COLUMBIA FALLS — Residents of the sleepy hamlet of Columbia Falls are grappling with whether they want to take on oversight of a $1 billion, 2,500-acre Flagpole of Freedom Park proposed by the family behind Wreaths Across America.

The park, with its eight miles of loop roads, six miles of gondolas, several villages, campgrounds, a hotel, theater, restaurants and shops, would be more akin to a small city. The company expects the development, which co-founder Rob Worcester described as “part national monument, art historical adventure, immersive tech-driven museum and architectural wonder,” to attract 6 million visitors and 5,000 employees, most of them year-round.

That’s substantially more than the number of visits logged at nearby Acadia National Park, which broke records at 4 million in 2021, and a workforce roughly the size of the year-round population of Bar Harbor, where many of Acadia’s tourist services are based.

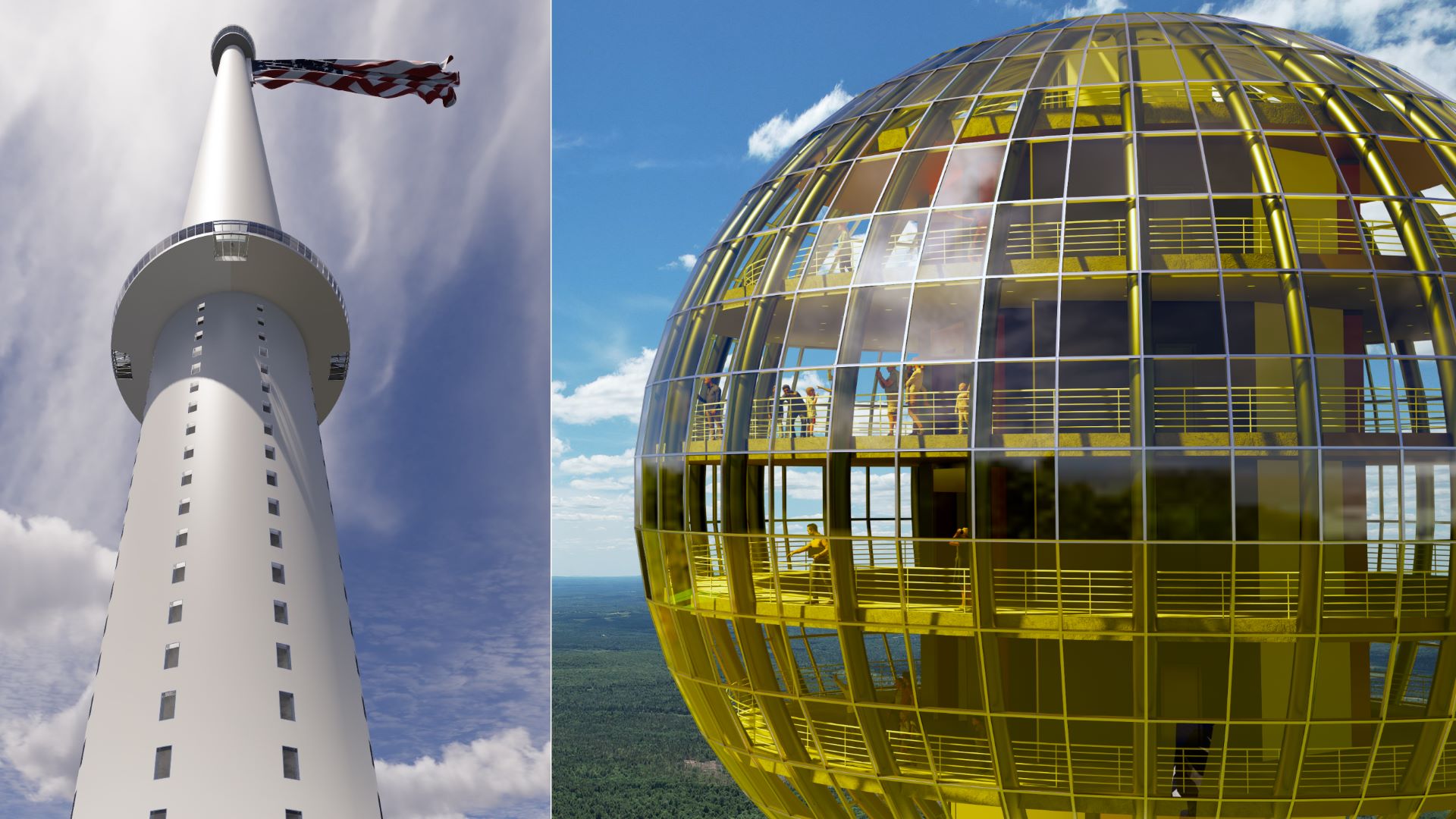

The center of it all would be a flagpole, standing 1,776 feet above sea level, 300 feet taller than the spire of the Empire State Building. Three elevators inside the pole would sweep visitors up to glass observation decks boasting views for 100 miles in every direction.

If residents vote to incorporate the land on which the park is to be built, it would allow the project to avoid time-consuming and more rigorous review by a state planning commission. That strategy would place nearly all of the planning responsibility in the town of Columbia Falls, population 476.

That has some people worried.

“This is not a local or regional level project,” said Dr. Yuseung Kim, chair of Policy, Planning and Management at the University of Southern Maine. “Their plan is a national level project that involves feasibility studies, environmental impact studies, transportation analysis, and economic studies and forecasting … I don’t think local level planning boards or the regional level planning agencies have that capacity or the expertise.”

The Worcesters want to build on land currently under the jurisdiction of the state Land Use Planning Commission, which oversees planning and zoning in the unorganized territories.

Rather than begin the permitting process with the LUPC, the Worcester family is seeking to take the land from the commission’s oversight by incorporating 10,400 acres via annexation into the town of Columbia Falls, where zoning is much less stringent.

If voters approve the annexation, the family will be able to move through the permitting process more quickly, and Columbia Falls would be tasked with overseeing the planning, construction and governing of what amounts to a small city in the woods.

