Many states and cities — Maine and Portland included — are now in the third or fourth year of ambitious climate action plans. These roadmaps pledge steep cuts in emissions, large expansions of renewable energy, bold adaptations to guard against the effects of extreme weather and more.

But climate action is easier said than done. As communities hit the adolescence of their decarbonization and adaptation efforts, the challenges of sustained action — and the funds needed to support it — are coming into focus.

With unprecedented federal funds on the table to aid in this work, policymakers are getting increasingly creative to set themselves up for long-term climate success. Portland is considering a novel approach to help kickstart future climate work by leveraging a modest pool of existing renewable energy funding.

I covered this proposal for Energy News Network this week: Portland wants to create a “climate trust fund,” putting proceeds from the sale of renewable energy credits from city-owned solar farms (among other funding sources) toward consulting work and other up-front costs to accelerate climate progress.

The fund would include some money from “penalties paid for violations of sustainability related ordinances, private donations, proceeds from grants, and voluntary appropriations made by the Council,” wrote Portland sustainability director Troy Moon in a memo to a city council committee last week.

But most of it would come from the sale of those city-owned solar certificates, amounting to $300,000 to $400,000 a year, he said. It’s not much in the grand scheme of things, but could “provide leverage to launch” big climate projects.

One advocate I spoke to called it “seed money for larger savings.” The proposed fund could, for example, pay a consultant to write grants that would bring in much larger federal funding, or fund a scoping study of Portland school rooftops to identify the best candidates for solar arrays.

Such an analysis, paid for with benefits from early city investments in renewable energy, could help attract developers, set priorities, lower project costs and speed along construction.

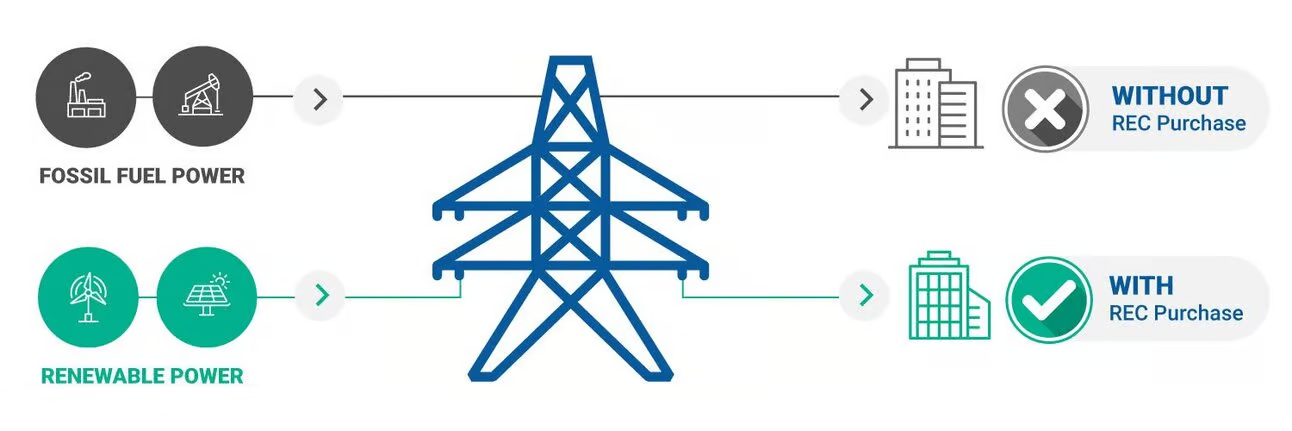

So what are renewable energy certificates or credits, also known as RECs? Put simply, they offer proof of investment in the emissions reductions associated with clean energy. A government or business can buy, trade or hold onto RECs in order to count the associated renewable energy toward its climate goals.

“RECs represent ownership of renewable electricity on a shared grid,” the Environmental Protection Agency wrote in a 2021 fact sheet.

For any year that Portland sells off its RECs from city-backed solar arrays like the Ocean Avenue landfill project, it will no longer be able to “count” the emissions reductions represented by those credits. Another entity will buy that right for its own climate goals instead.

But Portland will, in practice, still be using the renewable power generated by its solar panels, and will, in practice, still be making that progress on lowering local emissions. This is where the concept of RECs gets really tricky.

“Unfortunately, paying for RECs does not mean the energy powering a home or business comes directly from a renewable source,” the decarbonization think tank RMI wrote in 2022. “The credit only represents one new renewable MWh (megawatt-hour) generated and added to the power grid somewhere — even if that power source is hundreds of miles away — while power plants closer to home keep burning gas, coal, or oil.”

“The disconnect between clean power generation and the electricity actually used by the REC purchaser makes it difficult to account for the total climate impact of a REC,” RMI continued. “Some critics have said they play a role in corporate greenwashing, because it’s difficult to verify that purchasing RECs today leads to direct GHG emissions reductions in homes and businesses.”

It’s an example of how hard it is to really account for climate progress, while at the same time trying to drum up funding to pay for that progress to continue. But none of this is to say that selling off its RECs isn’t a good option for Portland.

“Figuring out how to have those savings not just go to the general fund, but go to a special climate fund to continue to implement climate projects, is one example of an innovative solution,” said Peyton Siler Jones, the Portland-based interim sustainability director with the National League of Cities. “It’s exciting to see that being something that can be scaled and replicated in smaller communities.”

Portland’s proposed climate fund passed the city council’s sustainability committee last week and goes next to finance. If it passes the full council, it will take effect next year.