Maddox Williams’ short life began with a struggle to survive.

The blond-haired boy was born in January 2018 and weighed just under three pounds. From his start as a premature infant through his toddler years, Maddox bounced between parents who battled drug and alcohol addictions, mental health illnesses and their own childhood traumas.

Six months before his fourth birthday, Maddox died of blows so severe they fractured his spine and caused bleeding in his abdomen and brain. His 35-year-old mother has been charged with his murder.

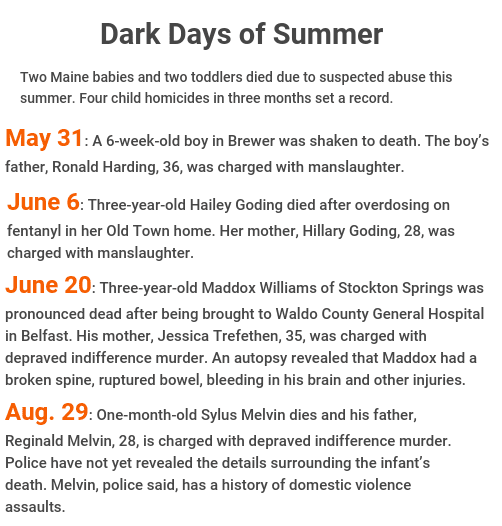

Maddox was the third Maine child to die of suspected abuse between May 31 and Aug. 29. Four child homicides were recorded during that three-month period, a record high. From 2015 through 2020, according to Maine’s Vital Records, a total of six children were murdered.

The recent deaths renewed concerns about the state’s child welfare system, and prompted investigations by Maine government agencies and a national child advocacy group. Maddox’s story, child advocates say, is a tragic reminder of the precarious and unstable families that many Maine children are born into. Child neglect, abuse or deaths often involve parents struggling with poverty, substance use disorders, and the fallout from their own troubled childhoods, said Mark Moran, who chairs Maine’s Child Death and Serious Injury Review Panel.

“These are families that often function day to day at a minimally accepted level,” said Moran. “They are families that often are in a crisis of one sort or another. A stressor that an average family, who doesn’t have these kinds of limitations and could move beyond with relative ease, knocks these families way off kilter.”

Typically, Moran said, several months or even years before the death of a child, the state’s child protective caseworkers have been called to the home for other concerns.

“In so many of these cases there have been several previous (Department of Health and Human Services) reports listed,” Moran said. “The reports go back many years, often times before the birth of the deceased child.”

• • • •

Jessica Johnson grew up in Stockton Springs, a small coastal community of 1,600 that borders Belfast and Bucksport.

In her teenage years and 20s, family members say, Johnson grew dependent on drugs.

“I reached out to her,” said Laurie Johnson, who married and later divorced Jessica Johnson’s uncle. “I tried helping her.”

Johnson, who lives in Searsport and works as a cook for the Belfast school department, said at one time she was close to her ex-niece.

“I told her to get the hell off the drugs,” said Johnson. “My son tried to talk to her, too.”

Johnson said her ex-niece’s first child was a girl.

“Her oldest daughter didn’t want anything to do with Jessica,” Johnson said. “She’s 13 or 14 now and living with her dad.”

As Jessica birthed three more children with Jason Trefethen, who also lived in Stockton Springs, Johnson saw less of her ex-niece.

“I’d run into her every now and again at the store in Searsport, and that’s about it,” Johnson said.

Years later, Jessica Johnson met Andrew Williams, who was living in Belfast at the time, his mother Victoria Vose said.

Williams also battled substance use issues and suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder after watching his dad shoot himself, Vose said.

“I’ve spent many years,” Vose said, “trying to keep my son alive. He has suffered post-traumatic stress since he was 18 and watched his father kill himself.”

Andrew Williams’ relationship with Johnson was complicated by their emotional and mental health struggles, and the children they had with other partners. Williams had a young daughter.

Despite their differences, Johnson married Williams and the two had a “volatile relationship,” Vose said.

