During the height of the protests over the police killing of George Floyd in May, Rose Barboza felt conflicted. She wanted to join the demonstrations but had a 4-year-old at her Saco home and was concerned about catching or spreading the coronavirus. Instead, Barboza began to consider another way to fight — using her purchasing power.

Online directories popped up nationally, spotlighting Black-owned businesses and educating people about how seeking out these businesses can help, at the local level, reduce the racial wealth gap, support entrepreneurship and job creation for Black Americans, and send a message that representation matters.

But, companies in Maine remained largely off the lists. Maine is the nation’s whitest state, with nearly 95 percent of its population identifying as white.

Barboza discussed this on a hike with her brother.

“And then — BAM! This idea came,” Barboza said.

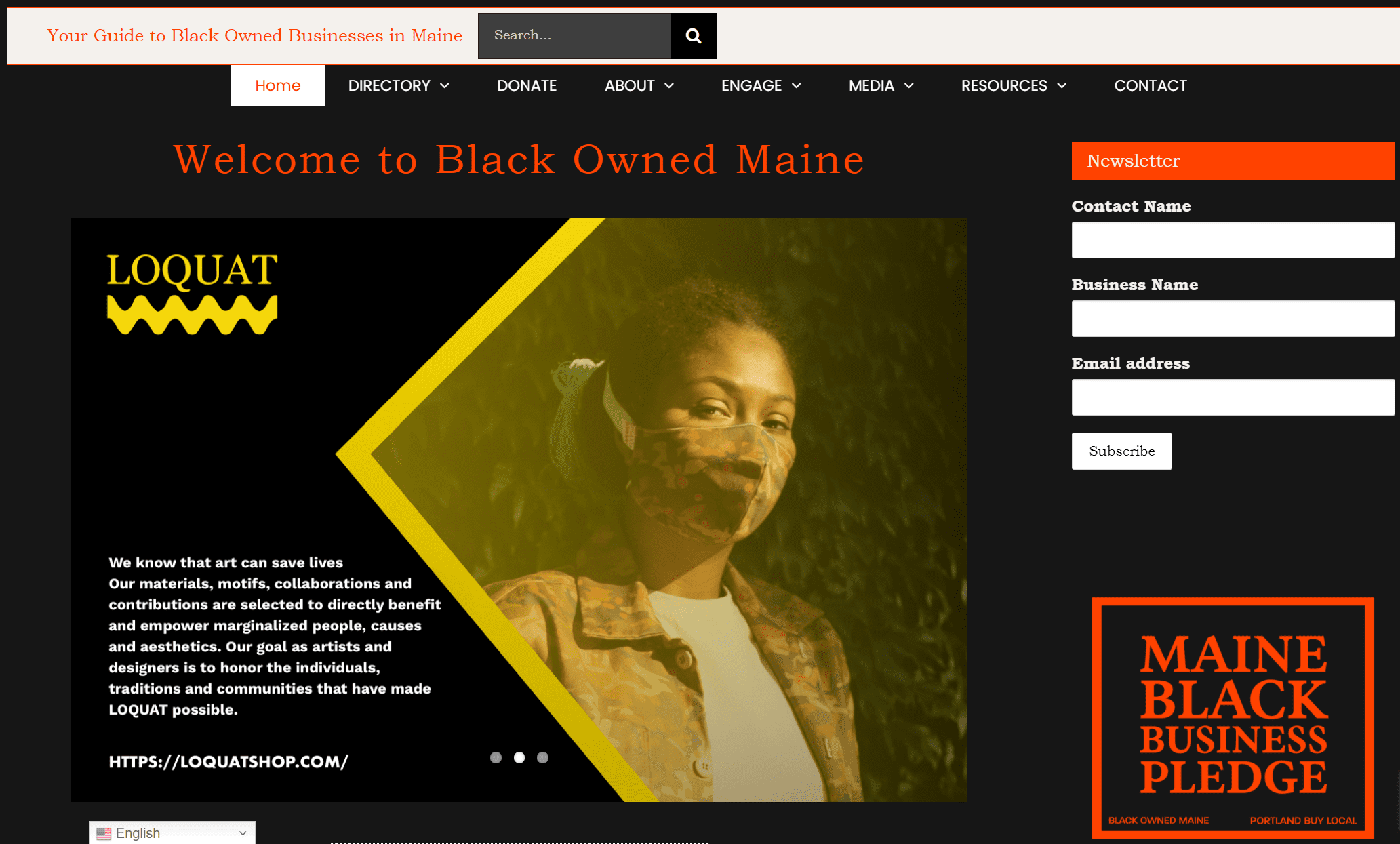

Two days later, on June 1, she launched Black Owned Maine, or BOM, a virtual directory of businesses in the state that are at least 50 percent Black-owned.

