A single week late last month offered a startling snapshot of a once-staid electrical utility industry now swept up in turbulent change:

• California’s largest utility, Pacific Gas & Electric, declared bankruptcy and faces billions in liability following the state’s 2018 wildfires.

• All-time low temperatures in the Midwest strained the capacity of its power grids, forcing utility customers to lower thermostats and temporarily close several manufacturing plants.

• In a “Worldwide Threat Assessment” report, Director of National Intelligence Dan Coates acknowledged that both Russia and China already possess the capacity to temporarily disrupt U.S. power networks.

• CEO James Robo of NextEra Energy (the nation’s largest utility) predicted that cheaper electricity from solar power and growing battery storage capacity will be “massively disruptive” and will “create significant opportunities for renewable growth well into the next decade,” Clean Economy Weekly reported.

Here in Maine, Rep. Seth Berry (D-Bowdoinham) proposed a bill to create a consumer-owned utility that would – with fair compensation – take over the electric transmission and distribution assets of Central Maine Power and Emera Maine, investor-owned utilities that transmit 96 percent of the state’s total power.

These events signal a new era for electric utilities, with threats and opportunities that challenge the industry’s antiquated mode of operating.

A well-worn business model

Following a century of steady growth, electricity sales leveled off in 2007 — a trend expected to continue, given improved energy efficiency and more on-site power generation. Flat demand for electricity benefits the environment and can lower rates, but limits revenue sources for investor-owned utilities.

There’s a concern that utilities overbuild or gold-plate their systems.”

— Gordon Weil, a utility consultant who served as Maine’s first public advocate

What buffers their bottom lines is a guaranteed rate of return (typically 9 percent to 13 percent) for infrastructure investments. Because that’s the way utilities make money, “they love to build things,” says David Littell, a former commissioner at the Maine Public Utilities Commission who is a principal at the international nonprofit Regulatory Assistance Project.

“There’s a concern that utilities overbuild or gold-plate their systems,” says Gordon Weil, a utility consultant who served as Maine’s first public advocate. CMP’s proposed transmission line through Maine, for example, is projected to net the company roughly $60 million each year. In confidential documents recently shared with the press, CMP proposed offering ratepayers annual benefits of less than a twelfth of that figure.

Investing in large-scale infrastructure assumes that power comes primarily from a few major generating stations. But the growing affordability of solar and wind technology is changing the economics of electricity generation and storage. Households and businesses now can generate “distributed” solar power that is either used on site, fed into the grid or stored in fixed or mobile (electric vehicle) batteries – which in turn can provide on-site power or help charge the grid.

Increasingly, utilities are confronted with problems that they could solve with conventional infrastructure or with distributed power sources like solar and wind. For them to choose the latter option, Littell says, “there’s a whole cultural shift that would have to occur.”

A model of innovation

Green Mountain Power, Vermont’s largest utility, is a certified B Corporation, with a commitment to environment, employees, community and governance. It actively promotes solar panels, electric vehicles and battery storage – measures that not only lower greenhouse gas emissions but also improve reliability (reduce and shorten outages) and increase resilience (the system’s capacity to bounce back from a disruption, such as a storm or a cyberattack).

Unlike Maine’s deregulated utilities, which only handle power delivery, Green Mountain Power both produces and distributes power.

It also differs from Maine’s two investor-owned utilities in being locally governed, and the vast majority of its board members are Vermont residents. (Its sole investor, an energy company in Quebec, supported its decision to become a B Corp, balancing profits with people and the planet.)

CMP is a subsidiary of Connecticut-based Avangrid, whose controlling shareholder Iberdrola is a Spanish multinational corporation with operations on four continents. Emera Maine is part of a Nova Scotia-based utility with subsidiaries in Atlantic Canada, the United States and the Caribbean.

Green Mountain Power seeks to upend the traditional model of moving electricity only from generators to users by relying on power close to the source and making its transfer more of a “data network than a one-way flow,” says Josh Castonguay, its vice president of innovation.

The utility encourages customers to install storage batteries that can be used during outages and that the utility can draw on in peak periods – to help lower costs for ratepayers. Last summer, for example, GMP was able to save its 265,000 customers $400,000 in a single day by relying on these batteries to avoid buying electricity when wholesale prices spiked.