“The purpose of the annexation is to avoid the LUPC,” Columbia Falls Planning Board member Jeff Greene said at a June 1 workshop. Greene was quoting Roger Huber, a Bangor lawyer hired by the town to help it evaluate the proposal.

“If the annexation does not happen, it’s very unlikely that the project could happen,” Greene continued, reading from notes Huber sent him in response to questions from town officials. Although the company would still have to get planning board approval, Greene read, “a vote for the annexation is sort of a vote for the project.”

Annexation is relatively rare in Maine, and requires approval from both the Legislature and voters of the municipality. The Legislature is typically loath to stand in the way of a town’s desires: since 1985, lawmakers have approved all but two of the 14 boundary change bills that have come before them, according to the Maine State Legislature’s Law and Legislative Reference Library.

Lawmakers approved a bill this spring allowing Columbia Falls to incorporate the land as long as voters approve the plans in a referendum, which hasn’t been scheduled.

The Columbia Falls annexation law passed in an emergency session and was signed by Gov. Mills less than a month after it was introduced. This law is unusual in several respects, including that it strips protections designed to ensure a municipality’s ordinances are at least as stringent as what the LUPC has in place.

Maine statute requires that when a municipality incorporates land previously under LUPC jurisdiction, officials in that town must adopt rules that are at least as protective of the “existing natural, recreational or historic resources” as what the commission has on file.

To make sure resources are protected after the transition, commission staff review a town’s land use ordinances and comprehensive plan before handing off regulatory authority. If the municipality’s ordinances are not up to the LUPC’s standards, the commission retains authority until satisfactory regulations are adopted.

The Columbia Falls annexation law does away with those protections by including language stating that the LUPC would have no regulatory authority over land use in the town if the referendum is approved.

“We would not have that kind of role for the Columbia Falls annexation,” Stacie Beyer, executive director of the LUPC, told the committee reviewing the bill this spring. The LUPC did not take a position on the legislation. Beyer told the committee that in its current form, the town’s zoning ordinance would be unlikely to meet the commission’s standards.

The proposal is also unusual because it is being brought forward by a resident, Worcester Wreath Co. founder Morrill Worcester. Other annexation cases reviewed by The Monitor were proposed by municipalities looking to enlarge their boundaries, often to incorporate existing development.

