Last summer, a former deputy clerk and treasurer of the town of Newburgh was sent to jail after pleading guilty to taking the town’s money, nearly $200,000 of it.

Last spring, the Pleasant Point police chief pled guilty to taking $33,000 from the Passamaquoddy tribe.

Last year, the former Frenchboro treasurer pled guilty to a $5,250 theft; the former Amity town manager pled no contest to the charge of theft of $40,000; and a former Rumford parks and recreation superintendent pled guilty to theft for selling a piece of town equipment and pocketing the $1,500 proceeds.

A Maine Center for Public Interest Reporting examination has found that over the past five years at least $800,000 has been taken from municipal coffers across Maine in the form of money or services by local officials whose job was to faithfully and honestly serve their towns. And this has often come at steep cost to the towns, not just in missing money but in added fees and charges, not to mention hard feelings.

The extra charges — sometimes thousands of dollars — go to cover attorney fees and the cost of additional forensic audits that are used to substantiate what are often complicated cases of theft. According to a Kennebec Journal report, legal fees for a Chelsea case involving irregularities in municipal contracting could total more than $300,000, for example.

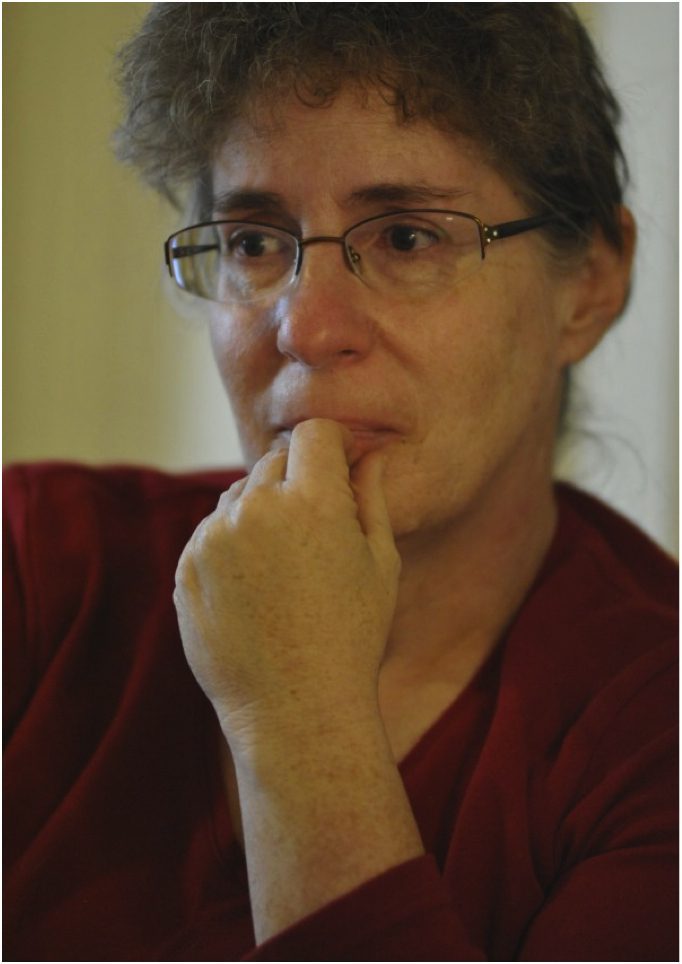

Like many cases involving fraud, the crime of the Newburgh official, Cindy Dunton, went on for several years, from 2006 to 2009. It was uncovered beginning in March 2010 after two Newburgh selectmen noticed discrepancies in the town annual report between their figures and Dunton’s.

‘Stole our trust’

A certified fraud examiner who was called in to investigate alleged, in an audit reported by the Bangor Daily News, that Dunton had stolen from the town in a range of ways, including forging select board members’ names on town checks. The money went toward paying her health insurance premiums and property taxes, as well as a number of other purchases, including drill bits. The grand total of missing money, according to the report: $199,536.54. Dunton acknowledged her guilt.

Newburgh, a town of slightly more than 1,500 in Penobscot County, reacted strongly: Residents gathered names on a petition calling for the longest jail sentence possible.

On July 1, Dunton was sentenced to five years with all but 20 months suspended. She also received three years of probation and was ordered to pay approximately $252,000 in restitution— the sum of money that she stole, plus attorney and forensic auditor fees. Enraged citizens had demanded a 10-year sentence.