“Solar plus storage,” as it is known, is gaining traction in the power industry, but Maine’s investor-owned utilities are not moving in that direction. Neither one actively promotes time-of-use (TOU) pricing either, a simpler measure that gives customers an incentive to use electricity outside peak periods, lowering their own rates and reducing the overall demand that can drive costly system upgrades.

For Emera Maine, TOU pricing is “not a large consideration going forward,” says its media communications specialist Judy Long.

“CMP does … offer TOU rates for customers who seek them,” Catharine Hartnett, the utility’s corporate communications manager, wrote in a recent email. But she acknowledged that the PUC had ordered CMP to update those rates in 2014, and the company only submitted its revised rates to the PUC last October.

A Not So Smart System

CMP used customers’ desire for greater control over electricity pricing to justify its installation of smart meters eight years ago, a $196 million investment (roughly half of which ratepayers covered, with the balance coming from federal stimulus funds). CMP also promised that the meters would improve outage responses.

Yet during a major windstorm in October 2017, nearly half a million CMP customers were left without power for days when much of the system crashed. “We were blind in a way we hadn’t been in a very long time,” CMP spokesperson John Carroll told the media at that time.

“People were sold a bill of goods (with automatic metering),” says Dick Rogers, business manager for IBEW Local 1837, the union representing 1,600 electrical workers at CMP and Emera Maine. “Meter readers were the company’s eyes and ears” in the field, and provided backup support during storms. Now, he says, CMP uses “an incredible number of contractors who don’t know the system like we do.”

The erosion of CMP’s workforce began in the mid-2000s with an exodus of experienced line workers following early-retirement offers. The union estimates the number of district service personnel – line workers, field planners and clerical staff in smaller regional offices – fell 15 percent between 2006 and 2018 (not counting the loss of meter readers when the company converted to automatic metering).

The staff cuts occurred just as more challenging weather patterns associated with climate change began to manifest; “we’ve definitely seen stronger and more frequent storms,” Emera Maine’s Long says.

Maine now has the dubious distinction of ranking first among states in both the average number of power interruptions and the average number of hours interrupted (42 hours, compared to 15 in Vermont and a national average of 7.8).

Those outages represent a significant loss for Maine businesses. In a column for Forbes, William Pentland, a vice president at the energy consulting firm Genbright LLC, estimated that even a 10 percent reduction in the length of CMP’s annual outages could reduce the economic impacts for customers by more than $100 million annually.

Beyond worst-in-nation reliability and smart-meter challenges, CMP has lost public trust through persistent billing problems, poor customer service, a customer data breach and a contentious transmission line proposal that aggrieved ratepayers with service complaints consider — in the words of one Jackman resident – “salt in the wound.”

A different option

The PUC (with encouragement from the Public Advocate’s Office) should be ratepayers’ first line of defense in getting affordable and reliable service, and it did recently threaten enforcement action against CMP for a host of infractions.

However, the PUC’s culture and decision-making process are not particularly accessible to the public.

More fundamentally, says Littell, the former Maine PUC commissioner, “the last administration politicized public servants simply doing good work for the public, and drummed talented and dedicated career civil servants out of state government.” In some cases, this has blurred the lines between regulators and the entities they are supposed to scrutinize.

Several PUC decisions in recent years — such as a report that CMP responded “reasonably” to the October 2017 windstorm — have raised questions about whether the commission is favoring industry over public interest. The relationship with industry now appears so close that CMP CEO Doug Herling recently published an op-ed defending the PUC against a critical editorial.

Vermont’s B Corp utility, while an intriguing model, could not be implemented in Maine’s investor-owned utilities without the support of the multinational corporations that control them. GMP also has rates comparable to Maine’s and – as is typical of investor-owned utilities – generously rewards shareholders and executives, with its CEO earning a salary of $576,000 in 2017.

A bill now before the Maine Legislature proposes a dramatic departure from the broken status quo: creation of a “Maine Power Delivery Authority” that would buy the assets of CMP and Emera Maine and contract for transmission and distribution of electric services with an entity required to hire those companies’ workers. This independent authority would represent a fundamental shift in ownership (from investors to electricity consumers), in structure (from private to nonprofit) and in mission (from maximizing shareholder returns to meeting ratepayers’ needs).

The bill’s sponsor, Berry, co-chair of the state’s Energy, Utilities and Technology Committee, says he wants to make Maine’s primary transmission and distribution utilities “responsible to our priorities.”

