In the past year and month, record-breaking weather extremes in line with the expected impacts of a warming world have brought disruption, destruction and even death to all corners of Maine.

It feels like something has shifted — more than ever, Maine people have been forced to confront the consequences of climate change not as a future hypothetical, but as a present reality.

“It’s overwhelming,” said Hannah Pingree, the co-chair of the Maine Climate Council, in an interview with The Maine Monitor. “The last month has made us all feel like, ‘Oh, wow, these climate impacts are really here. I didn’t think these things would happen so soon.’”

The state Climate Council and Gov. Janet Mills will hold a special public meeting next Tuesday to take stock of recent events and look to the future, including their next four-year climate plan due at the end of this year. The meeting, just announced, will be the first time the council has convened on short notice after a disaster, or a slew of them. (Register to attend virtually or in person.)

Earlier this week, Mills wrote to President Biden to request a federal disaster declaration for the Dec. 18, 2023 storm that brought torrents of river flooding and massive power outages. She also asked the Federal Emergency Management Agency to begin assessing the same designation for the tidal flooding and storm surge that swept away entire coastal structures last weekend.

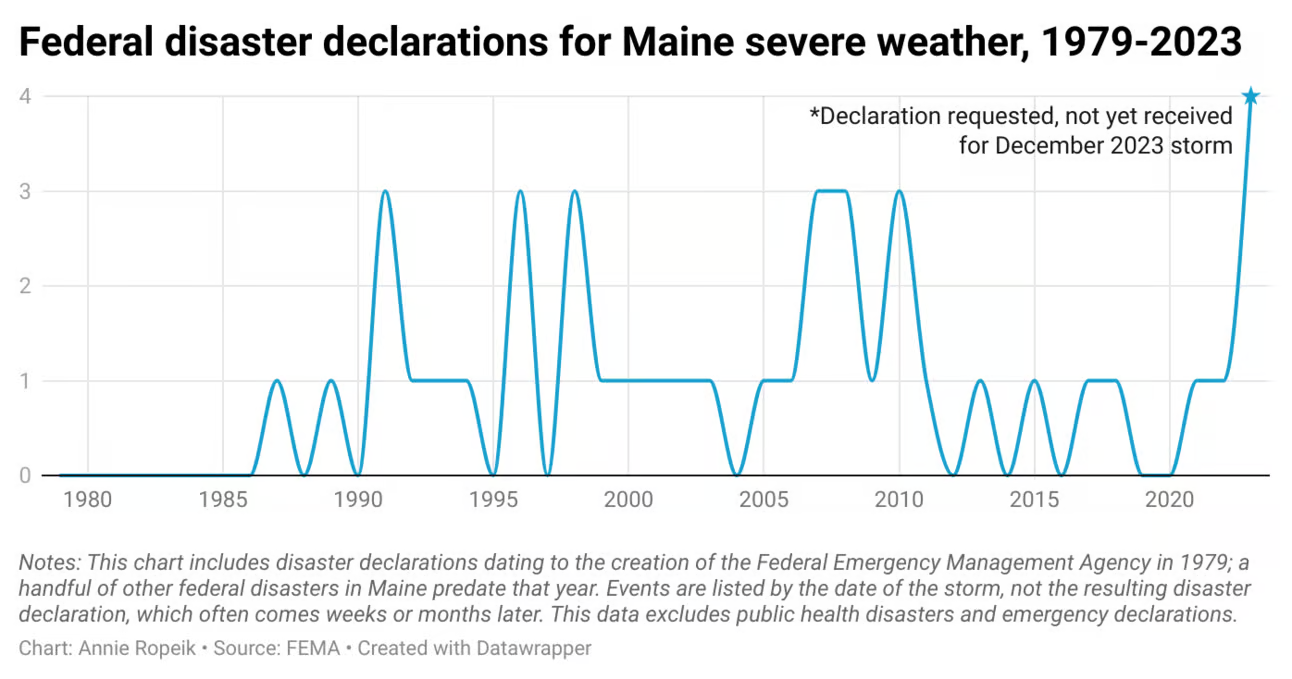

If these requests come through, it would make six declared weather disasters in Maine since December 2022, and four in 2023 alone.

FEMA data shows Maine has seen three of these at most in any past year. It’s just one striking metric of the worsening new normal Maine is now living through.

“All the scientists tell us that this kind of change was coming,” Pingree said, “and now we can see it with our own eyes.”

No one weather event can be directly linked to climate change without careful modeling, an evolving science known as climate attribution. But heavier rain, higher tides and other such impacts should come as no surprise.