As one irate Newburgh selectman, Mike Burns, said, “She didn’t only steal our hard-earned money, she stole our trust and the innocence of the town of Newburgh. Newburgh isn’t a happy place to live any longer.”

Representing the concerned citizens, called The Fixers, Chris Yount presented the petition signed by about 200 residents. According to the BDN, he asked the judge, “Please do not dilute the justice that the people of Newburgh so richly deserve.”

In Chelsea, scene of one of the most recent cases, former member of the select board Carole Swan has pleaded not guilty to felony charges of aggravated forgery (for falsifying a public record) and attempted theft (alleging that she authorized a $22,075 check from the town to pay for a fraudulent invoice). She is also charged with two counts of improper compensation for services, alleging that she received money for promoting contracts while she served on the board. She declined to run for reelection last June.

The charges revolve around Swan’s alleged acceptance of kickbacks from a snowplow contractor, as well as allegations that she oversaw favorable treatment of her husband’s construction company, which has done work for the town. A trial date has not yet been set.

The uproar surrounding Swan’s case was accompanied by the termination last June of the Chelsea town clerk, Flavia “Cookie” Kelley. An investigation by Kennebec Journal reporter Mechele Cooper found that, despite no municipal experience, Kelley had received compensation that exceeded that for clerks in every other Kennebec County town the size of Chelsea. Kelley has since filed suit against the town.

Voters at a special town meeting in March set aside $50,000 to cover legal expenses and the cost of an audit. The final legal fees could total nearly $320,000, according to the newspaper.

Hundreds of municipal officials are serving their towns and cities without incident, but crime statistics indicate that embezzlement and other kinds of theft from government, along with corporate theft, have increased notably in the state and across the country over the past decade. And this crime, with its added costs, comes at a time when Maine’s towns and cities are dealing with shrinking budgets. In a survey conducted by the Maine Municipal Association, municipalities recently reported a six percent drop in operating revenue last year, compared with 2009.

BECOMING MORE COMMON

Historians note that in past centuries Maine, like the rest of the U.S., was soaked in a partisan political atmosphere that saw all kinds of chicanery among town officials. Bribery and theft regularly occurred until the 20th century, when new forces of reform overtook local government, particularly in cities, which began hiring managers to keep municipal business in order. Today, though, despite the professionalization of many city and town officials, corruption remains a smaller but stubborn problem.

“When I started out, the idea of selectmen or a town manager stealing money was rare, but over the last 10 or 12 years it has become more common, unfortunately,” said Christopher Almy, district attorney for Penobscot County, where Newburgh is located.

Almy added that the full picture couldn’t necessarily be found in the stories that make their way into local newspapers and websites. His office also considers — and rejects — cases in which there may be cause for some investigation but ultimately not enough evidence to bring charges. He declined to say how many of those cases had crossed his desk in recent years.

Statistics, both state and national, seem to bear out his perception of a general increase in fraud. Nationally, the total of government and private embezzlement cases increased nearly 17 percent in 2010 compared with the preceding year, according to a detailed report issued by Marquet International Ltd., a business-consulting firm based in Boston. The report noted that of the 13 sectors or industries it listed as primary victims, government agencies and municipalities had the most cases, accounting for $48.2 million in losses.

As of last June, the FBI was working on more than 2,000 corruption cases involving public officials around the country, and in 2009, the latest year for which statistics are available, U.S. attorneys across the country charged 270 local officials with corruption and won 257 convictions (148 officials were awaiting trial).

Maine has kept a low profile, compared with other states: five Maine officials were convicted of corruption in federal courts in 2009.

Numbers posted annually by the state Department of Public Safety show that arrests for embezzlement—both public and private—in Maine totaled 20 in 2002, but shot up to 56 in 2007, and have cooled to 43 as of 2010.

MMA: NOT A TREND

Eric Conrad, spokesman for the MMA, said, “We want to emphasize that we’ve seen no data indicating an upward trend in municipal embezzlement cases. These things happen rarely. When they do, they tend to be reported to police and they get widespread publicity, which can last for years. That’s eye catching but it’s not necessarily a trend.”

While Almy has perceived an increase in fraud cases in Penobscot County, Evert Fowle, DA for Kennebec County, said simply that to him “it’s been a fairly constant problem.”

The cases present a challenge to his office, he said, because they are labor-intensive and the special audits involved are expensive for the towns.

