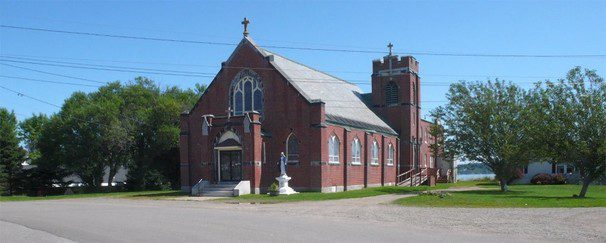

The Friends of St. Ann’s are hoping for a miracle to save the historic brick church at Sipayik, which is scheduled to be demolished in the coming weeks.

Armed with a new and much lower estimate on the cost to at least replace the brick work, Hilda Soctomah Lewis of the Friends of St. Ann’s says, “We’re hoping that public sentiment” for the church can sway decision-makers to stop the demolition and that funds can be raised to restore the structure.

Tribal members at Sipayik have not been allowed the opportunity to decide on the fate of the building that sits on a point overlooking Passamaquoddy Bay at the center of the community.

Lewis, who has been involved with efforts to repair the church since 2005, said, “I feel this church is special, but it’s not about me. It’s about the people of our tribe and the need to have a center where we can gather — not just our elders but our youth, too.” While it has served as a Catholic church, Lewis is hoping it can become a nondemoninational center for worship.

Others are supportive of the effort, with Chris Altvater among those wanting to see the church restored. “It means a lot, especially to the older generations,” he said. Pat Phillips, former Chief Rick Doyle’s widow, would like to see a spiritual center with a garden that could be used by people of all faiths to come together for healing circles, wakes, funerals, ceremonies and celebrations of life.

Dwayne Tomah, a tribal language keeper, noted that the Catholic church is a sensitive issue at Sipayik. “It’s a mixed blessing for a lot of tribal members,” he said. “Traditional people are glad it’s being torn down, but others support the church and don’t want to see it demolished.”

“We want to come together as a community,” he added.

“The only way to stop it now is with a big commitment of funding,” said Adam Newell, who has been helping with the removal of the bell and furnishings from the church. He noted it would cost less than $1 million to repair the existing building, while a new wooden structure might cost at least $1.6 million.

Plans for the demolition, though, are proceeding, and on March 31 the church bell was rung for perhaps the last time, drawing a number of people to hear it before it was removed. The 19 stained glass windows had previously been taken out for safe keeping, and the statue of Mary and the pews have also been removed for storage. The windows are considered to be of museum quality, and the workmanship throughout the church is exceptional.

The Catholic church at Sipayik has been closed for a number of years because of concerns about its condition and mold issues, with Mass currently celebrated on the reservation at the former cultural building that was used by the Beatrice Rafferty School and is next to St. Ann’s Church.

Some tribal members also attend Mass at St. Joseph’s Church in Eastport, but Lewis said, “We have elders who feel more comfortable being at church on our reservation.”

Lewis noted the last time the church was opened was for the funeral of her son David Moses Bridges, a tribal culture-bearer, when family and close friends were allowed to go in during the funeral Mass.

Lewis observed that most churches hold fundraisers for repair or restoration work, but the Friends weren’t “allowed to do one.” In 2016 she did send a proposal to the Portland Diocese for the restoration of the building. The proposal calls for restoring the chapel, partially demolishing the convent section but reusing part of that structure to provide a space for community gatherings, a kitchen, dining area and offices.

An oversight board would make decisions regarding the building, and Lewis says the diocese would not have to carry the costs for the church. She was told, though, it could not then be a Catholic church. She says her proposal would be for a nondenominational worship space.

In 2019, Lewis and others from the parish met with Bishop Robert Deeley of the Portland Diocese to discuss proposals. The diocese did not respond to a request from The Quoddy Tides for more information on its plans.

However, notes of the meeting that Bishop Deeley forwarded afterward state that Lewis said that the Friends of St. Ann’s would raise money to repair the church. While the land that the church is on belongs to the tribe, the diocese and the tribe have not been able to identify who actually owns the building.

The diocese, though, has custodial responsibility for a church that is going to be used for Catholic worship, the notes state. It was agreed at the meeting that cost estimates for restoration would be obtained and that the diocese and the Friends of St. Ann’s would conduct a feasibility study on raising the necessary funds.

In March 2022 the tribal council, though, voted to allow the Portland Diocese to tear down the church and also decided not to hold a referendum at Sipayik on the issue.

However, nearly a year later, on February 28, 2023, the council voted to authorize a referendum on whether to have the diocese demolish the church or have the church restored, with costs borne by a board set up by the Friends of St. Ann’s.

But at a March 29 administrative meeting with tribal councilors, which was not a formal council meeting, a consensus was reached, following a presentation by tribal attorney Craig Francis, to not hold the referendum and to allow the demolition to proceed. Francis relayed that, if the planned demolition was delayed, the diocese indicated that the tribe would be responsible for the demolition costs, according to Lewis, who was at the meeting.

Lewis says that she does not want the tribe to be responsible for the church or its demolition but rather that the Friends would take on the responsibility for restoration. She also had wanted the entire tribal population to decide on the matter and not just the tribal council.

Estimates on the cost to restore the church vary. In February, the masonry firm of Richmond & Thaxter of Cherryfield, which recently completed masonry work at the Peavey Memorial Library and is working on the Tides Institute’s Masonic building in Eastport, gave an estimate of $680,000 to remove and replace the exterior bricks on the church and bell tower.

A 2013 report funded by the National Park Service had found that the structure was in relatively good condition and recommended repairing the building, with a cost estimate of over $1 million. Then a 2019 assessment conducted for the diocese had estimated the cost for renovating the church at $4 million and for restoring it at $4.43 million.

A fact sheet accompanying the proposed referendum that was not held in 2022 stated that renovation costs would be $7 million to $10 million.

Pride and joy of community

When the church was built in 1928 to replace the former wooden church that was destroyed by a fire it became the pride and joy of the community, according to historical accounts, and Lewis has written that tribal members feel a deep connection to the building.

“Community members have been baptized, received communion, confirmation, have been married, have seen their children and grandchildren receive the same and have passed through this church on their final funeral service,” she wrote in a proposal to restore the building.

She noted that the tradition of the tribe is to hold a wake for its members in the household of the family, with people coming and going, day and night. Sometimes family homes are too small, and the church and attached former convent section would allow tribal members to hold traditional wakes in a suitable environment.

“We need to have a spiritual center on the reservation,” Lewis stated. “The vibrant spirit our community once had has deteriorated. There are rampant drugs, there is no respect for elders and no respect for one another.”

The church holds many memories for Lewis. During Christmas “the church would be just so bright. We had a creche next to the altar. When you walked into that church and with the smell of the fir and the pine, it was just so beautiful.” Other celebrations were also held throughout the year, such as during May with the placing of a crown of flowers on the statue of Mary.

Whether such celebrations can be held in a church at Sipayik in the future, though, remains to be seen.

Sign up here to receive The Maine Monitor’s free, periodic newsletter, Downeast Monitor, that focuses on Washington County news. This article is republished by The Maine Monitor with permission from the Quoddy Tides.