As resident David Perham put it on Wednesday night: “We’ve been given this, whether we wanted it or not.”

If the town rejects annexation, the land will stay within the jurisdiction of the LUPC. The 10-member commission and staff review developments ranging from solar farms to ski resorts, as well as issuing permits for smaller plans, including single-family homes and boat launches.

If Flagpole of Freedom Park remains under LUPC control, it’s not clear it would be allowed without first having the area rezoned. The commission did not respond to a question on rezoning by the Monitor’s deadline.

Rezoning is a lengthy process on its own, and one with no guarantee of success. If one were required, the Worcesters could apply for LUPC permits only after the commission approved the rezoning.

It would also mean the family would likely be forced to wait to apply for permits from other agencies, such as from the Maine Department of Environmental Protection and the Maine Department of Transportation. Those approvals will be necessary regardless of whether the land is annexed.

The permitting process, particularly if the LUPC is involved, would likely take years. That could push back the company’s ambitious timeline of having the first phase of the park (roughly 40%, said Worcester) open by July 4, 2026, to coincide with the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence.

Marianne Moore, the Republican state senator who sponsored the annexation bill, said she did so after being approached by the Worcesters. The family assured her it would still get the necessary permits, including from state agencies. Moore was pleased that Columbia Falls residents would get a say in the process.

“It was going to be harder if they were in the unorganized territory,” said Moore. “If they can do it locally, there still will have to be permitting done but it will be a lot faster.” Incorporating the land into Columbia Falls would also direct any tax revenue to the town, rather than the state or county, Moore added, which she described as “a win-win.”

In testimony this spring, local and regional officials also expressed support for bringing the land into Columbia Falls, saying the town most impacted by the development should have authority over the plans and receive any benefits from the park.

“Adding this taxable land into our town taxable property will benefit the existing taxpayers by lowering the tax requirements for all other property owners,” Columbia Falls Selectman Tony Santiago wrote in testimony. Tax revenues would otherwise flow to the state and county. Park literature boasts that the development will bring in annual associated state tax revenues of $27 million.

Worcester said the family had considered developing the park as a nonprofit, which would have potentially exempted it from property taxes, but the plans proved too complex. The family also did not want to compete “with other organizations that are doing great things for veterans.”

Several proponents of annexation, including the Worcesters and Tim Pease, an attorney representing the company, pointed to the town’s 2019 Comprehensive Plan as evidence that local officials have the capacity to evaluate and enforce regulations around the plans.

“They have an approved comprehensive plan as of 2019,” Pease told the legislative committee considering the bill. “So I think they’re in a good position to have the people to address the land use requirements.”

Comprehensive plans, however, serve more as a foundation and guidance document for adopting a land use ordinance, said Charles Rudelitch, an attorney and executive director of the Sunrise County Economic Council, which supports area businesses. Such plans offer “a chance for a community to think through its values,” but are typically not legally enforceable, said Rudelitch. “The ordinance is really the key.”

Columbia Falls does have a land use ordinance in addition to its comprehensive plan. The land use ordinance, adopted in 1999 and updated in 2018, totals 15 pages. It includes three pages of regulations on building and dimensional requirements, followed by a building permit application.

The ordinance resembles those of other rural towns, giving property owners broad latitude over what to do with their land. Most of the regulations are a single sentence. The document makes no mention of lighting, noise or screening, apart from requiring that mobile home lots “be permanently landscaped.”

By contrast, the land use ordinance in Bar Harbor, home to Acadia National Park and one of the state’s busiest tourist spots, runs nearly 400 pages. A seven-member planning board meets at least monthly to review applications, none of which approach the scale of what the Worcesters are proposing.

Bar Harbor also has a comprehensive plan, a design review board, full-time planning and code enforcement staff, municipal water infrastructure, a sewage treatment plant, a hospital and a paid fire department. Like most rural towns, Columbia Falls has volunteer boards and no comparable infrastructure. It shares many services with nearby towns, an arrangement residents would like to keep.