He also wants to ensure that rates are affordable and that Maine provides opportunities like on-bill financing to give lower-income ratepayers greater access to energy efficiency and solar power. Berry calculates that financing the purchase of utility assets with low-interest revenue bonds (not taxpayer-funded bonds) could reduce electric rates by 10 percent to 15 percent.

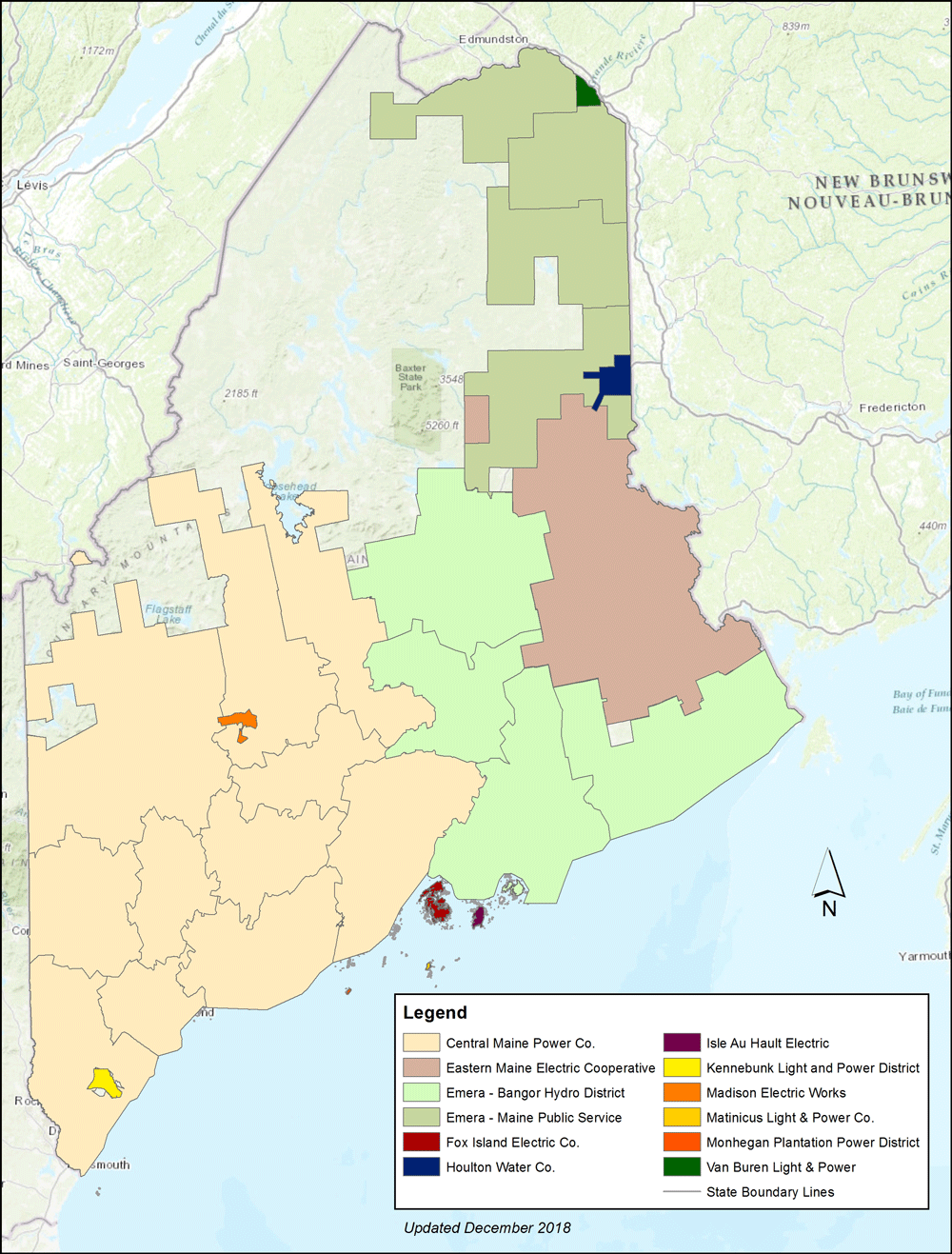

Maine already has nine publicly owned utilities operating on a smaller scale, a mix of municipal power districts and cooperatives that — excluding anomalous island utilities — typically have lower rates than CMP and Emera Maine.

