The Wolfden Resources Corporation is making plans to mine for silver in Pembroke, but residents of the Washington County town near the Canadian border are fiercely against the idea and packed a public hearing last week to voice opposition.

“This is going to affect all of our people here in this territory,” said Dwayne Tomah, an area resident and Passamaquoddy tribe cultural historian. “We have a lot of fishermen here, we have to drink the water, we have to gather our plants, we have to gather medicines … (Wolfden is) coming into an economically depressed area and exploiting our mother.”

Sentiment at the 2 ½-hour meeting was overwhelmingly in favor of a proposed ordinance banning industrial-scale metallic mining in the town.

Wolfden is the first company to attempt mining in Maine since the state passed new regulations in 2017. The Canadian company, which has yet to successfully develop a mine, pulled back on plans to mine in the Penobscot County town of Patten after state regulators said they would reject its application for a required rezoning, in part because it “contain(ed) numerous errors, inconsistencies, and omissions,” according to a staff memo. Many hailed the state’s new rules as the nation’s most stringent, particularly regarding water quality.

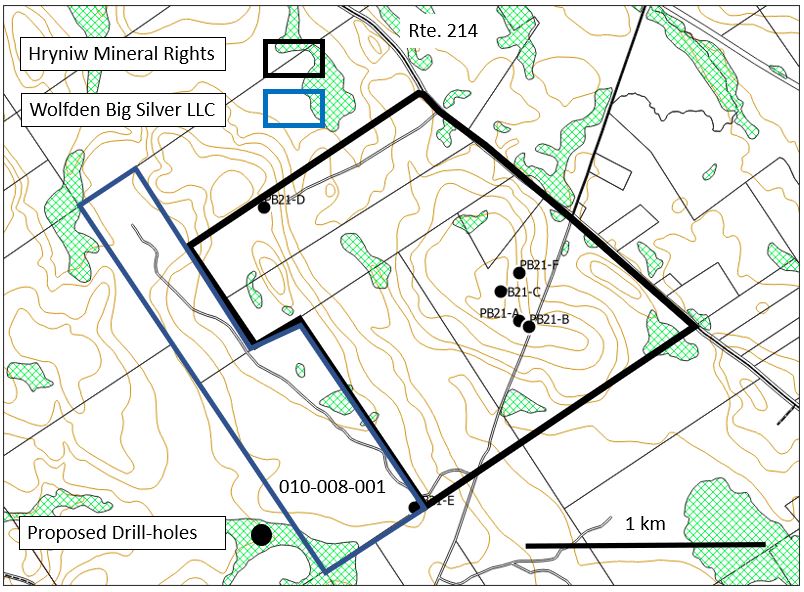

But Pembroke residents, who depend on the area’s rich water resources for drinking, recreation, tourism and their livelihoods, expressed concerns that the company would not be able to ensure the safety of the region’s environmental assets, even under Maine’s strict rules. A map prepared for Friends of Cobscook Bay, one of the groups opposed to the project, shows several aquifers and high-quality brook trout habitat not far from the exploratory drilling site.

“They cannot protect the water for you,” said Ralph Chapman, a former state representative from Brooksville, host to the defunct Callahan Mine, which is now a Superfund site. “Don’t expect that the state regulations are going to be something that will keep your water clean.”

Some of the gravest environmental concerns in mining revolve around the extraction of base metals — such as copper, lead and zinc — that often occur in bands of rock rich in iron sulfides. Iron sulfides that are exposed to air or water create sulfuric acid, which can pollute waterways for decades, a phenomenon known as acid mine drainage.

The Pembroke mining site has been dubbed “Big Silver.’’ Wolfden has conducted exploratory drilling for silver, lead and copper at the site since the fall, digging eight holes down 2,600 feet, according to figures presented Wednesday. The area, roughly two miles north of Pembroke village, where the Pennamaquan River drains into Cobscook Bay, was the site of limited mining in the late 1800s and has been sporadically searched for minerals since the 1960s.