In 2017, she became pregnant with Williams’ child and the baby was expected in late March 2018. In December 2017, Jessica began having complications with her pregnancy.

“She was in the hospital and doctors told her she needed to stay in there or she’d have the baby prematurely,” Vose said.

Jessica left the hospital, Vose said, and two weeks later, on Jan. 9, gave birth to a blond-haired boy she named Maddox.

“He was 11 weeks early and weighed less than three pounds,” said Vose.

Nurses placed Maddox Williams in an incubator to keep him warm. Pads on his tiny chest monitored his heart and oxygen levels. Though they were separated, Maddox’s mother and father spent time at the hospital with their son.

After nearly two months of specialized care, Maddox was released to his mother, Vose said.

“I begged the social worker not to let her leave the hospital with him,” said Vose. “I was worried about Maddox.”

Vose knew Maine DHHS’ Office of Child and Family Services had been involved with some of Jessica Williams’ other four children.

“The history went back several years,” Vose said.

Swaddled in a hospital blanket, 2-month-old Maddox went with his mother to live in a trailer with her previous partner, Jason Trefethen, and the couple’s other three children. Within weeks, police were called to the home.

The Waldo County Sheriff’s Office received a 911 call on March 22, 2018, at 2:05 p.m. reporting that a child had overdosed on methadone.

Stockton Springs Police Officer Michael Larrivee raced to the trailer at 30 Cross Lane. When he arrived, Larrivee found Trefethen on the phone talking to the 911 dispatcher.

“Jason was panicking trying to get help,” Larrivee said. The overdose victim was Trefethen’s 2-year-old son.

“I got there the same time the ambulance did,” said Larrivee. “I ran in and the kid was on the ground. I picked him up and ran out to the ambulance. He was conscious and alert.”

As the ambulance took the boy to a hospital, Larrivee contacted DHHS to report the incident. It was unclear whose methadone was involved.

“They didn’t say whose methadone it was,” Larrivee said. “I guess it was in a pill bottle and the kid grabbed it. I don’t know how much he took. There was nothing criminal, so it was all left to DHHS.”

DHHS removed all of the children from the home, including Maddox, who was now 2½ months old. Child protective workers contacted his Maddox’s father, Andrew Williams.

“They notified my son about the overdose and asked him to come get Maddox,” said Vose.

At the time, Williams and his young daughter were living with Vose. “When DHHS called, we had nothing (for him) and had to go get everything for this little newborn,” Vose said.

Over the next two years, Vose doted on her grandson. Jessica and Andrew Williams divorced and Jessica began using the last name Trefethen. She only saw Maddox once over the next 24 months, Vose said, due to the restrictions on her visits.

“My son didn’t want her to bring the father of her other children to the supervised visits,” Vose said. “So she only saw Maddox one time after his doctor’s appointment. I didn’t understand. If I was the mother, I would do everything possible to see my child.”

As Maddox grew stronger and gained weight, Vose said her son relished spending time with him. Vose posted pictures on her Facebook page of Williams holding and kissing Maddox in the hospital when he was a few weeks old. Another picture posted in September 2018 shows a smiling Williams holding Maddox in his lap as they sat on a swing.

“My son loved his children and would never intentionally harm his kids,” Vose said.

Williams also continued to struggle with post-traumatic stress disorder.

“My son was doing great here when he was living with me,” said Vose, “but at some point something happened, and then he wasn’t doing so well when he got on his own.”

On Jan. 28, 2020, Williams was caught burglarizing a Rockland apartment. Police reports say the man who was living in the apartment heard a child cry and when he went downstairs, found Williams holding a small child in one arm, and a box of speakers and other items in his other.

Williams, the officer noted, was under the influence of drugs at the time. Concerned about Maddox, the officer called DHHS to the scene to take care of the 2-year-old boy who was not appropriately dressed for the cold.

RELATED STORY: What more can be done? Some are haunted as child deaths in Maine continue to rise

A fateful reunion

Two weeks later, on Feb. 12, Vose said DHHS and a judge agreed that Maddox should be returned to his mother.

