Jennifer Gunderman’s hands moved quickly from bean to bean, snipping the long vegetable right at the top and dropping it into her five-gallon bucket.

The former organic farmer turned University of New England public health professor made the short drive from Belfast to Swanville in early August, joining more than 15 other volunteers who wore wide brim hats to ward off the bright sun as they harvested yellow beans from the Maine Coastal Regional Reentry Center fields.

In a normal year, inmates serving their last few months of incarceration work the fields as part of their rehabilitation before rejoining society. But in this most unusual of years, when the pandemic cleared out jail cells and fewer people got arrested as most of society came to a near standstill, there weren’t enough inmates at the center to keep up with the work of picking each crop at its peak.

“The Reentry Center has done amazing things,” Gunderman said as she squatted in the field. “How can we let all this food go to waste?”

That food comes from about 18 acres planted with more than 15 different vegetables, from beets to onions, potatoes to corn, butternut squash to turnips, said Capt. Robert Walker, detention manager at the Waldo County Sheriff’s Department. From those fields, the food goes to more than two dozen food pantries, soup kitchens and other places where people in need can easily pick up something healthy to put on the dinner table.

The Swanville volunteers are among many people across Maine who have offered their time and talents to help Mainers in need weather the first six months of the global pandemic.

Walker said in a normal year, the center can accommodate 32 residents – he prefers to call them residents rather than inmates – but because of coronavirus restrictions, he can take only 16. In early August, he had fewer than nine and expected to need more volunteers for another few rounds of harvesting. But by the end of September, 11 residents were at the center, and Warren said were able to keep up with the harvest on their own.

Another volunteer bean-picker, Dale Rowley, said his day job as director of the Waldo County Emergency Management Agency taught him a thing or two about coping in a pandemic. He listed off four things typically lacking: food, water, shelter and fuel.

“If we can build up capacity here to feed people, we don’t have to wait for the federal government to save us,” he said.

Picking across from him, Lisa Kushner of Belfast said she ventured out early that Saturday morning because since her retirement from counseling, she’s looked for a sense of purpose. Not far down the row, Eliot Van Peski of Swanville, a farmer who specializes in grass-fed beef and lamb, talked about how lucky he was to be able to volunteer.

“I’m self-employed, I work outside, I’m not in the company of many people,” he said, ticking off reasons he’s been able to cope during the pandemic.

And in less than 36 minutes, Van Peski had already filled his bucket – emblazoned on one side with an advertisement for Viking Lumber & Building Supply, and an American flag on the other – and went looking for a box for the beans.

Walker estimates that the gardens will yield 200,000 pounds of vegetables this year. That will be even more than last year, helping to bridge the gap for more people who need more help because of the pandemic.

For the inmates who are able to help with the harvest this year, the signs on the grounds of the garden – such as Self-Change Street and No Risk Road — reinforce what they’ve learned as part of their rehabilitation. Walker said picking food for someone else creates a community connection for the residents who may have never felt part of something bigger than themselves.

“It’s important to give and expect nothing in return,” he said.