Barboza, a recent University of Southern Maine graduate with a degree in marketing and international business, had been furloughed from her job in the travel industry and was brainstorming ideas for her own venture. She wanted to build a website and considered opening a marketing agency.

“I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, this is all of that in one thing,’” Barboza said. “I finally found my niche. I finally found the thing that I can focus my energy on and it’s something that I know about already. I can list 100 (Black-owned businesses) off the top of my head.”

She enlisted the help of her friend, Jerry Edwards, a Portland music producer who goes by the name of Genius Black. The directory swelled.

Black Owned Maine now lists more than 250 businesses, nonprofits and contractors; 14,600 Instagram followers; and a podcast. Barboza said events and a clothing line are in the works.

The group also raised $50,000 in four months, and began awarding innovator grants for listed businesses looking to rebrand and family grants for households struggling to pay bills because of the pandemic. Barboza, who had to return to work July 1, was able to quit her job in October to work on the site and its projects full time. Now she is looking to help build online presences for micro-businesses that may not have websites.

While a few question whether the directory is necessary, supporters say highlighting Black-owned businesses benefits the state’s economy and enables people to counteract some economic racial disparities.

Barboza, who is of mixed race and grew up in Lewiston, said Black businesses tend not to be part of the mainstream, often do not come up high in internet searches and sometimes cannot afford to advertise on traditional platforms. Giving them exposure in the directory helps broaden their customer bases and gets consumers thinking more consciously about their spending decisions.

Rebeccah Geib, an ultra-runner, credits Black Owned Maine with helping her find The Exercise Design Lab in Bar Harbor, where she lives. Jacques Newell Taylor opened the business in 2019 after running his own exercise studio in Los Angeles for 15 years. Taylor specializes in designing customized exercise programs that integrate neuroscience to help improve brain health and athletic performance.

Geib was surprised she had never heard of the business, especially because it aligns so well with her lifestyle, values and needs as an athlete.

“How was it possible that as an athlete and just an overall fitness nut, I had no idea that this business even existed, and I had no idea who Jacques was?” she wrote in an email, noting that Bar Harbor has a small year-round community.

Geib, who is white, said it’s not just the physical gains she’s made that keeps her coming back to The Exercise Design Lab, it’s the conversations she has with Taylor about race and community.

“I train with Jacques because it’s one of the most enriching experiences I’ve ever had,” she said, “and without Black Owned Maine, who knows how long it would have been before I discovered (him).”

Geib said she always thought that she was a person who supported racial justice, but realized while attending a Black Lives Matter rally that showing up at a protest was not enough: she needed to take action.

“Black Owned Maine is now this tangible resource to use in order to take a step toward being an ally,” she said.

One challenge Taylor has faced is the independent mindset locals have about exercising: they hike, bike, run and go to the gym, he said, but are not as adventurous when it comes to trying a new approach.

But being on Black Owned Maine has already gained him four clients in addition to Geib. They too had been to a Black Lives Matter rally and decided to follow up. They found The Exercise Design Lab on the site, checked out the program and were intrigued.

“Now they’re all here, every single one of them,” Taylor said. “I was moved in many ways that people who don’t have to, actually made a conscious effort … to support Black-owned businesses.”

Being listed on the site also has led to conversations that were “prickly and uncomfortable” with a few other clients who said they do not consider race when making decisions about products and services, and questioned how drawing attention to race is helpful.

“But I’m OK with that,” he said.

Pointing to studies showing that diverse teams outperform non-diverse teams in sports, academics and business, Taylor said part of his mission is “to help communities recognize that the idea of diversity is not just a nice thing to do, or even just the ‘right’ thing to do; it’s the thing to do if we really do want to push ahead and prosper, and have opportunities for future generations.”

He sees the directory as especially important for a state like Maine.