“They handed him over to a stranger that he hadn’t seen but once in two years,” Vose said.

Over the next several months, Vose and her son, who was out on bail for charges related to the January burglary, tried to see Maddox.

“Jessica didn’t let us see him for several months,” Vose said. “My son was supposed to get him every other Friday. I was constantly worried about Maddox when she had him.”

Williams, Vose said, contacted the Waldo County Sheriff’s Office and asked them to do well-being checks on Maddox. He eventually hired an attorney and was able to get his son for visits again, Vose said.

“The judge said (Jessica) would go to jail,” Vose recalled, “if she didn’t allow us to get him.”

The visits with Maddox ended when Williams was arrested on March 7. Police reports say he was intoxicated while driving with Maddox and another child in the car. Released on bail, Williams was arrested again in Warren on March 18, and charged with illegal hunting and possession of a firearm by a prohibited person.

In March, during the last time he saw Maddox, Williams noticed his son had bruises on his back and a cut over his eye, Vose said. He photographed the injuries to make sure he wasn’t blamed for them.

When Williams asked his ex-wife about the marks, she said her 4-year-old son had thrown a toy at his younger sibling.

After Williams’ March arrest, Trefethen refused to let Vose see her grandson. “I’d call Jessica and ask to see him,” Vose said, “and she’d always say she was too busy.”

On Thursday, April 8, at 1:25 pm, the Stockton Springs Police Department responded to a domestic violence report at the trailer where Jessica and Jason Trefethen lived with their three children, and Maddox Williams.

According to officer Jonathan Shaw, Jason Trefethen was arrested for assaulting Jessica.

“All four kids were there,” said Shaw. “It was less than favorable conditions. And I felt in my professional opinion that I needed to call DHHS immediately after the criminal aspect was resolved to make a referral.”

After the incident, Jason Trefethen was placed under a court order not to have contact with Jessica, Shaw said.

Over the next month, Vose continued to call Jessica Trefethen requesting to see her grandson. Sometimes she talked to Maddox on the phone. She asked how he was doing with his potty training and promised to buy him some pullup training underwear.

The last conversation Vose had with Trefethen occurred in June.

“She told me, ‘We’re going camping for two weeks and you can see him when I get back,’ ” Vose said.

Weeks later, on Sunday, June 20, Trefethen and her mother, Sherry Johnson, brought Maddox to the Waldo County General Hospital in Belfast, according to a police affidavit. Maddox was not breathing and had no pulse when he arrived. Doctors were unable to resuscitate him.

Trefethen told hospital emergency room staff the boy had been knocked down by a dog leash and kicked by his 8-year-old sister.

An autopsy later performed by Maine Deputy Chief Medical Examiner Dr. Lisa Funte showed that Maddox suffered severe injuries, including a fractured spine, and bruises on his arms, legs, head and abdomen.

Partially healed abrasions were found on Maddox’s face and forehead, which were covered with temporary stick-on tattoos. Funte also reported deep tissue bruising on his buttocks, and internal bleeding in his abdomen and brain. The injuries, Funte noted, were not consistent with a fall or being knocked down.

Victoria Vose learned of her grandson’s death after her daughter heard that Maddox had died.

“I had to get hold of the state police and find out what happened,” Vose said. “Then my son called me, and I thought he knew. I just lost it and said is it true? Did it really happen?”

Williams, who was in the Knox County Jail at the time, asked his mother, “What are you talking about?”

“I had to tell him what I heard,” Vose said. “He had no clue. He is the father and he should have been notified immediately.”

