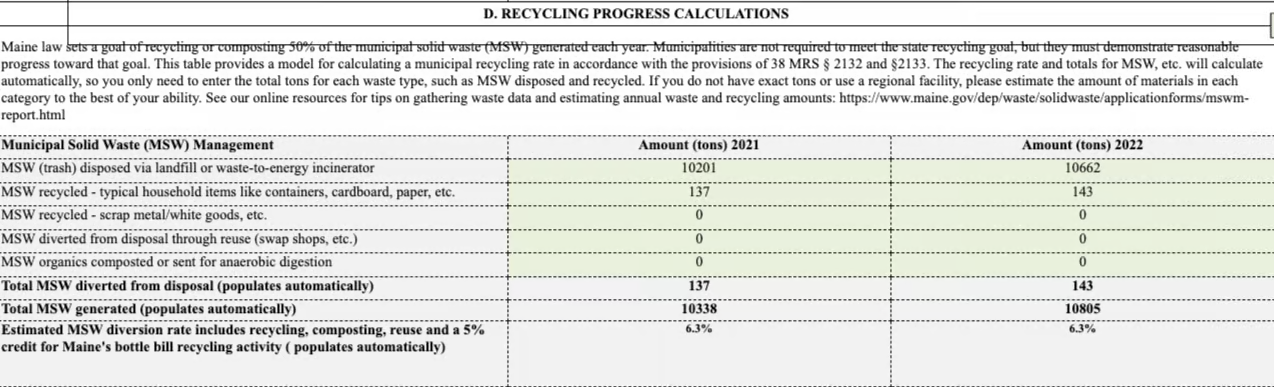

Three years ago, I spent several days reading through 145 municipal recycling reports. Towns and cities across Maine are required to report to the Department of Environmental Protection every two years on their solid waste management and recycling practices.

The records are intended to help determine whether communities are making “reasonable progress” toward Maine’s goal of recycling or composting 50 percent of our solid waste (we’ve yet to come close).

My hope had been to create a database with recycling rates by town, but I quickly abandoned the idea. The documents, which covered the years 2019 and 2020, were PDF files. Most had been filled out by hand, meaning any kind of large-scale data analysis would have required deciphering handwriting and manually inputting the information into a spreadsheet.

Of those that had been filled out, many had blank pages. Some municipalities said they couldn’t get a breakdown of waste disposal and recycling from their transfer stations, which might collect waste from several towns.

Others claimed recycling rates of more than 100 percent, or said they had recycling rates greater than zero while reporting “0” for the tonnage of waste recycled or composted. Some of the rate calculations appeared incorrect. It was a data analyst’s nightmare.

The story we eventually ran focused mostly on the lack of data. That year, the DEP received fewer than 150 reports from Maine communities out of the nearly 500 that were notified, a response rate of around 30 percent. That was up from the previous round, when the state got 107 replies.

Compliance this time around has been better. Between April 2023 (when responses were due) and last week, DEP received around 340 reports, said Courtney Hafner, an environmental specialist with the department.

Staff mailed written reminders and made more than 800 phone calls and emails to communities whose reports were late, said Hafner, adding that “147 municipalities never returned our emails/phone calls.” Many were more than a year overdue.

In an effort to streamline data collection, the state introduced a new fillable spreadsheet for municipalities. The majority of responses came in this way, although Hafner noted that some communities filled out the old forms regardless and mailed them in.

The data from this batch is also clearer. Recycling rates were calculated automatically, reducing the number of calculation mistakes. There’s no handwriting to parse. But it’s still spotty, with many reports missing answers.

As for the actual rate of recycling and diversion of waste from landfills, it’s fairly dismal. Communities around Portland, home to ecomaine, one of the state’s largest recyclers, are diverting anywhere from a third to half of their waste from landfills. A few coastal towns and even some island communities also reported relatively high rates, from 27 percent in Stonington to 52 percent in Vinalhaven.

In much of the state, however, almost all of the waste is being landfilled. Bangor recycled just 6 percent of its municipal solid waste last year. Lewiston reported rates of 18 percent; in the far north, Limestone was at 13 percent. A number of towns said they no longer had recycling programs at all.

If you’ve been following recycling in Maine, these numbers won’t surprise you. As The Monitor reported in January, between 2018 and 2022, the amount of municipal solid waste landfilled in Maine shot up 47 percent, from 388,629 tons in 2018 to 569,911 tons in 2022.

“I’ll just come right out and say it: It’s easier to throw away trash than it is to recycle it,” Susanne Miller, director of the Bureau of Remediation and Waste Management at the Maine DEP, told lawmakers at a briefing earlier this year.

Maine is taking steps to change this. Earlier this month, after several years of development, the citizen board that oversees DEP finalized rules intended to reduce the amount of packaging waste produced in the state, a program known as extended producer responsibility for packaging, or EPR. Maine already has a number of EPR programs that have been in place for years, including for paint, mercury thermostats, batteries and unused drugs.

An important goal of this new program, which DEP staff expect to implement within the next two years, is also to collect better data and to help offset the cost of recycling. To get reimbursed, communities will have to report recycling and diversion figures annually, and will be required to participate in cost studies and audits of their recycling stream.

The big question, of course, is how many municipalities will participate. In the most recent recycling survey, communities were asked whether they were interested.

The answers were mixed. Larger towns mostly supported the idea (with the exception of South Portland, whose director of public works said “no” even though town officials have advocated for the plan in the past). Many smaller communities were interested but said they needed more information, or worried about the additional costs.

“It will depend how much additional work is required to manage the program,” wrote Erik Street, director of public works in Yarmouth. “Limited resources and staffing make it difficult to take additional programs on.”

Many left the answer blank.