As Burcu Sagiroglu listened to lawmakers debate a bill that would establish a statewide tracking system for sexual assault kits, her mind wandered back to her days as a student at Colby College.

She remembers numerous friends confiding in her that they had been sexually assaulted on campus, yet many of them did not feel comfortable reporting the assault to authorities. At the time, she didn’t understand why.

“After six years in this field I’m like, okay. I completely understand now,” said Sagiroglu, who is a policy and advocacy associate at the Joyful Heart Foundation. “A lot of survivors are just left in darkness.”

Maine does not have a statewide tracking system for sexual assault kits, which are used to collect DNA and other evidence in the immediate aftermath of a sexual assault. This means survivors often need to make calls to their local hospital or police department to find out where their kit is located and when the testing will be complete, a process that advocates said can be daunting and amplify feelings of powerlessness.

“You have more ability to track your Amazon packages or anything right now than you do to be able to find a kit that contains personal, sensitive information about a crime against someone’s body,” said Arian Clements, the executive director of the Sexual Assault Support Services of Midcoast Maine.

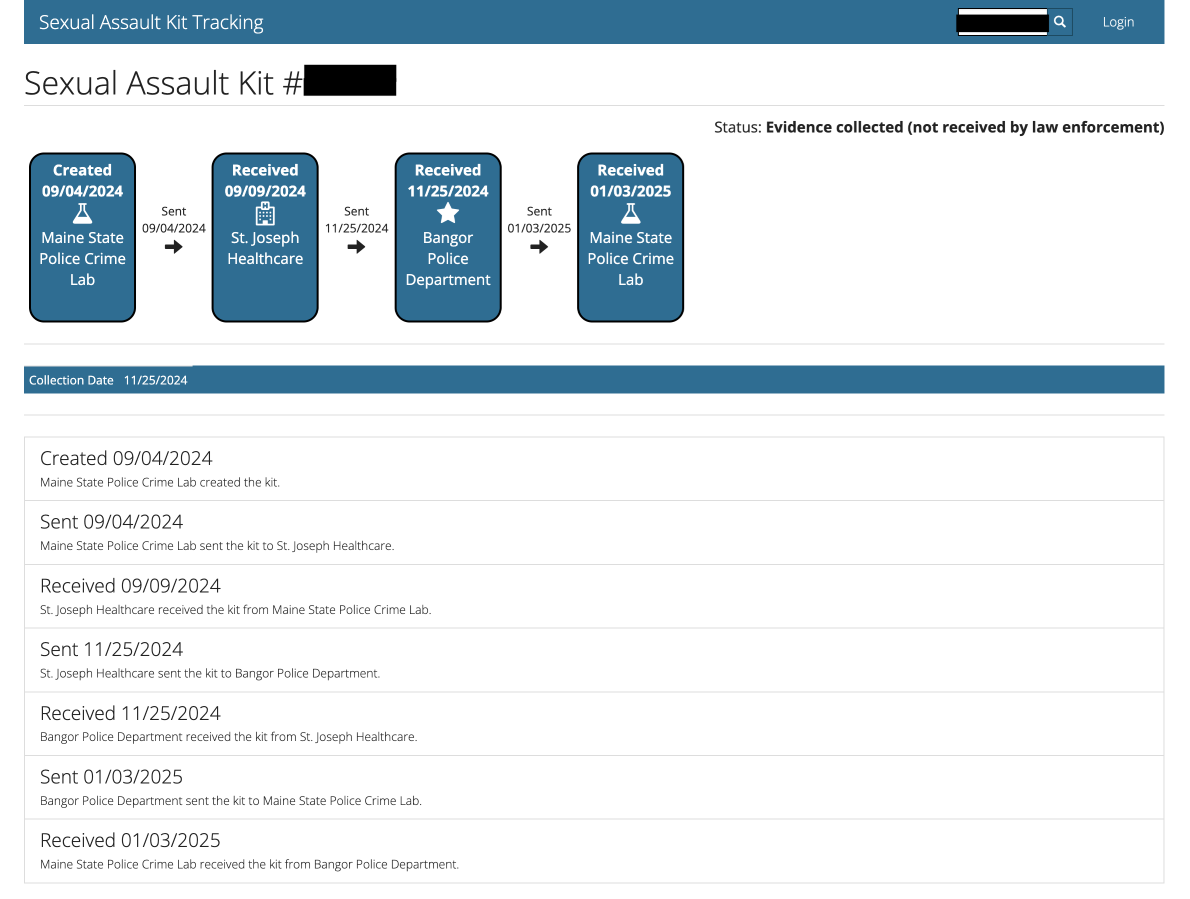

A bill before the legislature, L.D. 549, would change this process. It proposes a standardized tracking system that would allow victims to see the status of their kits online.

“When tested, the DNA evidence from rape kits can be a powerful tool to solve and prevent crimes. DNA evidence can identify unknown assailants, link crimes together, and exonerate the wrongfully convicted,” Sagiroglu wrote in her testimony. “Too often, however, these rape kits languish untested for years — even decades — in storage facilities.”

Nationally, 34 states and Washington D.C. have adopted a statewide tracking system, according to End the Backlog, an initiative of the Joyful Heart Foundation that advocates for better state and federal transparency and accountability for sexual assault survivors.

The bill would give Maine nearly two years to produce a report on the inventory of kits in the state, and would make it mandatory to send all kits, even those not associated with a crime report, to the Maine State Police Crime Laboratory beginning in January 2027.

Advocates say it’s important to mandate the testing of all kits, not just those associated with criminal cases. But given concerns about capacity at the state crime lab, lawmakers amended the bill’s requirements for testing backlogged kits to focus on those being investigated as part of a crime.

Undergoing a sexual assault examination is up to the victim, as is the decision of whether to report the assault to law enforcement. Law enforcement agencies are required to store rape kits for 20 years.

A version of the bill was sent to the governor’s desk last year but was not signed into law.

There are roughly a quarter million untested rape kits at police stations and hospitals across the United States, according to the Joyful Heart Foundation.

“When somebody is murdered with a knife, for instance, we know that that knife has important DNA evidence, and it will get tested for sure,” Sagiroglu said. “So why don’t we test rape kits that also have DNA that is equally important to the criminal justice process?”

The organization recommends several key reforms for states to adopt: the creation of statewide tracking systems, testing existing inventory and backlogged kits, mandatory testing for all newly created kits, and an online portal that allows survivors to track the status of their kits 24/7.

Efforts to establish a tracking system and address the backlog are already underway through several federally funded initiatives in Maine.

In Cumberland County, the district attorney’s office received a three-year, $2.5 million federal grant to address the backlog of kits. The money, which was announced in December, will be used to send about 500 sexual assault kits out of state for testing.

The Maine Coalition Against Sexual Assault received $90,000 in 2023 for a pilot project to track sexual assault kits in Kennebec and Penobscot counties.

The pilot project has successfully established a tracking system for new kits and has counted the inventory of kits at most hospitals in the counties, but has yet to inventory kits held at local law enforcement agencies.

Carlie Fischer, the systems advocacy coordinator for MECASA, said she hopes the bill will help the state expand this work to other communities. Though the $90,000 has run out, her organization has funded her continued work on the project.

She said it’s important that survivors feel supported throughout the entire process.

“It’s important that when they do make those reports that they feel heard, believed, listened to, taken seriously,” Fischer said.

To reach a sexual assault advocate, call the free and confidential support hotline at 800-871-7741.