Experts say that a lack of deep training in financial record-keeping and uneven oversight by town officials have contributed to this problem. The thefts primarily occurred in the smaller towns among the nearly 500 Maine municipalities, where there may be few people available to furnish the second pair of eyes that theoretically should see every town transaction. Among the cases of theft that have come to light during the past five years, the towns that were victimized had an average population under 3,000.

Mike Starn, city manager of Hallowell and former communications director for the Maine Municipal Association (MMA), said that in many cases there are “similar diagrams of the problem. The person who takes funds has usually been in the community for a long time, they have been given ‘extreme latitude’ in taking care of town finances, and local financial practices among town officials — such as routine oversight of town finances — are very lax.”

Too many town finance people are “learning on the job,” said Ron H. R. Smith, managing partner of RHR Smith and Company, certified public accountants with offices in Buxton and Machias, whose firm handles about 140 annual municipal audits. He added that, despite the increasing sophistication of computerized accounting, “quite a few people in smaller municipalities don’t have technical expertise.”

The last decade also brought new challenges to municipalities with the introduction in 1999 of accounting standards that made greater demands on town money managers. Saco became the first municipality in Maine to adopt the new accounting standards (in 2001), which chiefly require that municipalities inventory, value and depreciate all their assets.

SOLUTION: PROFESSIONALS

This placed a big burden on many small towns that had worked more or less independently to deal with their routine accounting needs. According to an article in Maine Townsman, the magazine of the MMA, Maine is unique in New England in allowing towns to run their own financial affairs with certain requirements set by the state. Maine demands that all town and city finances undergo an annual audit and publishes a list of allowable municipal investment options, but otherwise keeps out of municipal finance. By contrast, Massachusetts and New Hampshire oversee their municipalities to the point that the states actually set municipal tax rates. Vermont has no municipal finance law beyond requiring its towns to follow the “prudent investment rule.”

Some in Maine, including Professor Tom Taylor, head of the University of Maine’s department of public administration, have called for a professionalization of all town government—the hiring of town or city managers to work on finances and other local matters under the scrutiny of a council or select board.

“You need more than one person to sign off on financial matters,” he said. “Having a town manager brings more transparency and accountability.”

He agrees that many small towns cannot afford to hire managers, but he says the problem could be addressed through mergers of town functions, if not the towns themselves. Many towns, he notes, are already cooperating on joint purchases from snowplowing services to office supplies to sharing the services of a single assessor.

At a workshop at MMA’s annual convention in October, representatives of several towns said their governments were involved in joint sewage, solid waste disposal, ambulance districts and billing services.

But until full mergers put professional administrators in charge, small towns will rely on training classes, online instruction, reviews and coaching that are offered every year, primarily by the MMA. State administrators (from the state auditor’s office, for example), as well as at least one individual accounting firm have also been working hard to improve local officials’ competence in handling their own municipal finances.

The meeting room deep within the Augusta Civic Center was packed Oct. 5 as town and city finance officials found seats for one of the many popular workshops at MMA’s annual two-day convention. The sessions ranged from “Not Your Father’s Health Care System” to the one that filled the center’s first-floor Kennebec Room with a standing-room-only crowd: “Understanding Your Audit.”

The workshop’s first topic: fraud and its detection.

‘People we trust’

Speaker John S. Eldridge III, Brunswick’s finance director, said, “I can’t speak to individual situations, but a lot of things happen when you trust people. Fraud is committed by people we trust.”

And, he added, the annual audit “shouldn’t be the only means for looking at fraud.”

He added, “The purpose of an audit is to render an opinion on whether the financials have been fairly stated.”

In other words, an audit won’t necessarily find problems if someone has made an effort to hide them.

An audit is only as good as the financial statements presented to the auditor, according to accountant Ron Smith, who in addition to running his own firm serves as a certified fraud examiner.

In a later interview, Smith emphasized that the major problem that can lead to fraud, or simply problems in keeping a town’s accounts, is the fact that “a lot of people are learning on the job—they’re part of the problem. Add to that the many places that are trying to do so much with so little money. That can be a recipe for disaster,” he said.

Starn acknowledged that the training has its shortcomings: not everyone takes advantage of it. But for now there is no easy solution.

“Look, the state can’t create one model for municipal government,” said Starn. “For now, we have to fix the model that towns have.”

Theft cases fuel suspicions and towns see more demands for data

The high visibility of embezzlement cases in some Maine towns has made residents in many cities and towns more skeptical, even suspicious, of what goes on in their towns.

Officials are seeing those feelings show up in a dramatic increase in residents’ requests – sometimes demanding and on short notice – to know how their tax dollars are being spent.