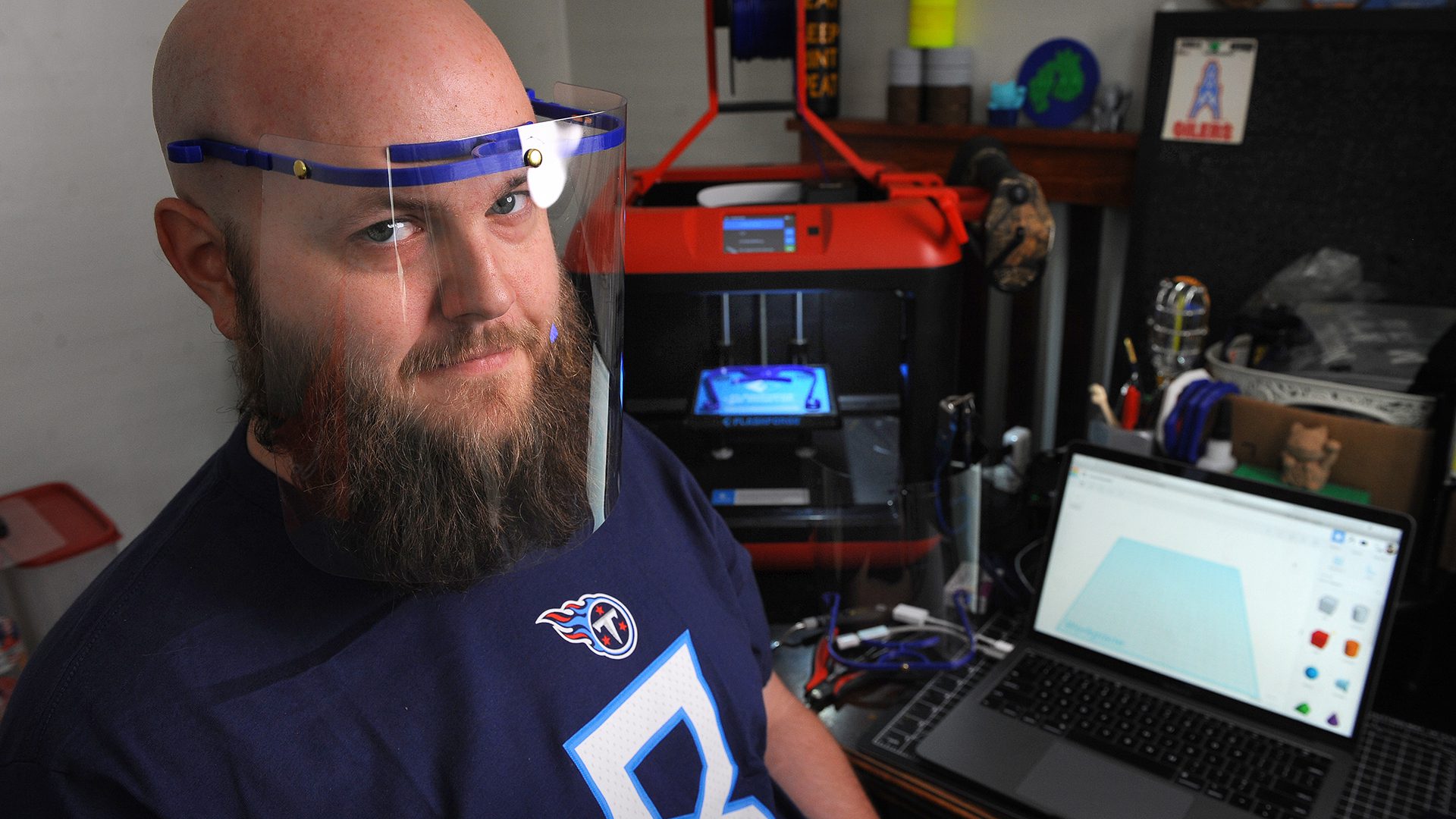

A grassroots effort to make PPE

When the virus first hit Maine and the dire need for personal protective equipment became a national crisis, Silas Coffin and others stepped up to help.

As president of the Kennebec Valley Community College 3D Print Club, he knew the members could pitch in.

“As a club we knew we could print the frame of a face shield, no problem,” he said. “It quickly turned into a community project.”

To coordinate efforts statewide, a group called Grassroots Pandemic Volunteering was formed. Funded by the Perloff Family Foundation, the Maine Space Grant Consortium, the KVCC Student Senate and numerous individuals, the group has produced more than 8,700 face shields, according to its website.

Many of them went to nursing homes and other small healthcare facilities that needed immediate help, said Stephen LaRochelle, director of library services at KVCC. Overall, the effort included more than 170 volunteers, 147 3D printers and 51 printing hubs across the state.

When the college shut down in response to the pandemic, the school was on break. Many students had checked out 3D printers to take for school assignments, so LaRochelle emailed the students to see who would be willing to produce the face shields.

“They were all very enthusiastic,” he said. “Before you know it, we were cranking them out.”

LaRochelle said families worked together at kitchen tables to produce the shields, which are often used in healthcare settings to give doctors, nurses and aides a second layer of protection from the disease. For children suddenly out of school, it became a way to feel involved in something important, he said.

“You always feel helpless as a kid, especially in this situation,” he said. “I think it was therapeutic for kids to participate.”

After the initial wave of requests from nursing homes and rehabilitation centers, LaRochelle said public libraries, people working at polling stations and schools started asking for the face shields as well.

Filling the online learning gap

Ryan Kelley, an Old Town High junior, is good at fixing computers, so when it came time to complete his Eagle Scout project, he knew it would be something computer-related. And when the pandemic made it clear that students would need to continue to learn from home at least part of the time, he set out to make sure no one missed school because they didn’t have the right equipment.

“I do have a lot of experience with building PCs,” said the 16-year-old. “I knew with COVID there was a lot of online learning needs.”

Kelley has been collecting old laptops and updating them to serve the needs of his school district.

As part of a collaboration with Regional School Union 34, Kelley installs Google’s operating system on the computers so they can function like Chromebooks. He wants to ensure that all students in the district that covers Alton, Bradley and Old Town have what they need, and even after he meets the requirements for the Eagle Scout project, he’ll continue if others need the help.

“If we have enough old computers, I will focus on other nonprofits and schools,” he said.

A community survey conducted this summer by RSU 34 showed more than 50% of families had some difficulty securing reliable devices for remote learning and 17% have inadequate internet access, according to an August story in the Bangor Daily News.

At a Sept. 7 event, community members dropped off old computers to Kelley and 14 other volunteers who checked the machines to see if they were working, recycled those that could not be repaired and loaded software into the ones that could be used, said Christopher Kelley, Ryan’s dad and Scoutmaster. The district needs 270 computers and Ryan has collected about 100.