The last administration politicized public servants simply doing good work for the public, and drummed talented and dedicated career civil servants out of state government.”

— David Littell, former commissioner at the Maine Public Utilities Commission

Public ownership of utilities allows for greater participation and increased accountability, Berry notes, with meetings open to the public and all records subject to Maine’s Freedom of Access legislation — conditions that don’t currently apply to investor-owned utilities.

The proposed consumer-owned utility would be akin to the Maine Turnpike Authority in structure, being overseen by a nonpartisan independent board and not reliant on taxpayer dollars. That analogy might concern those who recall that the MTA’s former executive director pleaded guilty to felony charges and served jail time for charging several hundred thousand dollars in unauthorized expenses.

“But it’s easier to hold entities accountable when they’re local,” Berry says, pointing out that investigative work by the Legislature’s Office of Program Evaluation and Government Accountability helped uncover that graft.

Establishing a public utility typically involves a feasibility study, a legal analysis, potentially a public referendum and finally an agreement on price, explains Ursula Schryver, vice president of education and customer programs at American Public Power Association. Over the last nine years, Boulder, Colorado has been inching closer to creating a municipal utility. In the process, it has pushed its current investor-owned utility (Xcel Energy) to commit to going 100 percent carbon-free by 2050.

Dozens of U.S. communities each year begin exploring public power ownership, Schryver reports, but only 68 have formed new utilities since 1980; “it’s a difficult process,” she adds, typically with “a lot of legal battles and communications campaigns.”

Littell concurs with her assessment, adding that it’s a “David and Goliath fight; there are not equal resources there.”

Maine ratepayers might even end up footing the tab for the utilities’ legal battle. When asked about that prospect, Harry Lanphear, the PUC’s administrative director, acknowledges “the answer is not a straightforward one. We would evaluate legal costs (in the context of their impact on ratepayers) as part of a formal proceeding, and make a determination as to what we would allow or not allow. It would be adjudicated, with lawyers weighing in on both sides.”

Public power supplies roughly one in seven American electricity customers, but Nebraska is the only state where it serves everyone (about 1.9 million people total). Rather than having a singular power authority as Maine is envisioning, it has 166 smaller entities.

In 2018, U.S. News ranked Nebraska first among states for “power grid reliability,” 17th for electricity prices, and fourth overall. Maine’s rankings in those categories were 40, 49 and 42.

Nebraska’s conversion to public power dates to the 1930s, when Republican Sen. George Norris sought reform following a period of excess utility greed and corruption. As Weil wrote in his book “Blackout: How the Electric Industry Exploits America,” Norris “came to believe that investor-owned utilities could never operate in the customer’s interests … (he) simply removed the profit motive from the utility business.”

Maine already took a step in that direction in forcing a major restructuring of the regional power industry in the late 1990s, when six New England states restricted utilities to T&D, opening energy supply to free-market forces. “Generation costs went down; competition worked,” Weil says.

Maine considered a switch to public power as early as 1973, he notes, and 38 percent of voters favored the measure even though delivery costs then represented 20 percent of consumers’ bills. Today, they have risen to 50 percent, he says; “generation-side savings were absorbed by increased transmission costs.”

A time for discussion

Berry put forward his power proposal because after 10 years of service in the Legislature, he says he’s “convinced Maine needs to reconsider the structure of our utilities.” Rogers of the IBEW concurs that the idea “deserves to be vetted to see if this works better for the people of Maine.”

The prospect of creating a consumer-owned utility may shift Maine ratepayers from a reactive stance – filing complaints with the PUC and logging social media gripes – to collective brainstorming on what might best serve consumers here. Many other states already have begun fostering constructive dialogue on grid modernization issues, with working groups tackling topics like electric vehicle charging and sharing of aggregate energy-use data.

When discussions involve a potential shift to public power, Schryver notes, there are often “concessions and incentives” made by utilities to better meet local needs. That’s been the case in Minnesota, where a statewide initiative launched in 2014 has gotten parties talking informally outside the typical regulatory context, discussions that are yielding concrete benefits for ratepayers.

As conversations in Maine move forward, it’s increasingly clear here – and across the nation – that “a whole cultural shift” (in Littell’s words) may already be underway.