“Human activities have unequivocally caused the global warming observed over the industrial era, altering the intensity, frequency, and duration of many weather and climate extremes, including extreme heat, extreme precipitation and flooding, drought, and wildfire,” the latest National Climate Assessment said.

As these extremes become more common, so do disasters, which “occur when hazards meet vulnerability,” a group of researchers wrote in an academic journal commentary in 2022.

“We must acknowledge the human-made components of both vulnerability and hazard and emphasize human agency in order to proactively reduce disaster impacts,” they said.

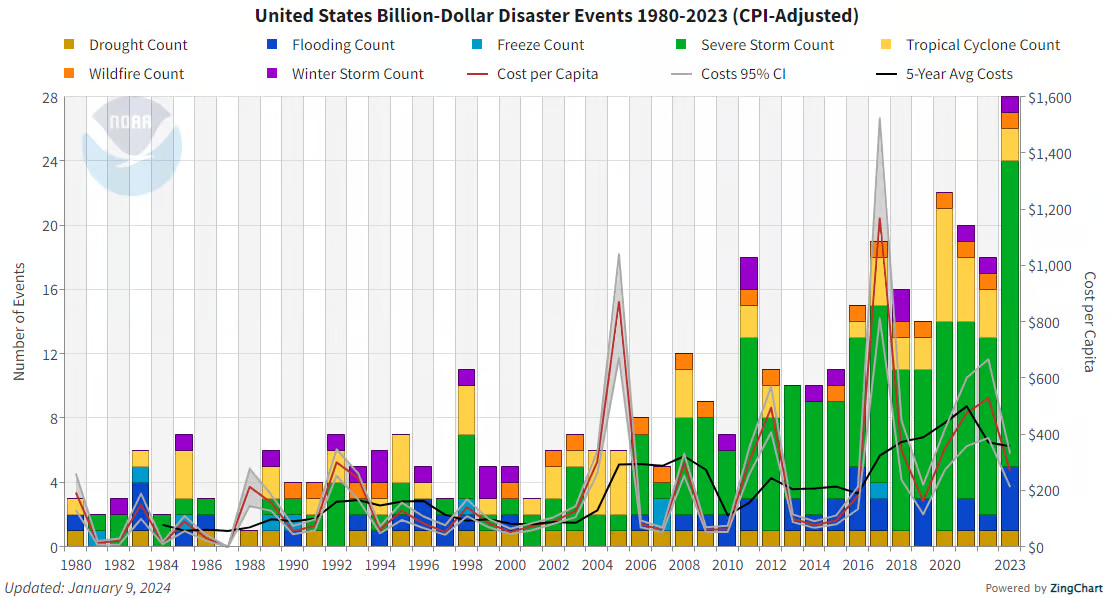

In 2023, the U.S. saw a record 28 weather disasters that cost more than a billion dollars, reports the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

“The number and cost of weather and climate disasters is rising due to a combination of population growth and development along with the influence of human-caused climate change on some type of extreme events,” NOAA said in a Jan. 8 blog post.

This vulnerability is not just physical, but socioeconomic, with people of color and low-income communities disproportionately affected.

NOAA noted that 2023’s disaster costs “may rise by several billion when we’ve fully accounted for the costs of the December 16-18 East Coast storm and flooding event that impacted states from Florida to Maine.”

