Editor’s Note: The following story first appeared in The Maine Monitor’s free environmental newsletter, Climate Monitor, that is delivered to inboxes for free every Friday morning. Sign up for the free newsletter to get more important environmental news from reporter Kate Cough by registering here.

My husband and I are expecting our first child in September. Adding a whole person, even a very small one, to a household means acquiring a lot of things: diapers, of course, but also creams and bags and wipes and onesies and bouncers and various devices of increasing complexity for carting a small person around.

Much of this gear has come second hand, but a lot of it has also been (very generously) gifted by family and friends, arriving at our house in a steady parade of bags and boxes, which has made the last month feel a bit like a really long and wonderfully drawn out birthday. The anticipation is heightened by the fact that the bags and boxes arriving on our doorstep are themselves often filled with more bags and more boxes, and, in some cases, more bags and boxes still, held in place by airy plastic pillows. The Russian nesting dolls of packaging.

This week, while sorting the recycling and attempting to decode which of the various aspects of the packaging could potentially go on to have another life, I virtually “attended” two programs: one, from College of the Atlantic, titled “Turning the Tide on Plastics,” and the other, put on by the Product Stewardship Institute, called (slightly less sexily) “The Latest on 2022 EPR Legislation.”

The lectures were interesting on their own, but they were particularly interesting when taken together. The first described the problem (using something once when it’s designed to last hundreds of years) and touched on a few solutions. The second narrowed in on a particular one of those solutions, which Maine passed this year and is starting to implement: Extended Producer Responsibility, or the idea that companies should shoulder some of the burden for the plastic they’re introducing into the system and make moves to reduce it.

Let’s first state the obvious: plastic has transformed the world. It has allowed for medical breakthroughs, for the existence of cell phones and helmets and takeout containers and kayaks and N95 masks and all manner of functional and frivolous things that make our lives safer and easier.

But what makes it so useful (durability, longevity) is also makes it problematic. Plastic takes hundreds of years to degrade, but before it does, it breaks down into tiny shredded pieces that end up in our water and soil and eventually our bodies, not to mention the bodies of all fish and mammals and birds that exist in the wake of our choices.

For decades, the messaging around all of this was that using more plastic, particularly single-use plastic of the water bottle and takeout container variety, wasn’t really a problem as long as you were virtuous and diligent about recycling. That implied that the problem was solvable by consumers, if only we would just do our part and drag our brimming blue bins to the curb or the transfer station each week.

