When a threatening letter arrived at her Portland apartment building earlier this month, Charlotte Stanton found out via text message from her neighbor.

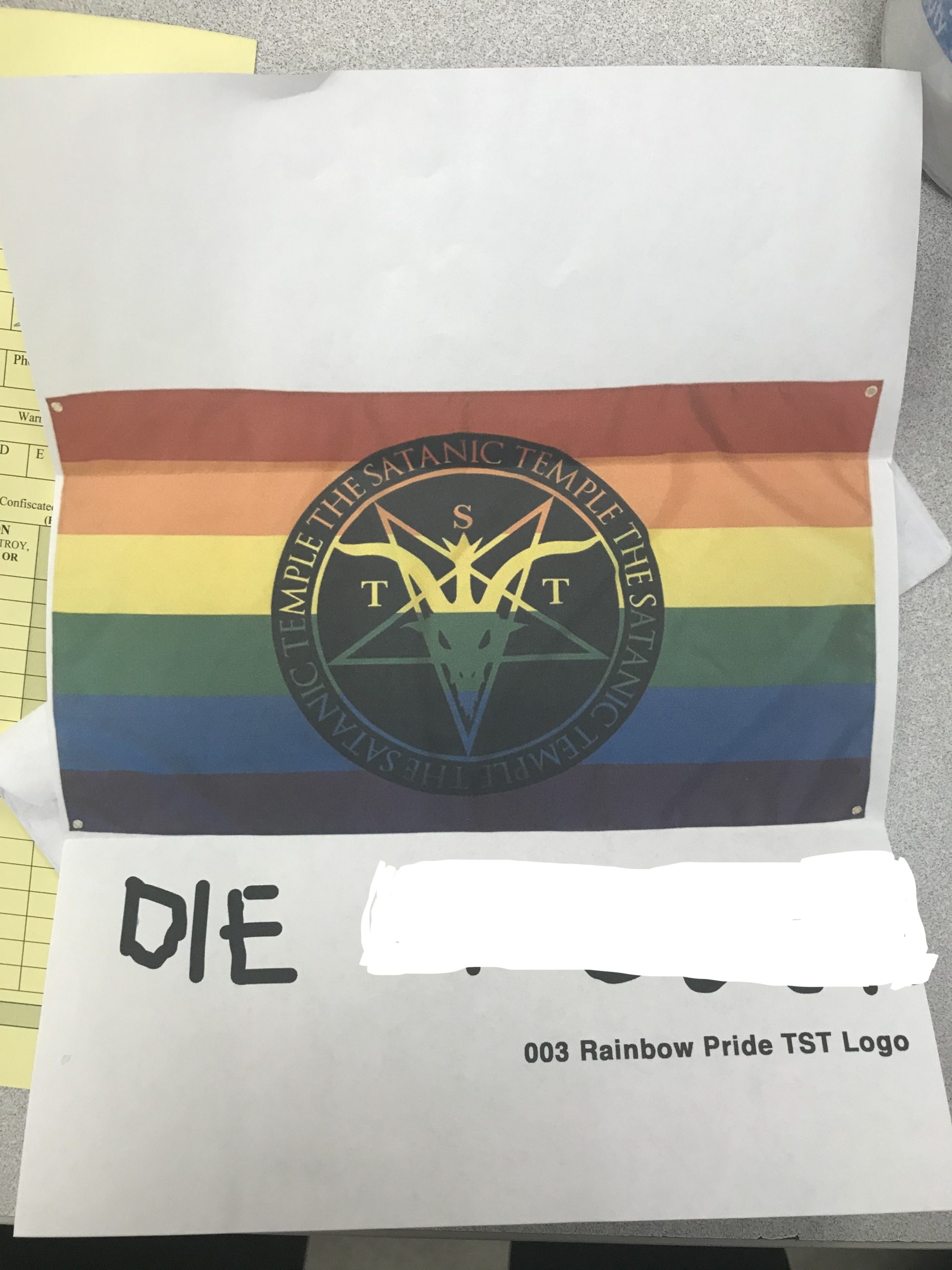

The neighbor opened the envelope, addressed to “residents.” It contained an image featuring a pride flag with the Satanic Temple logo superimposed on top. The word “die” was followed by a homophobic slur. Because Stanton and her partner, Abigail Geringer, display a pride flag in their window, they knew they were the intended recipients.

“I just feel angry,” said Stanton, 30. “We’re in the middle of a pandemic, huge political upheaval. As a white lesbian, I feel safe most of the time. It made me feel really furious. It felt unfair to make me feel unsafe.”