The Maine Municipal Association (MMA) has reported that as many as 20 communities have struggled to keep up with waves of citizen requests made under the state’s Freedom of Access Act, according to the Bangor Daily News.

MMA spokesman Eric Conrad noted in the article that the current load of requests has stressed and distracted town officials who are already busy. And the suspicion that has accompanied some demands has affected morale in town offices.

The MMA has expressed its dismay at a proposed bill that could change state law to make requests for information even easier to make, by allowing people to make these requests by telephone and by requiring town workers to provide an immediate response. The bill would also provide money for a part-time public information ombudsman in the attorney general’s office. The proposal was held over from the last legislative session to allow more study.

The growing call for information has, however, resulted in pushing more towns toward better and wider use of the internet. Towns are now scanning more paper documents to make them accessible online.

Online use has also grown at the state level, where at least a couple of agencies have not only made reports and other information available on their websites, they have established hotlines so that persons with knowledge of illegal acts can report them.

In the state auditor’s office, reports of possible criminal acts by officials can be made in confidence, while the state Department of Health and Human Services takes reports of fraud primarily about those who receive benefits.

In both cases, the reports must be about misuse of state funds, not local budgets. Reports received by both agencies must be accompanied by detailed information and cannot be made anonymously.

The auditor’s fraud hotline, launched in 2008, has seen a steady growth in the number of complaints lodged. In its first six months, it saw five complaints; in 2009, there were 24; last year, a total of 29, and in the first six months of 2011 there were 20.

“This department investigates state government, not municipalities,” said state auditor Neria Douglass, acknowledging that, while she has the authority to look at any town or city’s books, she does not have an investigative unit. She said she refers information received on her website to other, more appropriate agencies—other state agencies, or district attorneys’ offices—for follow-up. Her small office staff does not have anyone designated to receive complaints by telephone.

She said she was pleased with the response to the hotline, although it is still something of a work in progress. Some citizens still see it as a place to make personal complaints against local officials.

Where the money was lost

Here are examples of lost money and property in Maine municipalities in cases that have come to light during the past five years:

Willimantic, 2007: Former Treasurer and Tax Collector Jacqueline Gorey admits embezzling $46,000 from the town over a 10-year period.

Waterford, January 2009: Former Deputy Town Clerk Jennifer Morin sentenced after pleading guilty to embezzling $158,000 from town of Waterford between 2002 and 2008. The county sheriff’s office said that most of the money was used to pay for bounced-check fees and credit cards bills, as well as gifts.

Bucksport, March 2009: Former Deputy Town Clerk Darla Crawford pleads guilty to theft of nearly $37,000 from town office between 2002 and 2006.

Wiscasset, November 2009: Former clerk Sandy Johnson pleads nolo contendere in the case of $90,000 found missing from the town’s accounts.

Ludlow, February 2009: Former town manager Mary Beth Foley suspended without pay and the town office is closed while the state investigates the town’s financial records. She resigns in July, after the state auditor discovers $3,000 in discrepancies in town finances.

Amity, May 2010: Former Town Manager Darrell Williams pleads no contest to a charge of theft of $40,000 during the five years he was in office until his resignation in 2007.

Frenchboro, September 2010: Former Frenchboro Treasurer Dan Blaszczuk pleads guilty to theft of $5,250 20 years after he vanished with the town’s checkbook. The money was part of a total of $10,000 discovered missing from town while he was in office. He was found after a local emergency dispatcher’s search of the Internet.

Rumford, March 2011: Former Parks and Recreation Superintendent Timothy J. Gallant pleads guilty to theft for selling a piece of town equipment in 2007 and pocketing the $1,500 proceeds.

Pleasant Point, April 2001: Former Police Chief Joseph Barnes pleads guilty to stealing $33,000 from the Passamaquoddy tribe in 2007 and 2008 to feed a gambling habit.

Newburgh, April 2011: Former Deputy Clerk Cindy Dunton pleads guilty to embezzling nearly $200,000 from the town.

Chelsea, August 2011: Former Chelsea select board member Carole Swan pleads not guilty to charges including forgery, attempted theft and improper compensation for services.

To report fraud, abuse, or other improper or illegal acts to the state auditor use the online complaint form or send e-mail to vog.e1752915670niam@1752915670tidua1752915670.duar1752915670f1752915670 or write to: Maine State Auditor, 66 State House Station, Augusta, ME 04333-0066.