“I don’t think they have the expertise,” Kim of the University of Southern Maine said of local authorities. It would be difficult, and expensive, to assemble outside consultants to review the plans, he added, and the town would be tasked not only with analysis but with enforcing the regulations.

Washington County Commission Chair Chris Gardner pushed back on the idea that local entities would not be able to evaluate or manage a site of this magnitude, especially given that they could hire outside consultants.

“Any state agency is only filled with people who drive back to their small community. Just because they have a title and an office does not make them any wiser,” said Gardner. “You want the communities themselves actually making these decisions, rather than maybe an overarching state board like the LUPC.”

Proponents of the park also pointed out that at least two state agencies — the Maine Department of Environmental Protection and the Maine Department of Transportation — would be involved at some level, regardless of whether the land is annexed. The Federal Aviation Administration may also have to approve the massive flagpole.

Those processes, they argue, and the planning board hearings in Columbia Falls would give residents across the region a chance to weigh in on the plans.

The project is also large enough that it will likely trigger increased oversight from the DEP in the form of Site Law, which is designed for developments expected to have substantial impact on the environment. Under Site Law, the agency expands its review to include stormwater management, groundwater protection, infrastructure, wildlife, fisheries and noise.

But Site Law covers only issues directly related to the environment, said Kim in an email. It would not evaluate other aspects important to a planning and development, such as “housing, employment, infrastructure, sense of community, scenic beauty, tourism and hospitality industry, commerce, population size, age structure of population, demands for education, traffic demands.”

So far it’s been a frustrating process for some town officials. At the June workshop, officials said they asked the Worcesters for several studies, including surveys and information on the environmental and economic impact of the plans, but the company has yet to comply. Company representatives did not attend the June meeting.

Huber, the Bangor lawyer hired by the town, canceled his appearance at the meeting a day in advance because he had little new information, but told officials he doesn’t think the company is avoiding the town. The Worcesters, he said, are likely trying to get documents in order before June 13, when they are slated to have a preliminary meeting with the DEP.

“He was pretty disappointed, as we were, with the information we’ve received so far,” said Greene, the Planning Board member.

Several residents raised concerns Wednesday night about language in the newly passed law that holds Columbia Falls responsible for all planning costs associated with annexation. Although Morrill Worcester promised to reimburse the town for costs to hire professionals to review the plans, he has yet to sign the document the town sent him. It’s unclear whether the law would preclude the town from forcing the company to pay — nor are there estimates on how much the planning process could cost.

“The first time it was brought up was Feb. 28,” said Greene, “and every time he’s said we’re going to sign the paperwork and he hasn’t done it.”

Town authorities acknowledged that hiring outside consultants would quickly get costly. Greene agreed with a resident who suggested the town bring on a team of lawyers and other experts, given the enormity and complexity of the plans.

Philip Worcester, the chairman and one of the two Worcesters on the five-member Planning Board (one is an alternate), said last week that the land use ordinance also would need revising.

Asked about his last name, Philip Worcester said he is “distantly related” to the wreath company Worcesters and does know them. But, he said, “we don’t have Sunday dinner together.”

It would likely be several months before the town has answers, he added. “Right now we can’t even answer our own questions.”

The idea for Flagpole of Freedom Park began roughly a decade ago, said Worcester, as the company kept acquiring land for growing balsam to make wreaths for its business, Worcester Wreath Co. The company, started by Worcester’s father Morrill Worcester 30 years ago, supplies most of the wreaths to the nonprofit Wreaths Across America. Morrill’s wife Karen has long served as executive director of the nonprofit.

“We have people come here to see the property now where the brush is grown,” the younger Worcester explained, and “we thought, you know what would be great is if we created a destination around just that, a place where people could go and reflect, and do it around the property where we grow the balsam for the wreaths.”

The 2,500-acre development would essentially function as its own municipality. Plans include 1.5 million square feet of building space ringed by eight miles of loop roads, and criss-crossed by six miles of gondola lines that would ferry the park’s 6 million anticipated annual visitors from place to place.

A village in the southwestern corner would feature a 900-foot long main street, 4,000-seat 4D theater, shops, a non-denominational chapel and restaurants, as well as an anchor hotel. There would be dedicated fire and emergency services on the premises.

