Editor’s note: This story is part of an occasional series on the effects of the state’s pension costs.

The year is 2020, just nine years from now, and the state is facing one of its worst budget crisis in years.

A new governor and legislature are grappling with the inescapable fact that before they can spend a penny on schools, roads or welfare, they have to pay a $760 million bill — almost all of it debt from the past.

The bill has come from the Maine pension system. And if the state doesn’t pay every cent of it right on time, it will be in violation of the Maine constitution.

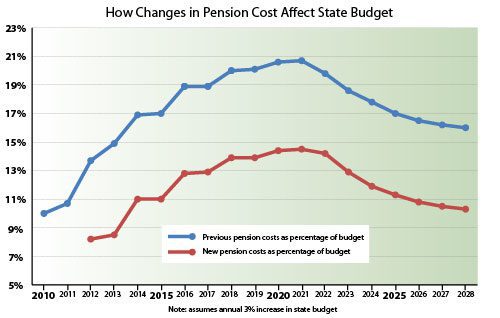

The problem: the bill eats up 20 percent of the state budget — ten times more than the court system, more than all the state’s colleges put together and nearly as much as Medicaid.

Under this scenario, the state would either have to increase taxes or dramatically cut state programs.

Until just a few weeks ago, that scenario was on its way to being reality, according to state pension and budget data analyzed by the Maine Center for Public Interest Reporting.

But a new law — LD 1043, the biennial budget bill — has created a new picture, one that promises to be better for the state’s fiscal health, better for funding state services — but worse for the 75,000 teachers and state employees who depend on the state pension system as their primary source of income in their retirement.

Former Republican state senator Peter Mills, who made pension costs one his specialties in his 16 years in the legislature, said the pension change “helps every single state budget in perpetuity … it’s a extraordinary thing.”

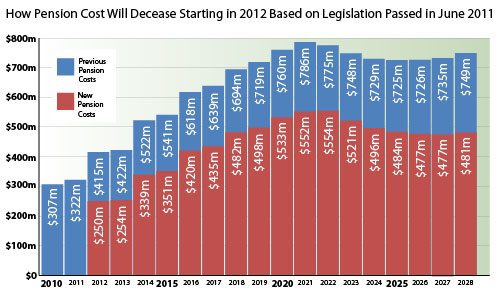

That bill — passed by a two-thirds majority vote in the Legislature and signed by Gov. Paul LePage — reduces future benefits to retirees. The reduction means that instead of the state paying $9.63 billion in pension costs between now and 2028, the cost will be $6.19 billion — a 35.6 percent smaller bill.

Looking at 2020 again, instead of a pension bill of $760 million, the bill is projected to be $480 million. And instead of representing 20 percent of the state budget (based on an annual growth rate of three per cent), the pension costs would be 14.4 per cent of the budget.

STATE RETIREES PAID PRICE

The savings come almost entirely by cutting cost of living adjustments (COLA) for state retirees.

For retirees — those retired now and in the future — the means their pension checks will lose buying power.

Previously, retirees could get up to a four percent COLA each year on their entire pension benefit, depending on inflation. Now, they will not get a COLA at all for the next three years, unless there is a budget surplus. After that, they could get up a 3 percent COLA, but only on the first $20,000 of annual retirement income, which is about the average.

For retirees on or below the average, there may not be a noticeable loss in buying power so long as inflation stays at 3 per cent of less. But a retiree with an annual benefit of $40,000, for example, would not get a COLA at all on half of his income, meaning that if inflation averages more than 1.5 percent, the value of his check declines.

That would not happen to the state employees and teachers if they were part of the Social Security system, which has a COLA on the full amount of the benefit. (The state pension system is considered a replacement for Social Security.)

State employees and teachers have the state pension system instead of Social Security.

State employees have called the changes a new “tax” on their members that was used to reduce the state budget and fund a statewide income tax decrease.

The governor, any legislators from both parties and others see it as an adjustment to benefits that doesn’t reduce retirement checks or change the eligibility rules, but was essential to putting the state’s fiscal house in order.

One non-partisan voice in the debate has been the 2010 report on reinventing state government by Envision Maine, a think tank based in Freeport. The report called Maine’s pension debt “a mess” and made cleaning it up its No. 1 recommendation for enabling the state to invest for “a new prosperity.”

Co-author Alan Caron said while his report did not recommend “charging current retirees, which is effectively what they did,” he said the governor and the legislature “overall did some good work … it’s a pretty good first step. They turned it in the right direction.”

Sen. Richard Woodbury, an independent, of Yarmouth, is the author of a study of public pensions and taxes for the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston.

He said there is “no question” that the reduction on the pension debt not only made possible the tax cut but also helped restore some funding to health care for the needy.

