Regulators were up to their ears in trash talk on Thursday morning as they deliberated over a draft of rules intended to increase recycling, reduce the amount of material going to landfills and ultimately reduce the amount of packaging that’s coming into the state.

It’s been five years since Gov. Janet Mills signed a resolve directing the Maine Department of Environmental Protection to come up with the rules. I remember the first meeting I sat in on where they were explained, on a chilly January afternoon at a community center in Ellsworth.

The room was packed, and then-state Rep. Nicole Grohoski, who had long been championing the concept, was trying to get residents on board.

Ellsworth was a particularly interesting place to be reporting on trash at the start of 2020. The long-awaited waste-to-fuel plant in Hampden, where Ellsworth and more than a hundred other municipalities were planning to take their waste, had finally opened after more than a year of delays (it lasted less than a year before shutting down).

The nearby incinerator in Orrington, where trash was burned to generate electricity, was still operating, but at reduced capacity, having lost many of its contracts when it raised rates and the Hampden plant came on the scene.

Meanwhile, it had been two years since China implemented its National Sword program, which banned many recyclables and put a contamination limit on others, throwing recycling markets in the United States into chaos.

Before the implementation of the program, the Environmental Protection Agency estimated that our plastics recycling rate was roughly 9 percent, in part because we sent a lot of it to China.

After National Sword, according to research from an environmental group affiliated with Bennington College, that figure dropped by half, to around 5 percent. That means 95 percent of the plastics generated that year were put in a landfill or burned for energy.

Meanwhile, the per capita generation of plastic waste has gone up 263 percent since 1980.

Hancock County exemplifies many of the challenges of recycling and waste management across the state. It’s both urban — the town of Ellsworth is the service provider for the area and the gateway to Acadia National Park, which saw more than 4 million visitors last year — and decidedly rural.

It’s also seasonal, with the volume of waste exploding in the summer and dropping off significantly in the winter. The rural nature of the region means transportation costs are higher than they are in more densely populated areas, and the seasonality makes it tough to maintain infrastructure that must handle fluctuating volumes.

In 2019, The Ellsworth American, where I was a beat reporter at the time, chronicled the situation as town after town cut back on recycling or stopped their recycling programs entirely, citing skyrocketing tipping fees and a lack of end markets.

“We just don’t get enough material anymore to make it worth it to keep operating,” Joyce Levesque, manager at Coastal Recycling, which served five towns before it closed in 2019, told The American. “Recycling isn’t cheap, so it’s either everybody or nobody doing it.”

The draft rules presented at the meeting of the Board of Environmental Protection on Thursday are intended to get everybody to do it. But some board members were skeptical that they would have the desired effect, at least as currently written.

“It’s not going to incentivize anybody to move their solid waste,” said board chair Susan Lessard, who also serves as town manager in Bucksport.

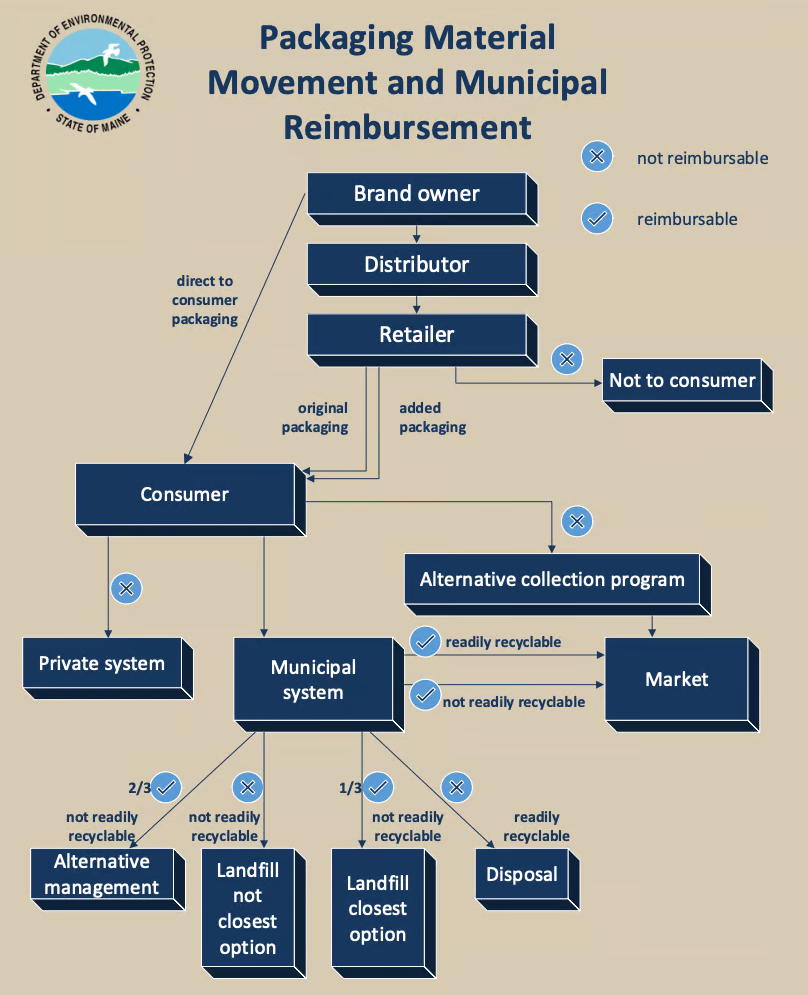

Under the proposed rules, communities would be reimbursed for both recycling packaging and for diverting it from landfills by choosing options higher up on the solid waste management hierarchy.

If a municipality sends packaging material that isn’t readily recyclable to a landfill when an incinerator is closer, they’re not eligible for reimbursement, explained DEP staff on Thursday.

What if there isn’t an incineration option, wondered board members — say an incinerator is full, and can’t take any more, or it isn’t currently operational, as is the case in Orrington.

Would the municipality be dinged for an option it doesn’t have? Yes, as currently proposed, said Elena Bertocci of the DEP.

“That is something we thought about a lot and tried to figure out if there was a good way to do something different. In many cases it’s not going there because the municipality doesn’t want to pay for it at the end of the day.”

Bertocci said it also became complicated to try and “put lines around” what not having access to an incinerator looks like.

The rules would also reimburse communities at a higher rate for incinerating over landfilling, which some board members argued meant communities in southern Maine with more options and access would get reimbursed at a higher rate than rural areas.

Municipalities that choose incineration, for instance, would be reimbursed at two-thirds the average cost of recycling readily recyclable packaging material. Those that send it to landfills (if that’s the closest option) would be reimbursed at a one-third rate.

“Our cost is not the same as someone in southern Maine,” said Lessard. “For those of us with no option close enough… you only get one-third just because there’s nothing closer. But communities within proximity that can do that get two-thirds.”

Reimbursement at the higher rate likely won’t offset the cost of trucking packaging that isn’t easily recycled to places like the ecomaine incinerator in Portland, said Lessard. “Transportation cost alone is the killer.”

The rules are still being drafted, and there’s room for change. They’re intended to incentivize infrastructure development that will make it easier and more financially attractive for rural communities to divert from landfills, DEP staff said Thursday. But that will take time.

“I see this as good, in terms of trying to put the materials in the place they need to be over the long term,” said Steven Pelletier, a board member from Topsham. “But I see this proximity thing as being something that could really kind of shake up this particular industry… what we’re seeing on the ground now — in terms of facilities we can bring things to — in 10 years would be totally different, I would think, because of this.”