Hiking trails would meander through blueberry barrens and spruce forests, where hundreds of migrant workers converge each fall to harvest the tips of branches to weave into wreaths, and down to the shores of Peaked Mountain Pond. Nine miles of double-sided walls would display the names of 24 million veterans, separated into 55 areas — one for each U.S. state and territory.

The park would include six “halls of history” dedicated to veterans of the country’s major conflicts — the Revolutionary War, Civil War, World Wars I and II, the Korea and Vietnam wars, and the Kuwait/Iraq/Afghan wars. Each would feature actors in period costume, re-enactments and an immersive ride, which Worcester was quick to stress would be educational rather than designed for thrills. “We want it to be so real that you can feel like you were there. That’s the goal,” said Worcester.

The center would be the flagpole topped by a flag that would spread larger than a football field, woven from carbon fiber and kevlar. It would be visible from certain vantage points in Acadia National Park, said Worcester. That’s roughly 40 miles away.

The elder Worcesters are consistent contributors to Republican candidates, but the family has insisted the park will be an apolitical destination.

“We’re going to do this and be authentic, unfiltered,” said Worcester. “We’re never gonna tell people how to interpret it, you know, so you can come see exactly as close as we can depict what happened.”

The company is designing an area, “The Roots of America,” aimed at honoring the contributions of Native Americans to both the war efforts and the country’s founding.

“We did want to make sure that everybody’s history was included,” said Worcester. He said the company met with an indigenous representative whose father served in the armed forces (“so she sees the value of it”), but has yet to form partnerships with local tribes.

The park would abut land owned by the Passamaquoddy Wild Blueberry Co., which is owned, managed and operated by Passamaquoddy Tribe members. A representative of the company declined to comment on the plans.

The Worcesters also plan to incorporate “the story of slavery and how all that happened,” said Worcester. The family has yet to begin working with groups representing Black Americans, he said, but is eager to do so.

A lot of other unanswered questions remain, particularly around infrastructure, services, and workforce housing. The park would employ roughly 5,000 people, most of them year-round, an arrangement the family hopes will be attractive enough to lure employees to an area that has struggled to find enough staff in the past. Water and sewer treatment operations have yet to be designed.

Columbia Falls does not have a sewage treatment plant, and shares emergency response services with nearby towns. During the comprehensive planning process, residents said they like the shared arrangement and would even be interested in further consolidation.

Housing for employees may prove particularly challenging. The company has not incorporated employee housing into the plans, said Worcester, although it is open to the idea. Campgrounds and cabins on the property could provide temporary spaces for the 8,500 construction workers the family estimates will be necessary throughout the building process, said Worcester.

Worcester Wreaths also owns a dormitory with beds for 700 seasonal employees in nearby Harrington.

It remains to be seen where the 6 million visitors would stay, with few hotels nearby. “We’re not going to immediately have accommodations as far as hotels,” said Worcester, something the company sees as an opportunity for local property owners who want to rent out their properties as short-term rentals.

Those thousands of employees and millions of expected visitors will have a profound impact on the entire region, not just on Washington County, said Kim, the professor from the University of Southern Maine.

“(Employees) will commute, that will increase the commuting traffic, that will increase the housing demand, increase the housing prices and rents. That much demand will have a significant impact … new housing is not just new housing. It means more roads, more sewer lines, more electricity supplies.”

Worcester acknowledged that traffic in Ellsworth in particular would be “extremely busy.” Many visitors will likely arrive via coastal Route 1, a scenic byway that hugs stretches of spectacular coastline and passes the Schoodic section of Acadia National Park, an area that already struggles with heavy summer traffic. The company will encourage drivers to take Route 9, which runs north from Bangor.

There’s also the question of electricity and how much buildout the grid would require to handle the plans. Judy Long, a Versant representative, said the company was aware of the project but hadn’t received any formal requests or determined if it would need an upgrade.

Despite the hurdles, most residents and officials have expressed a desire to attract more-year round residents and families and expand the economy. The median household income in Columbia Falls — $43,194 — lags considerably behind the statewide median. The town’s population shrunk between the 2010 and 2020 census, and its residents are aging.