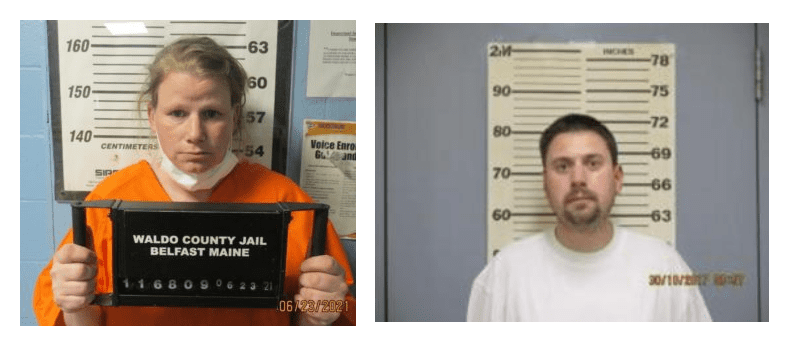

Charged with depraved indifference murder, Jessica Trefethen is being held at the Waldo County Jail. Her next court date is scheduled in October. Vose and Trefethen’s family members say she is pregnant and expecting her sixth child. Her other three young children are now 8, 4 and 2 years old. It is unclear where they were placed after Maddox died.

If convicted, Trefethen faces life in prison. Trefethen’s attorney, Jeffrey Toothaker, did not return two phone calls requesting an interview.

Two weeks after his son’s death, Maddox’s father was convicted of several charges related to burglarizing a Rockland home and driving under the influence. He was sentenced to 18 months in prison. A judge denied Williams’ request to be released to attend his son’s funeral.

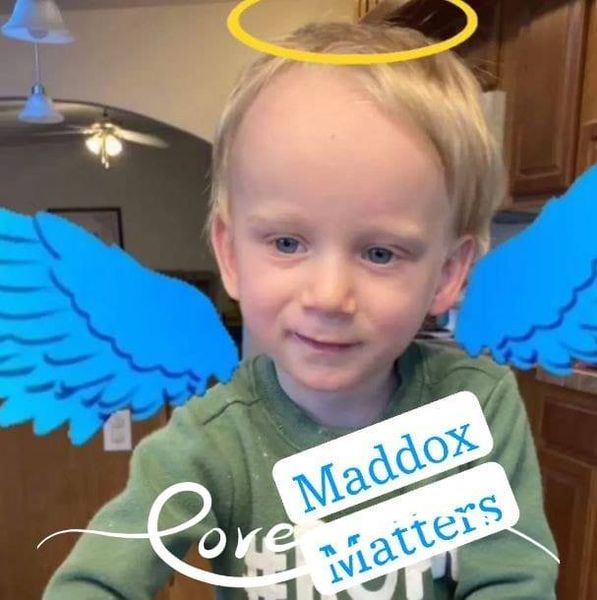

Vose and other family members held a private service for Maddox. After his burial, a bouquet of yellow and white flowers was placed over Maddox’s grave. An orange stuffed Elmo doll sat in a toy tractor on the edge of the bouquet. A plaque with a picture of Maddow rested in the middle of the memorial. It read “In loving memory of Maddox A. Williams January 9, 2018 – June 29, 2021.”

Vose often visits her grandson’s grave in the cemetery near her home in Warren. Sometimes Maddox’s older sister accompanies her and they bring a bottle of bubbles, so they can blow tiny water balloons over his grave.

“He was my little helper,” Vose said. “He loved to help me cook and clean.”

Vose has had difficulty sleeping since her grandson’s death. She thinks about his struggle as a premature baby, his short turbulent life and his horrendous death.

“He was only 20 pounds,” Vose said. “He was tiny. I can’t comprehend that someone could hurt him like this, break his spine.”

Vose does not understand why no one spoke up for the boy with a shy smile.

“His death could have been prevented if somebody could have just spoken up,” Vose said. “He was a sweet, good boy. And now the only thing I can think about are the horrific injuries and the pain he suffered.”

A GoFundMe page has been set up to help cover Maddox’s funeral expenses, to “get justice for those responsible for his death,” and to provide a scholarship fund for a Maine student pursuing a degree in social work.

Maine’s child abuse hotline is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week. If you suspect child abuse or neglect, call 800-452-1999. Calls may be made anonymously. Click here for more information on the reporting process.