This month, eight residents of Portland and South Portland have received the same homophobic death threat in the mail, said Lt. Robert Martin, spokesman for the Portland Police Department.

“It’s very serious,” Martin said. “Somebody knew their address, had driven by to see a pride flag or Black Lives Matter sign. It took effort. They computer-generated a letter, wrote out the address, put a stamp on it and mailed it.”

Martin said while most people who received the letters displayed a pride flag, some had other signs that expressed support for Black Lives Matter, science and gay rights.

And going back to October, three more anonymous letters police believe were sent by the same person invited people to a meeting at an address on Capisic Street to discuss social and political issues, he said. But the people who lived there had not called a meeting and had no idea someone was using their address to invite people for a discussion and snacks, according to Martin.

Martin said they suspect the letters are being sent by one person, not an organized group.

“There’s some intent,” Martin said. “Do they take it to the next level? Do they break a window?”

For LGBTQ Mainers, threatened violence or vandalism is not new, said Portland City Councilor Andrew Zarro, owner of Little Woodfords, a coffee shop on Congress Street. Last February, a customer lashed out at Zarro, who is gay, after being asked to leave for causing a disturbance.

“Within 10 minutes he was threatening my life, saying the most hateful things,” Zarro said, adding that the threats included homophobic slurs. “It’s terrifying.”

A few months ago, the rainbow flag he flies outside his coffee shop “was ripped down and urinated on,” he said.

“This is not an uncommon thing to carry around in your subconscious,” he said. “There’s always a chance of somebody doing or saying something to you. It’s a sad reality.”

This is not an uncommon thing to carry around in your subconscious. There’s always a chance of somebody doing or saying something to you. It’s a sad reality.”

— Andrew Zarro, Portland city councilor

Just 30 miles northwest in Standish, Tim Goodwin spent six months in 2020 contending with a group of people who repeatedly defaced and destroyed his wooden sign painted with the colors of the pride flag. He also endured hateful speech.

“One person who saw me and a female friend standing the sign back up yelled ‘straight lives matter’ and ‘all of you fags get out of my town’ at us,” he said. “Someone placed a sign that read ‘homosexuality is an abomination to our God’ next to the pride sign.”

Other signs expressing support for the Black Lives Matter movement or Goodwin’s belief in science were stolen. When the ground froze and snow fell, he removed his signs from Standish Center, but they will be back in the spring.

“The vandalism is proof there is a sentiment in the community where LGBTQ people are not welcome,” he said. “It’s important to continue the message that (Standish) is inclusive and welcoming of this community. If we stop putting the signs up as a result of being bullied, it sends the wrong message.”

The recent death threats and harassment of gay and lesbian Mainers, and their allies who openly support them, come at a time of national turmoil and division. Stanton doesn’t think it’s a coincidence that someone who makes the effort to send death threats to LGBTQ people chose this time to make their feelings known.

“I think it’s part of a larger political movement,” she said. “As we see things with the Capitol insurrection and the inauguration, it’s part of a bigger statement.”

Matt Moonen, executive director of EqualityMaine — the state’s largest LGBTQ advocacy organization — agreed. He described the death-threat letters as “disconcerting,” particularly in light of the recent upheaval at the Capitol and around the country.

On Jan. 6, an armed mob of insurrectionists breached security at the U.S. Capitol, killing one police officer and leading to the deaths of four others following a speech by former President Donald Trump, who he continued to lie about winning the presidential election.

“I don’t think those are mutually exclusive,” Moonen said. “There are folks in this country who feel empowered by violence and hate.”

Nationally, hate crimes in the U.S. rose to their highest level in more than a decade in 2019, the most recent year with data available, according to an Associated Press story in November based on an annual FBI report that tracks hate crimes. There were 7,314 hate crimes in 2019, up from 7,120 the year prior, the wire service reported. More alarmingly, the highest number of hate-motivated killings since the early 1990s was reported in 2019, with 51 hate-crime murders.

In Maine, from 2010-19, there were 119 reports of incidents related to bias against people because of their sexual orientation, according to the FBI database. That’s 32 percent of the total incidents reported, which included bias related to race, religion and disability.

During that 10-year period, the highest number of reports of bias related to sexual orientation came in 2011, when there were 26. But in more recent years, there have been just a handful – four in 2017, six in 2018 and seven in 2019.