“We’ve always really dabbled in the tourism-based economy,” said Commissioner Gardner. “This is a chance, I think, to grow that a little further and to grow it in such a way that I think really attaches to a very strong branding that is Washington County.” The Worcesters’ deep roots in the region reassures him they have the region’s best interests at heart.

But the scope of Flagpole of Freedom Park also seems to conflict with comments in the Comprehensive Plan. In that document, residents express “a desire for smaller to medium sized scale, environmentally friendly operations in keeping with the quiet rural nature of Columbia Falls.”

Gardner acknowledged those tensions, and said they can be summed up with a saying he often hears about Downeast. “The only two things we hate are change and the way things are.”

The origins of the Worcester Wreath Co. date to 1971, when the company began selling wreaths and supplies. Founder Morrill Worcester began laying the garlands on veterans’ graves in 1992 after finding himself with surplus, which he gathered up and drove to Arlington National Cemetery. The tradition eventually led to the founding of Wreaths Across America, bringing the family wealth and national recognition.

The family has “some” veterans on his mother’s side, said Worcester, and his sister is married to a marine, but mostly the family’s reverence for those who have served “is just because we have what we have because of what they did. I’m a chicken. I don’t want to deal with guns and all this stuff. And they did that for everybody.”

Wreaths Across America was incorporated as a nonprofit in 2007 and began its explosive growth not long after that. The nonprofit, which charges $15 per wreath “sponsorship,” more than tripled its revenue in the past five years, from $8.3 million in 2015 to $26.1 million in 2020.

Today, between Morrill Worcester, Worcester Holdings and Worcester Wreath, the company and family owns more than $10.2 million in property across Columbia Falls, Harrington and the unorganized territory, according to The Ellsworth American, not including $848,500 worth of Columbia Falls property owned by Wreaths Across America, which is tax-exempt.

The organization has come under scrutiny for its close relationship to Worcester Wreath Co., which supplies the bulk of the wreaths placed on service members’ graves. In 2018, according to the Portland Press Herald, Wreaths Across America paid $10.3 million — 70 percent of its revenue — to Worcester Wreath Co.

The arrangement is not illegal but is unusual, and has prompted criticism from watchdog groups. Charity Navigator, which evaluates nonprofits on a variety of accountability metrics, gave the group a “failing” grade.

The company has dismissed the criticism, saying its relationship with Worcester Wreath Co. was never a secret. It also added a section to its website explaining the relationship.

Flagpole of Freedom Park would operate as a separate, for-profit venture. The family has used some of the money from its wreath-making business to help get it started, said Worcester, but he reiterated that taxpayer funding will not be sought or used for the project.

Money to build the park would come primarily in the form of founding memberships ranging in cost from $660 to $1,800 (the company expects to need roughly 250,000 of them) as well as corporate sponsorships.

“Our sponsors and things would be advertisers instead of donors — they can write that off,” said Worcester. Once the park is up and running, revenue would come from ticket sales to certain attractions, such as the flagpole observation decks, merchandise, food sales and attractions. Entrance to the park would be free. The company plans to donate some proceeds from the park to charity, said Worcester.

Local officials are proceeding cautiously, assuring residents that a vote will not be scheduled on the annexation until they have all necessary information.

“The primary goal, in my opinion, of these two boards is to acquire as much information — environmental, economic, you name it — and get it to you so that you can make a fully informed decision,” Selectman Nancy Bagley told residents. If this goes through, she said, “there is going to be a social impact.”

Commissioner Gardner said those wondering “how (the Worcesters) can possibly pull this off” would have to wait for answers.

“It’s monumental, literally and figuratively,” said Gardner. But “if they want to try to run this race, and use private money to do it, and attract investment to our county — who are we to stop them?”

Kate Cough is the energy and environmental reporter for The Maine Monitor. She can be reached by email at gro.r1762034322otino1762034322menia1762034322meht@1762034322etak1762034322.

Editor’s Note: A previous version of this story inaccurately described grid capacity near Columbia Falls.