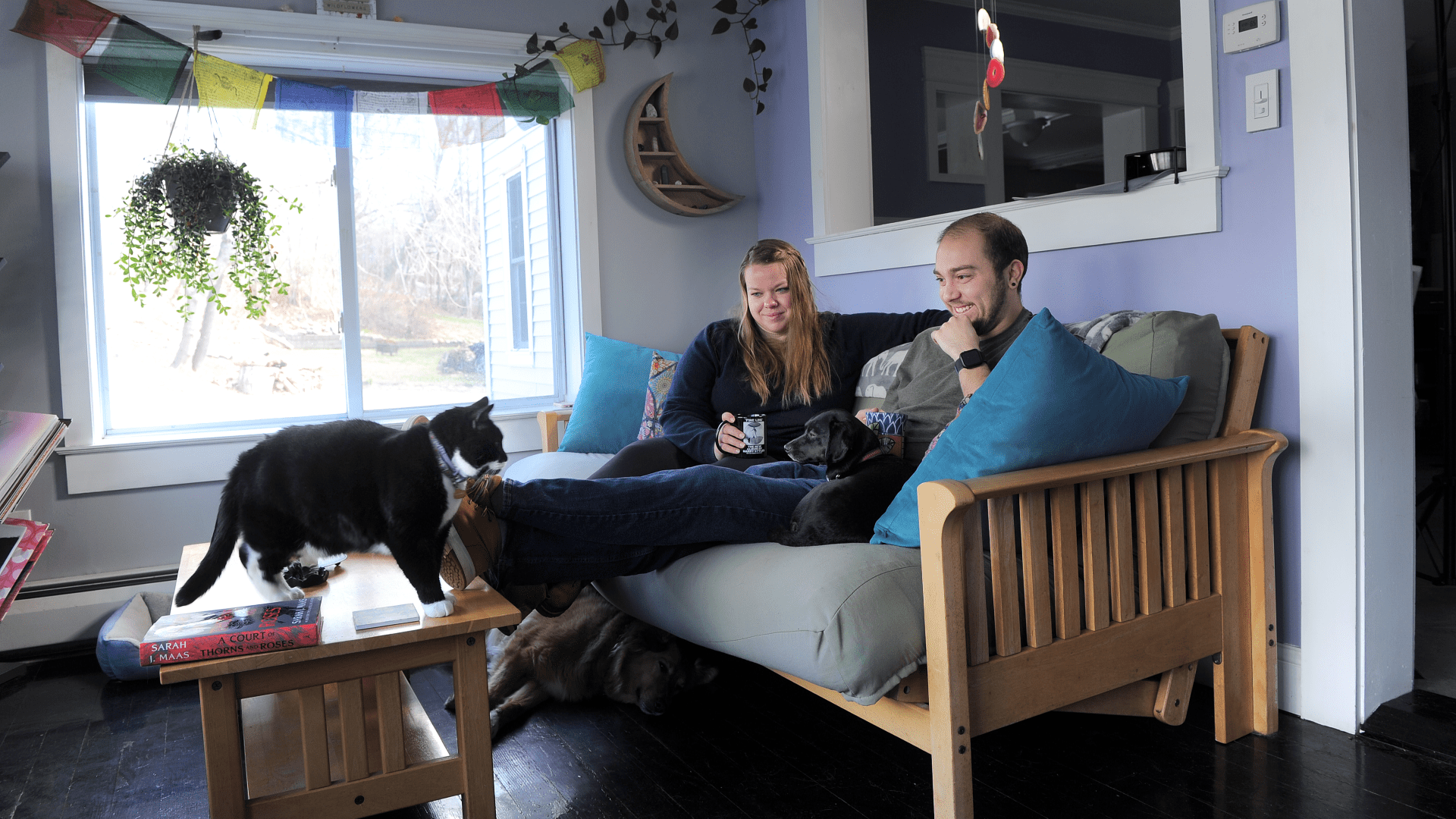

On an April morning, sunlight streamed into the sunporch of Casey and Aiden’s home. The couple sat on a futon with their dogs Winne and Olive snuggled next to them. They sipped coffee and talked about buying a bigger home when they start a family.

Though Aiden will continue his testosterone treatment for the rest of his life, he decided against the expensive and invasive gender-affirming or sex-reassignment surgery. To conceive children, the couple said they will either use a sperm donor or in-vitro fertilization. Adoption is also a possibility.

“It’s something I’ve always wanted, a family and children of my own,” Aiden said. “I want to be a good dad and role model for my kids.”

It is this scene, an ordinary Saturday morning talking about his future family, that Aiden wants younger trans people to see. It is a vision that he wishes his younger self could have imagined when he stood on a dam ledge desperate and out of hope.

“For a long time, I didn’t know if anyone would really love me the way that Casey does,” he said. “But she proved me wrong. She showed me that there are people out there who really want you to be a part of their family and their life.”

This series was financially supported by The Bingham Program and the Margaret E. Burnham Charitable Trust. We encourage you to share your thoughts on this series by visiting this page. Barbara A. Walsh can be reached at gro.r1754663831otino1754663831menia1754663831meht@1754663831arabr1754663831ab1754663831.