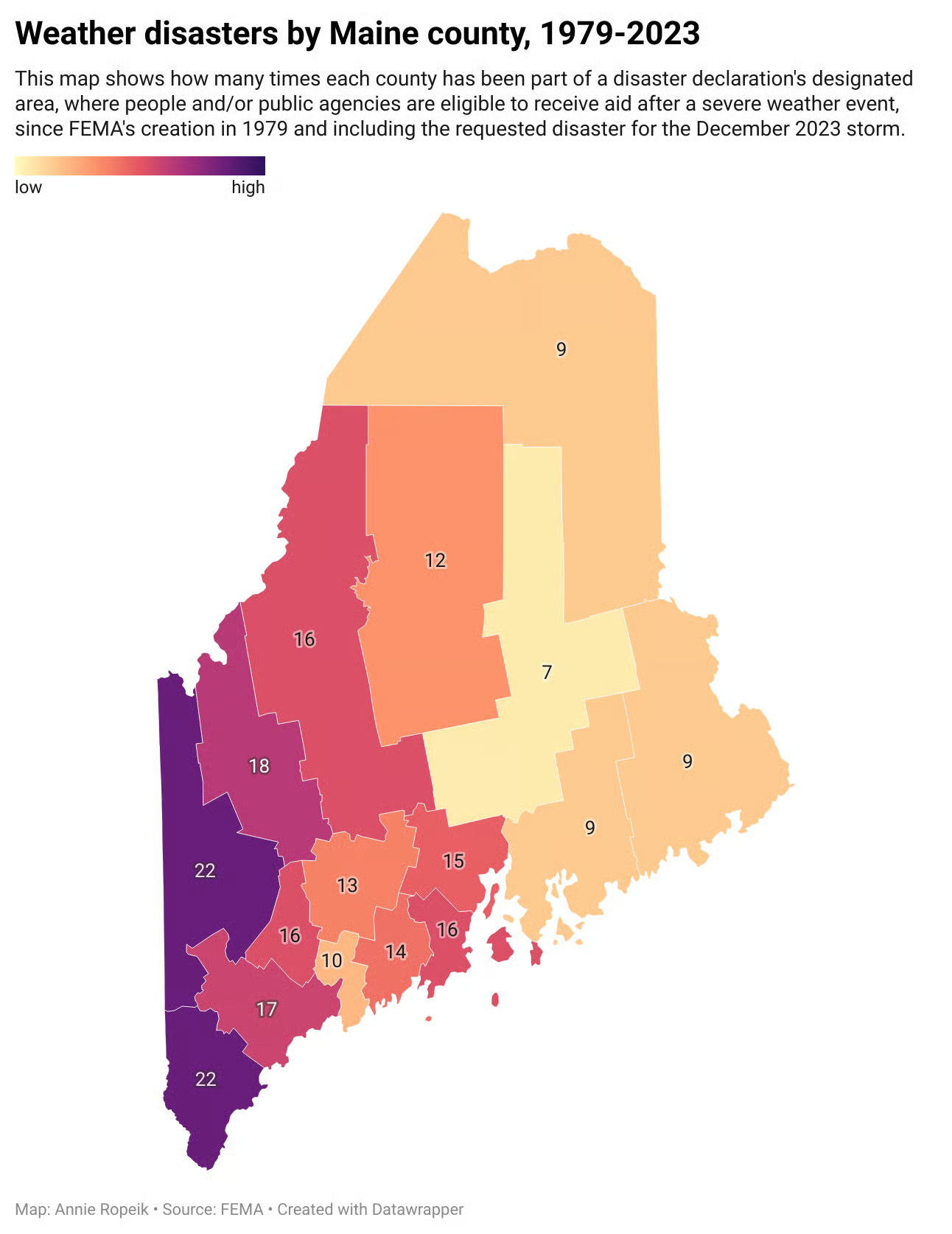

For its part, Maine has received an average of $5.8 million a year in federal disaster aid since 2000, according to FEMA data. This money most often goes to government agencies and eligible nonprofits to rebuild affected infrastructure.

If property damages are great enough, the state may also seek individual aid to help people rebuild their homes and lives. Mills requested this aid for people in five counties affected by the December storm.

Other storms that have led to this kind of funding have included Hurricane Bob in 1991, the 1998 Ice Storm and the high-cost 2007 Patriots’ Day Storm. But Maine doesn’t get individual aid often — the last time was in 2008.

Anne Fuchs of the Maine Emergency Management Agency said the funding requires a lot of uninsured damage to structural elements or living spaces in houses. “In Maine, where we have a lot of basements, it is harder to meet the criteria,” she said.

Mills, in her letter to Biden, said the December storm’s worst damage affected a heavily low-income population that is already having trouble recovering. And the increased frequency and intensity of storms has left “all levels of government” struggling to “respond and recover,” especially in Western Maine, she said.

It’s a heavy, anxious moment, staring down a future of ever-worsening extremes from an already destabilized position.

Yet the actions we take now will help ease the harms that future holds. Any amount of emissions we cut back on today will save us a little more warming in the future. Rebuilding from one storm in a way that better prepares us for the next one will save money and lives.

“We need everybody to be understanding their vulnerabilities and taking action,” Pingree said. “The challenge is that … we are still in a time period where the level of sea level rise, the change in weather patterns, is going to be determined by our ability to reduce emissions. It’s a lot for people to manage, because we’re trying to figure out how to rebuild at the same time.”

All Mainers can do is keep working on both fronts, she said — individually and with communities around the U.S. and world, adding up to vital progress.

“It’s hard, but it still is incredibly important that we keep our eye on both making the state of Maine more resilient (and) doing our part to reduce emissions,” Pingree said. “They’re both equally important.”