Sage and sweetgrass-scented smoke rose over the reservation, marking the deaths.

Across Indian Township, the sacred fires burned to honor the spirits of the Passamaquoddy tribe. Young and old gathered to pray outside homes where families kept vigil over the deceased.

The Passamaquoddy people took shifts tending the fires that burned continuously over two days. But this past January, tribal members struggled to maintain their tradition.

In one week, the tribe lost four members from the Indian Township community of 1,500.

Three of the four deaths were young and middle-aged men who overdosed on drugs.

“We’ve never had that many die of overdoses in a week,” said tribal police chief Matthew Dana. “The overdoses have increased dramatically. With the pandemic, people aren’t able to gather with groups or reach out. The isolation, anxiety, depression are all connected to the increased use of substances.”

Indian Township’s losses mirror Maine’s dramatic spike in drug deaths. In 2020, 503 people died from drug overdoses, a 25 percent increase from 2019, according to reports from the attorney general’s office. In January 2021, the toll rose to 58 deaths, a record loss for one month.

Tucked in the northeastern corner of Washington County, Indian Township is one of two Passamaquoddy reservations in Maine. Part of the Wabanaki or “People of the Dawnland,” the tribe once thrived on fishing and hunting. Now it wrestles with poverty, despair and addiction. Nearly half of its population, according to the reservation’s 2014 comprehensive plan, live below the poverty level. The average income is one-third less than that of Washington County, one of Maine’s poorest regions.

The pandemic has deepened the despair on the remote reservation.

“It seems like the only gathering that we are doing is for deaths versus gathering to prevent overdose and death,” said Merlin Francis, a nurse practitioner for health centers at Indian Township and its sister reservation, Pleasant Point. “It’s like a Catch-22. We’ve got to isolate because of the pandemic, but the isolation is driving up depression and overdoses.”

Pleasant Point, which has a population similar to Indian Township’s, also lost three people to overdoses this past winter, said Francis. The overdose deaths on both reservations have affected everyone in the tribal community, where families are bound by their Passamaquoddy heritage and ancestry.

“It’s been a huge, huge hit,” Francis said.

As access to the clinics and medical care grew restricted during the pandemic, Francis saw patients slip from sobriety, especially those who were new to the reservations’ Medication-Assisted Treatment program in which patients receive counseling along with Subuxone, a drug used to relieve opiate cravings or withdrawals.

“Resources were stretched,” Francis said. “Access to medical care and counseling was limited to Skype or the phone.”

Like many people who overdosed in Maine during the pandemic, several members of the Passamaquoddy tribe died while taking opiates laced with fentanyl.

“They might think they’re getting benzazepine, and it’s laced with fentanyl or heroin,” Francis said. “Then it becomes a toxic cocktail.”

While Maine distributed nearly 56,000 doses of the overdose reversal drug naloxone to police, paramedics and community members in 2020, the pandemic has hindered the process of preventing tragedies.

“If someone is isolating while they are doing drugs, there is no one to call 911 or administer Narcan to reverse the overdose,” said Abby Frutchey with Community Caring Collaborative in Machias.

And isolation, medical experts say, is deadly when someone has overdosed on fentanyl. An overdose can happen within minutes after taking the potent synthetic opiate, and the window to reverse it spans five to 15 minutes.

The reservations’ surge of drug deaths illustrated the larger epidemic in Washington County, where drug overdoses doubled during the pandemic.

“We went from 10 deaths in 2019 in Washington County to 20 overdoses in 2020,” said Frutchey, who educates organizations on how to reduce drug deaths and support recovery. “The deaths increased by 100 percent.”

In a remote county with about 32,000 people, the losses are felt much more deeply, Frutchey said, than in an urban area.

“I’ve lived in Washington County my whole life, and we are so intertwined and connected,” Frutchey said. “The loss of people to overdoses leaves a traumatic scar on our communities.”

…

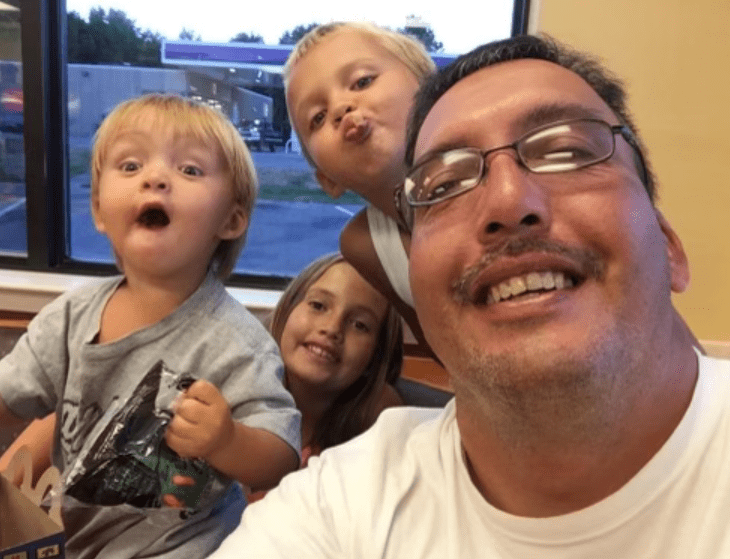

Stephen Louis Newell II was one of the tribal members who overdosed the first week of January.