“This idea that you have this website, this listing that is saying, ‘Hey look, we’ve got some diversity here,’ is going to be really important to attracting other people of different backgrounds to come and say, ‘Well they can do it, maybe I can do it. Maybe there’s some opportunity there.’”

Genius Black, who grew up in Texas and attended Bowdoin College in Brunswick, echoed this in a recent BOM podcast.

“Black Owned Maine as a directory and a resource and as a brand is also helping the state of Maine stand up and represent itself as a place that does have people of color, does have Black people, does consider diversity,” he said. “We’re going to bring money to this economy; people who wouldn’t have felt comfortable coming here and spending their dollars and voting with their dollars.”

Taylor said he’s looking forward to connecting with other Black business owners in the state through events or meetings hosted by BOM. He’s already used the resource to find and visit another Black business on Mount Desert Island: the Quietside Cafe in Southwest Harbor.

Ultimate Car Care in Portland is also listed on the site. Its owner, Joe Kings, said he’s pleased there’s a directory to help Black businesses connect. He was part of a group that attempted to start a Maine Black business alliance about 20 years ago that never went anywhere.

“We met in meetings and talked about it, but we just never could get it off the ground. So we just walked away from it,” he said. “But I’m very proud of (BOM) being out there now.”

Kings said he has been involved in many projects over the years dedicated to helping Black-owned or minority-owned businesses stimulate the economy and thrive. Ultimate Car Care has funded Portland’s Juneteenth celebrations for 23 years.

He couldn’t tell if being listed on the site has brought in more business because he’s always been busy. He said he has a customer base that extends to Augusta and beyond and is often booked three weeks out.

“We’ve been doing this for about 25 years, and people just kind of know where to go,” he said. “It’s hard to say (whether being listed on BOM has had an effect) because it just never stops.”

Shawn Garner of Lewiston said highlighting successful Black businesses like Kings’ is important to inspire young Black entrepreneurs who may be surrounded by negative influences like he was, growing up in a high-crime area of Florida. Almost four years ago he ended up staying in Maine after what was supposed to be a short visit. The people he was traveling with left him behind.

“When I came up here, I didn’t know heroin was as big as it was, and I don’t do (hard) drugs because I’m an athlete,” he said. “He had laced a blunt with heroin. I wanted to fight him, and so he told me to catch a bus back to Florida.”

Garner had no money for the trip so he started working at Hannaford in Gardiner, and for a while lived at Trinity Men’s Shelter in Skowhegan. During that time, Garner kept telling himself he could “do better, be better.” So he decided to start his own business.

Outside of his various day and night jobs — working security at bars in Portland’s Old Port, as a manager at Hannaford and now as a FedEx driver — he has built a clothing design business, Upstylish, specializing in shirts with inspirational quotes, and now face masks.

Garner mainly advertised by word of mouth, handing out business cards and wearing his T-shirts to the gym or his security jobs. When Barboza heard his story, she asked him to join Black Owned Maine and is now helping him find stores that will carry his clothing.

Garner said he started Upstylish to show people who grew up in situations like his that there are options outside of crime. He sees Black Owned Maine as furthering that mission.

“A lot of people from my neighborhood were either selling drugs or killing people or robbing people,” he said. “Having the website of Black-owned businesses of Maine can show a lot of young Black entrepreneurs that … you can make money other ways, by being an entrepreneur, having a rap career, anything that you’re good at.

“Everybody’s born with a gift. That’s what Black Owned Maine does. It teaches young Black entrepreneurs to thrive in their own gifts.”

Another successful business listed on Black Owned Maine is Mogadishu Business Center and Restaurant in Lewiston. Its owner, Shukri Abasheikh, came to the United States from Somalia, where she had her own store, but lost it with her home during a civil war. She lived in Atlanta, then moved to Lewiston in 2002 with a wave of Somali arrivals.

Tensions were high that year. Then-mayor Laurier Raymond wrote an open letter asking Somali people to stop coming and said resettling them was straining the city’s resources. A white supremacist group protested in the city. At the time, Abasheikh defended herself and her fellow Somalis.

“I say ‘No, we do not come for welfare, we come for work, we come for peace, we come for education,’” she said. “My dream is I work and my children get education.”

While obstacles remain, there has been an outpouring of support for immigrants in the last 18 years, and studies show the economic benefits they brought to the area.