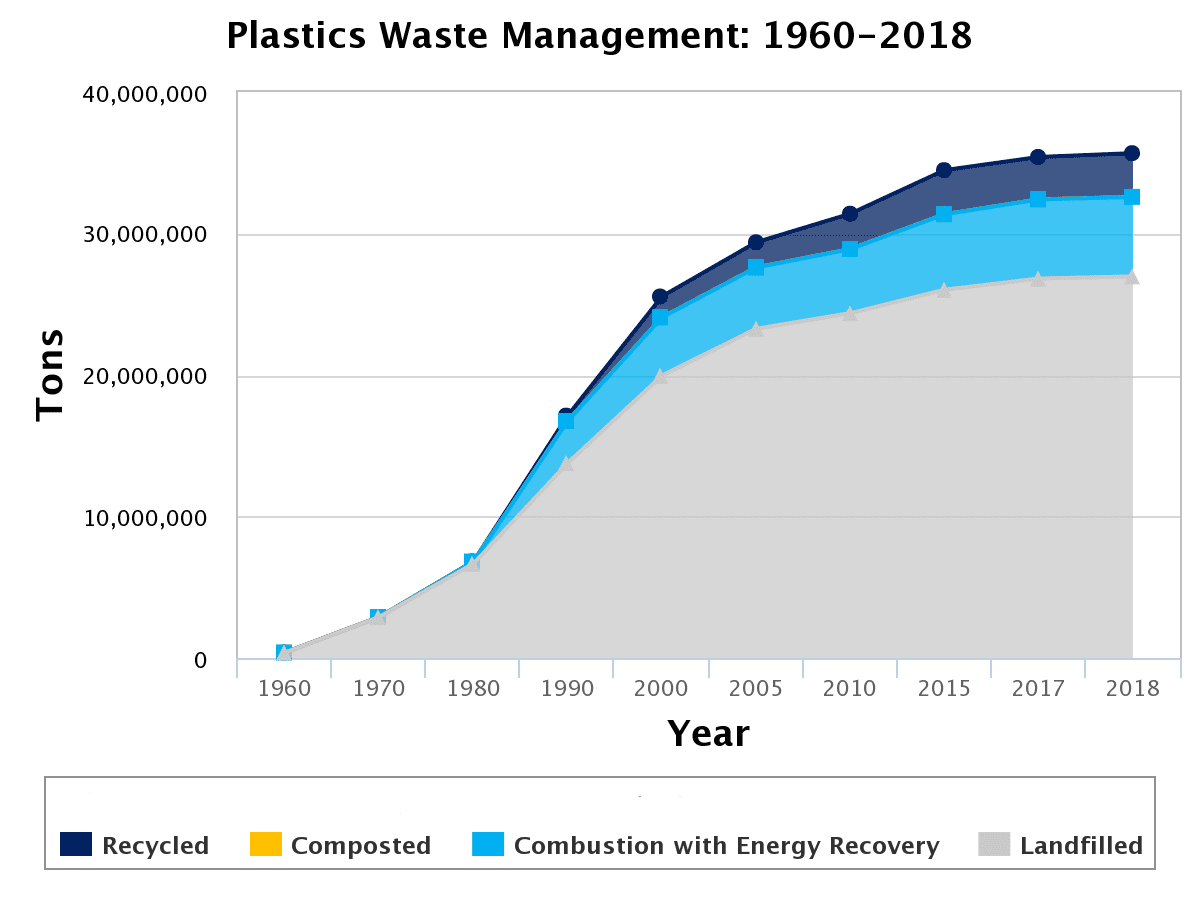

That hasn’t worked as well as we’d hoped. Only 9% of the 35 billion tons of plastic produced worldwide since 1960 has been recycled. Roughly 16% has been combusted for energy, and the vast majority — 76% — has been landfilled.

Recycling plastic isn’t like recycling glass or aluminum, which can be crushed and melted and reformed an infinite number of times without degrading. Plastic, depending on the type, can typically only be melted and reformed once or twice or maybe three times before it becomes too flimsy to be made into anything else.

Recycling is also market-dependent: if it’s too expensive, or there’s no one to sell it to, many waste companies simply won’t accept it. That became painfully obvious in 2018, when China effectively stopped taking much of the plastics we’d been dumping on them for decades. Communities across Maine and elsewhere cut back on recycling programs, and some stopped recycling altogether.

In recent years, legislators and advocates have been attempting to shift some of the responsibility onto the companies designing and making the packaging, particularly as production of single-use plastics has soared. It’s expected to continue to grow another 30% by 2026.

“We’re looking at the next big petroleum peak,” said Jackie Savitz, chief policy officer of Oceana North America, speaking at College of the Atlantic this week. “We’re not going to be using as much petroleum in our cars, so what are they going to use it for? They want to figure out how to sell more, and they’re going to do that through plastics.”

Oceana, a nonprofit ocean conservation organization, is working on shifting the messaging around single-use plastics.

“We’re at a funny moment in American history and also in world history,” said Andrew Sharpless, chief executive officer of Oceana, “where people’s identities as citizens have been diminished, and their identity as a consumer has been elevated. And so people believe, instinctively, that every problem can be solved by a buying choice. And that their choice as an individual consumer is the most morally significant thing they can do.”

Making better choices is all well and good, said Sharpless. “But there’s a higher level identity we each carry around with us, which is our identity as citizens, of, if we’re lucky, a democracy that still makes policy in response to its people… which in this case, means passing laws to force source reduction in the pollution called single use plastic.”

Recent EPR laws passed in Maine, Oregon and California are aimed both at forcing reduction at the source, by incentivizing companies to redesign their packaging, and streamlining and supporting recycling programs with the money coming in. That will be particularly important in rural states like Maine, where recycling programs often flounder for lack of volume and high transport costs.

If the proliferation of single-use plastics were an overflowing bathtub, this approach would be like turning off (or at least down) the faucet and also getting a mop to soak up the water that’s already on the floor. What we’ve been doing for decades, said Savitz, is creating increasingly sophisticated mops while the faucet continues to gush.

Will the recent EPR laws passed by Maine, California and Oregon actually result more readily-recyclable packaging that’s less dependent on single-use plastics? That remains to be seen.

EPR alone may not result in dramatic changes overnight, at least according to the industry representatives on this other packaging webinar, put on by the Product Stewardship Institute in June. Bans or fees on certain products, landfill and incineration penalties, reuse and recycling targets, and public company commitments also drive packaging design change, said Scott Cassel, CEO of the Product Stewardship Institute.

But EPR will be “instrumental in organizing and making recycling really operational” in parts of the world where that infrastructure is lacking, said Gloria Gabbellini, director of environmental policy for PepsiCo.

Eco-modulated fees, in which companies pay more, under EPR programs, for certain types of packaging that is less recyclable or not recyclable at all, can drive design change, said Gabbellini. In markets that have eco-modulated fees, PepsiCo sells 7Up in clear plastic bottles rather than the iconic green ones, said Gabbellini, because transparent plastic is easier to recycle and thus costs the company less.

California’s law, which Savitz called “the best plastics production policy in the United States,” may be the most effective at forcing a redesign of packaging. That’s not only because California is one of the largest economies in the world, but also because the law requires the packaging industry to reduce the amount of plastic it’s using by 25% by 2032.

It will be several years before Maine’s EPR law is in full force. The Department of Environmental Protection has hired one of two people who will be conducting a stakeholder rulemaking process expected to last months. The program is expected to go into effect in 2026. That timeline is a bit longer than some other states, said Sen. Nicole Grohoski (D-Ellsworth), but it’s what works for Maine.

“The structure of the program is in the bill,” said Grohoski. “But there are a lot of details to figure out, things like what is actually readily recyclable in our state, and how often should those definitions change in order to have certainty for the business community?”

Meanwhile, the DEP is beginning to collect data that will be used in setting benchmarks, because the data we have, said Grohoski, is “so bad that we weren’t even sure where to start.”

To read the full edition of this newsletter, see Climate Monitor: Who should be responsible for all this plastic?.

Kate Cough covers climate change and the environment for The Maine Monitor. Reach her by email with ideas for other stories at gro.r1764344417otino1764344417menia1764344417meht@1764344417etak1764344417.