Like many people on the reservation, Newell’s anxiety and depression increased during the pandemic. In the weeks before his death, Newell, his ex-wife Keya Smiley said, overdosed twice and was brought back to life with naloxone.

“Then the third time,” she added, “he passed away.”

Newell died Jan. 9, the first of three Passamaquoddy from Indian Township to overdose that week. He was 45 and left behind three children.

As a sacred fire burned outside his family’s home, Smiley wrestled with her emotions.

“It’s been hard,” she said. “I have a lot of mixed feelings, sadness, anger. He was trying and interacting, and we thought he was doing better.”

Newell, Smiley said, struggled to stay sober during the 13 years they were together.

“But he kept relapsing,” Smiley said. “I knew I had to separate from him for my own good.”

Smiley knows what it is like to live a life shadowed by addiction. She grew addicted to oxycontin in her 20s. After using methadone and Suboxone to wean her opioid cravings, she is now drug free.

“I know what it’s like to do drugs and become lost,” she said. “I’ve been clean six years, and I’m proud of that.”

In between his bouts with addiction, Newell sought solace in nature. He hunted in the woods of his tribal lands and fished in the pristine waters that surrounded his childhood home. He was a talented carpenter, earned degrees in business management and office information systems, and considered his three children the “greatest accomplishment of his life.”

Newell also worked nine years in Washington County Community College’s TRIO Student Support Services program but lost the job, Smiley said, due to his substance use.

“He was a really smart man,” she said, “but he couldn’t live without his medications.”

During Thanksgiving and Christmas, Newell spent time with his children.

“He would come by and still be part of our family,” Smiley said. “But he was pretty much homeless, couch surfing at friends’.”

Since Newell died, Smiley shoulders more burdens alone. She works full time at Indian Township’s census office, keeping track of the tribe’s births, deaths and other statistics.

On a blustery spring afternoon, the Passamaquoddy flag flapped in the wind as Smiley ended her day at the tribal office. Logging trucks rumbled past Route 1, while she headed home to her children and the small three-bedroom house that is minutes from her job.

The family’s chickens roamed the yard and a puppy barked as Smiley entered her home. Newell bought the small hound-terrier for his daughter before his death. Smiley’s three children gathered in the kitchen to greet their mother. Portraits of the family smiling with their dad hung on the living room wall.

Linda, the eldest, is 15 and looks after her brothers while her mother works. She is a student at Woodland Junior-Senior High School in the nearby town of Baileyville, where a classmate killed himself in February. The 14-year-old’s death was one of four suicides over a two-month span in the county’s northeastern region.

The young girl is old enough to understand the toll of addiction and despair in her community. Seeing tribal members “messed up” on drugs and alcohol angers her.

“She hates it,” her mother said. “She doesn’t talk about her father’s death. I think she’s trying to block it out.”

When Linda offers memories of her father, her brown eyes fall to the floor. Her voice is flat, heavy with loss and resignation.

“We’d see him and then we wouldn’t,” she said. “I miss his text messages. He’d ask how I was doing. He’d tell me, ‘I love you.’ ”

Newell’s sons Stephen III and Nitap do not offer words about their dad. Stephen is 11 and Nitap is 7. The boys spend most of their time at home and have lost interest in learning. Their classes at Indian Township School have been remote since March 2020.

“Stephen wants to sleep all day because he’s depressed,” Smiley said. “He’s not interested in doing his schoolwork.”

Her younger son Nitap has trouble sitting still and focusing during online classes.

“I’m doing the best I can,” Smiley said. “I can’t be home with them while working full-time. I’m trying to make a better life for my children, but living in poverty with addiction and alcoholism all around makes it hard.”

Not long after the pandemic began, Smiley sought counseling for herself and her eldest son to help relieve their anxiety and depression. Like many people needing help in Washington County, they were put on waiting lists.

A few months after Newell died, Smiley and her son began seeing therapists.

“We were put to the top of the list after his death,” she said.

As the days grow warmer, Smiley hopes to take her children fishing and hiking. Like her ex-husband, she seeks solace in the lakes, streams and forests that surround the reservation. Nature helps calm her anxiety and fears about her children’s future. Though they know drugs “are bad,” Smiley said, they live in a community beleaguered by loss. She does not want them to be lured into a cycle of addiction.

Soon to be 41, Smiley is resolute about remaining sober and providing her children with a good role model.

“It’s been four months and I’m still shocked about Stephen’s death,” she said. “He was my husband, my best friend most of my adulthood. But I guess there is a purpose for everything, and my purpose is to lead my kids and try to break the cycle, to educate others that there is life after drugs.”