And when it comes to civil rights orders issued by the Maine Office of the Attorney General in cases involving bias against someone because of their sexual orientation, there were 12 from 2010-18. That’s nearly 11 percent of the bias cases reported to the FBI during the same period.

There are folks in this country who feel empowered by violence and hate.”

— Matt Moonen, executive director of EqualityMaine

For comparison, there were 156 cases of race-related bias reported in the same time frame and 23 civil rights orders issued. That equates to about 15 percent of the race-related cases reported to the FBI.

Marc Malon, a spokesman for the state attorney general, noted that its office must be able to show violence, threats of violence or property damage based on bias against the victim to support a civil rights enforcement action.

Civil rights orders are issued after a local police department reports an incident to the attorney general’s office and the office deems there is sufficient evidence to prove a civil rights violation, said Leanne Robbin, an assistant attorney general. The restraining order prohibits the defendant from going near the victim; if it’s an act of property damage, they are not allowed near that area again. If they violate the order, the AG’s office can bring a criminal charge, she said.

Many times, local district attorneys pursue criminal charges at the same time the AG’s office puts in place a civil rights order, she said. Defendants also can be disciplined by district attorneys even if no civil rights order is in place.

When same-sex marriage was approved in 2012, Maine became one of only three states in which voters — rather than legislators or courts — extended the right to gays and lesbians. And that vote came three years before gay marriage was legalized nationally with a Supreme Court ruling.

Voters have not always supported gay marriage in Maine. In 2009, citizens overturned the state’s first same-sex marriage bill, which had been approved by the Legislature and signed by Gov. John Baldacci.

‘Trauma to someone’s doorstep’

It appears the threatening letters have been sent only to residents of Portland and South Portland. Spokespeople for the Maine State Police, Biddeford, Bangor and Lewiston police departments all said they had no reports of those types of letters.

City councils in Portland and South Portland put out strongly-worded statements condemning the death threats. In Portland, residents were encouraged to fly the pride flag to show support.

“The South Portland City Council joins in solidarity and support with our LGBTQIA+ friends and neighbors who have received such letters and wish to unite in rejecting hatred and bigotry in our community, as well as in our nation,” reads a resolution dated Jan. 12.

Zarro, who is serving his first city council term in Portland, said he felt it was important for city officials to quickly condemn the letters. Since urging residents and businesses to fly the pride flag, Zarro said he’s been overwhelmed to see how many flags are now flying in the city. He said he and others are ready to do the hard work of trying to heal the divisiveness.

“People are ready on both sides of the aisle,” he said. “People are ready to stop ripping each other apart.”

Zarro said he sympathizes with those who received the letters.

“These people or person are targeting people at their home,” he said. “You are bringing trauma to someone’s doorstep.”

Martin said it’s been difficult to get clean fingerprints or DNA off the envelopes because the letters were opened by the recipients and sometimes handled by police officers. And even if they could get clean fingerprints or DNA, the person would have to be in a police database to find a match, he said.

Martin said police ask that if anyone receives a suspicious letter to not open it and call police immediately. Another strategy for police is to try to track down where the paper was purchased by identifying fibers, colors or watermarks that might help them understand if it’s unique to a particular store.

In a press release issued Jan. 6, Martin said “there is no indication that the Satanic Temple or its members are responsible for this mailing.”

The Satanic Temple, which charges itself with promoting social justice, actually defends gay rights. More than half of its national members identify as LGBTQ, the group’s founder said in 2019.

Martin described the death threats as “amateurish,” one reason police believe it is likely one person, not a group, behind them. Also, there are spelling errors indicating the person is not highly educated — or at least has an outdated version of Word that does not have spell check. Regardless, he advises that anyone who receives a letter to be cautious, but not to the point of changing how they live.

“If these letters were hand-delivered I would be more concerned,” he said. “They are using the Postal Service so they don’t want contact.”

Noting that he hopes the anger in the country has “calmed down a little bit,” since President Joe Biden took office, Moonen of EqualityMaine said the community — from council members in Portland and South Portland to those flying pride flags — have shown they won’t tolerate these types of hateful acts.

“We do think local law enforcement and the AG’s office should be investigating this,” he said. “As far as I can tell, they seem to be taking this seriously.”

Stanton sees the death-threat letters, and national political and social upheaval as opportunities to encourage everyone to look out for one another. She appreciates the number of pride flags flying in Portland and hopes supporters can take it one step further by calling their LGBTQ friends to check in and make sure they are OK.

“This is happening to people you know,” she said. “We have to look out for each other.”