In 2006, Abasheikh was able to open the Mogadishu store after working as a high school janitor and at L.L. Bean. She has put the struggles of her early days in Lewiston behind her.

“Everybody (likes) me,” she said. “They call me Mama Africa, Mama Shukri. We cook Somali food, we cook Somali tea. They come in, Black and white — everybody … (They’re) happy, they try the food, I explain the food, they buy.”

Abasheikh said directing support on Black businesses seemed unnecessary to her, especially as businesses with owners of all races are struggling.

“Everybody needs support, not only Black businesses,” she said. “When (the coronavirus came) everybody (slowed) down, a lot of stores closed, Black and white, and everybody needs help.”

Barbazo and Genius Black agree.

“That’s something we keep pushing every day,” Barboza said. “Small business, whether Black-owned or not, is the driving force of the economy, especially here in a small state.”

Barboza is compiling a directory of resources for the site that she hopes will be accessed by anyone, regardless of race, who wants to open or grow a business in the state.

“By teaching people to focus on local Black business, we’re teaching them to focus on local business in general,” Genius Black added. “Black Owned Maine is really about supporting the economy of Maine.”

But data shows the pandemic is hitting Black people especially hard. In June, Maine had the highest racial disparity in COVID-19 cases, with Black residents contracting the virus at 20 times the rate of white residents. While Black Mainers made up less than 2 percent of the population, they accounted for more than 22 percent of the positive cases. Most of those cases came from immigrant communities where it was more common for people to live in crowded apartments without the ability to isolate, and to work in front-line jobs.

Now, with cases spiking throughout Maine, that disparity has dropped, but Black people are still affected at a disproportionate rate. As of Nov. 20, they made up 11 percent of COVID-19 cases in the state.

The economic impacts of the pandemic also have been greater and persisted longer for people of color, James Myall of the left-leaning Maine Center for Economic Policy, reported.

Based on his analysis of the latest U.S. Census and Maine Department of Labor data released Oct. 20, Myall found that different racial groups in Maine started with low unemployment before the pandemic, but unemployment among the Black workforce showed the greatest increase, peaking at about 30 percent in May, compared to 15 percent for the white unemployment rate. In August, 15 percent of the Black workforce was still unemployed compared to 6 percent of the white workforce.

A recent survey of immigrant business owners conducted by ProsperityME, a nonprofit dedicated to helping immigrants and refugees in Maine achieve financial stability, raised some red flags for its executive director, Claude Rwaganje.

Of 250 immigrant businesses the organization tried to contact — many Black-owned — only 125 were reachable. Of the 125 respondents, 60 percent did not apply for Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans, and Rwaganje said few applied for Maine Economic Recovery grants. He cited lack of information or assistance, language barriers, or incomplete record keeping and licensing as barriers to applying for pandemic relief.

Small Business Administration data on PPP loans awarded through Aug. 8 is not complete when it comes to the race of recipients. Only about 2,500 of the 25,279 grant recipients listed answered the optional question on race. Of those that did, only 11, or 0.4 percent, indicated they were Black.

“I’m concerned that the fact that the majority were not able to submit a rapid response or recovery grant request,” Rwaganje said. “That is a warning for me, to see how they’re going to survive beyond this pandemic.”

ProsperityME plans to conduct a more comprehensive survey to understand the impacts of the pandemic on Black immigrant businesses.

COVID impacts aside, many who use Black Owned Maine’s directory are looking to support Black businesses as a way to counteract some broader racial disparities that persist.

“Something that gets overlooked is that it’s not just about stopping a bad thing from happening,” Genius Black said. “It’s about counteracting the bad things that have been happening.”

In Maine, over 53 percent of Black children lived in poverty compared to approximately 15 percent of white children in 2017, and only one-quarter of black people own their own homes, compared to three-quarters of white people. Black Mainers are 6 times more likely to be incarcerated than white Mainers and Black students are 2.4 times more likely to be suspended from school in Maine than white students, according to another report by Myall.

“What we find about why people support Black Owned Maine and think about supporting companies like ours is that it’s a way to protest,” said Genius Black. “It’s a way to say, ‘I’m going to use my resources, I’m going to use whatever I have to (make) change. The economy’s going to flow regardless, so I’m going to make sure that it’s flowing through Black folks.’”