Wolfden representative Jeremy Ouellette pointed out that minerals and metals are essential to modern life, which was evident in the many residents filming the meeting on their smartphones or the dozens of cars in the parking lot.

“We all use these minerals, and we have to do it in the most ethical and responsible way,” Ouellette told the standing-room only crowd. “What better way to do that than by controlling it in our own towns and communities?”

“It’s already under control because there is none,” a man shouted. “Go back home.”

Silver is most often used in industrial applications, where it can produce smooth, leak- and corrosion-resistant joints, and is important in the production of airplanes, automobiles and photography equipment. Smartphones do contain some silver: an experiment at the University of Plymouth in the United Kingdom found that a typical smartphone contains roughly 90 mg of the metal.

A vote on the Pembroke ordinance will be held May 4. If passed, it would prohibit industrial-scale metallic mineral mining, defined as any operation that is more than 3 acres or extracts more than 10,000 tons of mine waste per year, or any operation that extracts more than 10,000 tons of bulk sampling material during exploration.

The new regulations would not affect gravel pits, or the excavation of sand, fill, clay or any other non-metallic mineral excavation, and would be retroactive to Dec. 20, 2021.

Ouellette told the crowd that while initial testing at Big Silver has shown “positive results,” what the company has found so far is “not high enough grade and high enough volume in order to justify a mining project.”

“We are excited by those results,” Ouellette continued, “but there’s not a feasible project out there that’s been defined.”

Several residents felt the picture was less rosy than the one Wolfden painted to investors in a recent press release, in which the company’s vice president of exploration, Don Dudek, said “We are very encouraged by the grade and size implications of this silver-rich mineralization system … Our goal is to discover and delineate an underground resource of 20 million tonnes or more, which appears achievable with this type of mineralized system.”

Wolfden filed a work plan with the Maine Department of Environmental Protection last June to begin exploratory drilling at Big Silver. State agencies do not require a permit as long as the test pits have surface opening areas no larger than 300 square feet. For work beyond that, Wolfden would have to apply to the DEP for advanced exploration permits, under which they could remove no more than 10,000 tons of mine waste.

The next step would be to obtain a full scale mining permit from the DEP, which would take years. The company would be required to submit a raft of information, including two years of local water quality monitoring data and plans to return wastewater discharge at water quality levels equivalent to or better than natural groundwater. There would also be extensive public input.

Those in favor of the ordinance, however, worried that once a permitting process had begun, it would be difficult to stop. Maine law allows municipalities to enact more stringent regulations than what’s on file with the state, and if the ordinance passes on May 4, the company would be forced to abandon any industrial-scale mining plans for Big Silver.

Silver production is not big business in the United States, which extracts just 4% of the world’s supply, mostly from mines in Alaska, Nevada and Arizona.

China controls most of the world’s mineral extraction and production, which has led the Biden administration to push to secure the supply chain of critical minerals for the U.S., particularly those that are key to clean energy technologies such as lithium, cobalt and manganese. None of the metals Wolfden is looking for in Pembroke are on the 2022 list of critical minerals.

Wolfden recently withdrew an application to rezone an area in Patten after Maine Land Use Planning Commission officials said they would reject it based on the recommendation of staff.

In the Patten case, a rezoning is required before Wolfden can apply to the DEP for a mining permit. No rezoning would be necessary in Pembroke. The Wolfden CEO, Ron Little, told The Monitor that the company is not giving up on plans to mine in Patten.

Pembroke had been floated as a place to bring mine waste, known as tailings, from the proposed Patten project, but Ouellette said that idea, which surfaced as part of an alternatives assessment required by the Land Use Planning Commission, had been dropped. “There’s no plan to bring tailings anywhere in this area.”

Little of what Ouellette said Wednesday appeased the crowd, which expressed deep mistrust of Wolfden. “Everyone here cares about Pembroke,” said resident Colin Brown, gesturing around the room and then pointing at Ouellette. “Everyone except this guy.”