The reduction of the pension’s unfunded actuarial liability (UAL) from $4.1 billion to $2.4 billion “is a big positive,” he said, but, like Caron, he questioned how it was paid for. He voted against the budget bill that include the pension changes.

“The people taking the biggest hit,” he said, are retirees with high income, who he estimated will take “effectively an eight percent shift downward for their entire time of their retirement” if there is significant inflation.

One of the most widely consulted national experts on state pensions is a David Crane, a special economics advisor to California Republican Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger.

Crane, a Democrat, has written extensively about what he calls “pernicious displacement” — the hidden costs of pension debt that forces out spending on state services.

He called Maine debt reduction “meaningful” because that crowding out has been reduced by about a third.

Mills, an unsuccessful candidate for the Republican gubernatorial nomination last year, later advised LePage on the topic. After the scandal in the Maine Turnpike Authority earlier this year, the turnpike board named as the authority’s new chief executive.

Unless there is a system for new hires (one will be studied), Mills pointed out these changes effect everyone retired now, working now and planning to retire and those who will be hired in the future.

Still, he said that while the way the pension costs that were cut “were pretty rough on the retirees,” the reduction in debt is “a big story.”

A veteran Democratic member of the appropriations committee see the pension changes differently.

Rep. Peggy Rotundo, D-Lewiston, said that while it was “critically important to be fiscally responsible” and reduce the pension debt, the scope of the problem was “not as grave” as the governor and state Treasurer Bruce Poliquin made it out to be.

Stock market gains this year, she said, “are making things much better than they were.”

(The S & P Index was up 7.38 percent for the year at the time of the interview. The Maine pension system projections assumes an annual 7.25 percent return on its investments over the next 17 years.)

Rotundo said LePage’s original proposal, including reducing the state’s contribution to the pension while increasing the employees’, was “too extreme,” a view shared by most of the appropriations committee, which unanimously rejected that aspect of the governor’s legislation.

PENSIONS EFFECT BOND RATES

The pension indebtedness has two major effects on the state’s financial health health. The first is the impact on the biennial budget — eating up hundreds of millions of dollars to pay for dent incurred years ago rather than paying for services needed now.

The second is what it could do to the state bond rating — the price the state pays to borrow money for major state projects and land purchases. The worse the rating, the higher the interest rate.

A review of two noted bond rating agencies’ May reports on Maine show that the pension debt if one of a number critical comments on Maine’s fiscal condition, although there were also positive comments.

Standard & Poor’s rates Maine “AA negative outlook.” AAA is the rightest rating.

“We could lower the rating,” the report states, “if there are further significant declines in the state’s financial or liquidity positions. However, Maine began to rebuild its stabilization fund in fiscal 2010, and officials project improved liquidity and financial results for fiscal 2011. In addition, the governor’s (LePage) current proposed budget includes elements that would significantly lower many of the unfunded liabilities, and improve the financial position, although these have not yet been enacted. The outlook could be revised back to stable if Maine’s financial, liquidity, and liability positions improve through continued budget management measures and outcomes.”

Moody’s rated Maine as “aa2 stable outlook.” “Aaa” and “aa1” are higher ratings, but the ratings go as low as C.

Although Moody’s rating means the state has a “very strong capacity” to meet its obligations, among the negatives it cites is the state’s unfunded pension dent.

“Failure to adopt proposed pension reforms would lead to increased annual costs for state and teacher retirement system,” the Moody’s rating cites as one of the “credit challenges to the state.”

Two state officials in charge of the budget and debt said recent meetings with the bond rating agencies were encouraging because some of the negatives on the state balance sheet have since improved, including the pension debt.

Sawin Millett, the state’s chief financial officer, said, “I think they generally were favorably impressed with the direction we’re going in. We had strategies – I’m optimistic that we’ve turned the corner … the savings we’re achieving on the pension side, all of the structural changes we’ve made in this biennial budget, I can see the 2014/15 budget starting out without a structural gap.”

Poliquin, an unsuccessful candidate for governor who was later named by the Republican-led legislature to be the new state treasurer, has been speaking all over the state since January about the pension debt.

He called the pension changes “very, very exciting. Breathtaking in its scope. It’s huge.

“By avoiding a downgrade by a bond agency — and S&P has a downward outlook — downgrading would have cost more interest payments and a black eye. That did not happen,” said Poliquin, a former New York investment manager.

Poliquin gave as an example the recent $108 million bond for roads, public lands and other projects approved by voters in recent referenda.

If Maine was downgraded one notch, he said, the cost of the 10-year bond would have been an additional $780,000 over 10 years.

John Christie was a Reynolds Fellow at the recent pension seminar sponsored by the Society of American Business Editors and Writers.