Last Sunday, The Maine Monitor published an investigation about adult guardianships and a new law that requires probate judges to consider a less restrictive alternative called “supported decision-making.”

The Monitor spoke with guardians, judges, disability rights lawyers, national guardianship experts and people with disabilities.

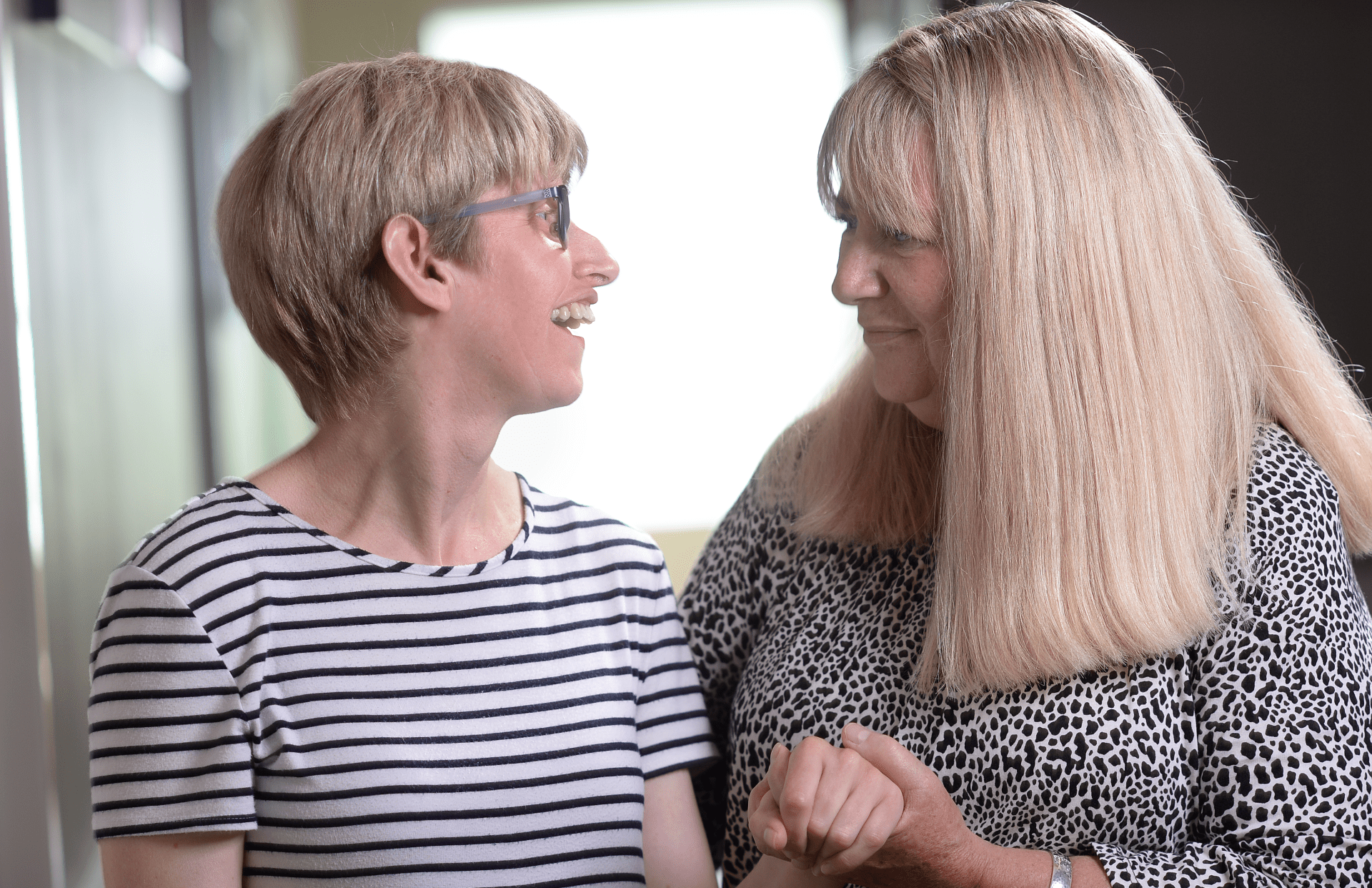

We shared the stories of two women: Kate Riordan, 43, who has cerebral palsy and an intellectual disability, and is “thriving” under guardianship, and Cindy Thielen, 31, who has autism and was able to terminate her mother’s guardianship in 2022.

Here are six takeaways from that story.

“Supported decision-making” is an alternative to guardianship in multiple states, including Maine

“Supported decision-making” is a nationally recognized tool used by people with disabilities to help them assess the consequences of big and small decisions. The person picks supporters and talks through a decision.

About one-third of states have a definition of supported decision-making in state law, according to a 2022 analysis by the American Bar Association.

Maine’s probate judges infrequently opt for supported decision-making

A state law that went into effect in late 2019 requires probate judges to consider supported decision-making before appointing a guardian. Yet, Maine’s judges have infrequently gone for supported decision-making.

Guardians are supposed to be a last resort to make medical, financial and housing decisions for an adult whom a judge deems cannot make or communicate their own choices.

No court or state entity has tracked the probate courts’ use of supported decision-making in Maine.

Guardianship takes away a person’s civil rights

“Guardianship takes away your civil rights. It takes away your civil liberties and formally — not in some abstract way — is the court taking away your rights and giving those rights to someone else to hold on your behalf or exercise on your behalf,” said Zoe Brennan-Krohn, an attorney with the national ACLU Disability Rights Program.

Under guardianship in Maine, adults retain only three privileges — the right to marry, vote and retain a lawyer. Still, probate judges have the discretion to take away the privileges to marry and vote.

Guardianships can be difficult and time-consuming to end

Thielen’s mother was appointed as her guardian in 2011. This meant Thielen could not technically make financial or medical decisions on her own.

Thielen applied to the University of Maine and was halfway to completing her degree when she asked the probate court to end the guardianship. After one hearing, the probate judge suspended the guardianship. But her case was left in limbo for years.

The state’s top disability advocacy organization, Disability Rights Maine, intervened in 2021.

Eleven years after the guardianship was granted, a probate judge gave Thielen control of her life back on April 12, 2022.

Supported decision-making may not work for everyone

Kate Riordan has used sign language since she was in preschool, but because she has cerebral palsy, she lacks the fine motor skills to spell words with her fingers. She fills in the gaps with gestures, spoken words and an iPad filled with icons and programmed responses.

We spent a day with Riordan and watched how with gentle suggestions from her mother Debbie Dionne, Riordan can find answers to questions using her iPad. Riordan knows her mother is her guardian. She doesn’t have the words to say what a guardian does.

A barrier to Dionne and Riordan using supported decision-making is that Riordan does not initiate decision-making. She does not have the language tools to ask for advice, Dionne said. When a decision needs to be made, Dionne starts their discussions.

“Kate is thriving and happy and flourishing,” Dionne said, “because I’m in her life and making sure that happens.”

Stigmatization of guardians could have negative consequences

Opposition to guardianship risks cutting services, policies, money and resources for people who still need them.

It also risks dividing the disability community between the people who need guardians and those who don’t, said Kim Humphrey, whose adult son Dan has autism and requires multiple support people to get through the day.

“If you say that ‘nobody’ needs a guardian and then you meet somebody like him, well then, is he nobody?” Kim said.