“As his Scoutmaster, and his father especially, I am very proud of his creativity and thoughtfulness, and effort to work on a service project that meets such a huge need,” Christopher Kelley said via email, noting that the troop has five Eagle Scout projects in progress. “I am equally excited and proud of those scouts and their effort to help others, but also I am excited to see how scouting teaches so much about character development and what it means to be a good citizen.”

Ryan, who juggles school, his Eagle Scout project and a job at McDonald’s, said he’s traveled as far as Portland to pick up old laptops. Anyone who would like to donate can contact Troop 76 on Facebook or through Kelley’s GoFundMe page.

Picking up groceries, fixing lawn mowers

Navy veteran Jordan Simpson needed something to do when the pandemic first hit in Maine. With his job on hold and college courses moving online, he had too much time on his hands.

“I found myself listless,” he said. “It was not great for my mental health.”

Many of the stories of what folks are dealing with are absolutely heartbreaking and many are beyond our ability to do much to help, but we do what we can.”

— Mike Tipping, Maine Peoples Alliance

He’s not quite sure how or where he became aware of Mainers Together, an effort launched in March by the Maine Peoples Alliance. But he was more than glad to volunteer to pick up groceries for the elderly or those with compromised immune systems. Months later, he’s still picking up groceries for two elderly people who are not comfortable going to the store.

“I go pick up whatever they need, prescriptions or over-the-counter medicine,” said Simpson, a husband and father of three. “One of the ladies had me help by fixing her lawn mower. Whatever I can do to make sure they don’t need to be doing too much in public.”

Simpson is one of about 1,000 volunteers who have signed up through the Mainers Together website representing every county in the state, according to Mike Tipping, communications director for the Maine People’s Alliance. The group initially spent $25,000 on direct aid, including 850 grocery cards, and has been accepting donations to keep things going, he said.

They’ve received more than 1,500 requests for help.

“Many of the stories of what folks are dealing with are absolutely heartbreaking and many are beyond our ability to do much to help, but we do what we can,” Tipping said.

Moving forward, he said the group will push the state and federal governments to address the needs laid bare by the coronavirus and economic downturn.

An ‘eye-opening’ need for food

Back in March, Main Street Grocery in Damariscotta started making and delivering meals to people in need in Lincoln County. They couldn’t keep up and started asking around for help. That’s when the Lincoln County Food Initiative — a collaboration among more than 50 nonprofits, businesses and individuals – formed to step in, said Jessica Breithaupt, the project coordinator.

At first they planned only to continue and expand the meal delivery service, she said. Before long the services grew to include a hotline, a volunteer network of 60 people, weekly food drives and emergency food box delivery.

The group now delivers meals prepared at Camp Kieve in Nobleboro – which did not have campers on site for the first time in 95 years because of the pandemic – to people in nine Lincoln County towns, two times a week. Volunteer drivers log 300 miles a week and have delivered meals for 25 weeks, she said.

“The need appears to be consistent,” she said. “People needing assistance don’t fit into the perfect social service box.”

Helping to fill that need are volunteers like Marge Greenleaf and Suzanne Strachan. Both filled their vehicles with boxes of prepared meals on a humid late August morning outside the dining hall at Camp Kieve.

“It’s a great way of giving back,” said Greenleaf, the events coordinator at Wavus Camp in Jefferson. “I have one lady who hasn’t left her house since we started.”

Strachan, president of Cheney Insurance in Damariscotta, spends two mornings a week delivering meals along her 41-mile route.

“It’s fantastic,” she said, noting that one recipient gives her candy to show his appreciation. “I can’t tell you how rewarding it is. People are just really thankful.”

Those receiving help include families who typically need food for two months before they are able to get back on their feet, Breithaupt said. Others are elderly or those recovering from illness and are particularly vulnerable to the virus. Breithaupt said the coronavirus didn’t so much create the need as uncover it.

Before the virus, “we would drive by houses and not really understand,” she said.

In addition to regular meals, the group has delivered 33 boxes of emergency food to those who call the hotline because they don’t have anything in the refrigerator.

“It’s been eye-opening,” she said.

‘Sewing warriors’

When Tufts University medical student Katie Ward’s clinical – the supervised patient interaction portion of her education – got suspended in March because of the virus, she started thinking about ways to help. She called more than 60 healthcare facilities across the state to see if they had enough personal protective equipment.

They did not. So on April 2 she started a Facebook page called Making Cloth Masks for Maine, which eventually grew to 340 members. Using money from a GoFundMe site and the generosity of her parents, Ward and about 60 other sewers got to work.

Some volunteers cranked out 100 masks each week. Ward, who is studying to be a general surgeon, said she’s not that fast, but enjoys using her hands to make something tangible. Her group donated masks to nursing homes and assisted living facilities across the state, for staff and residents. From St. John Valley Health Center in Van Buren to the Children’s Advocacy Center of York County – and a whole lot of places in between – the group donated at least 4,270 masks.

Ward, who had never organized a big volunteer effort, said she was surprised at the response to the Facebook page and all they accomplished. But on second thought, she realized it’s the way Mainers typically help each other.

“Human nature’s amazing that way,” she said. “People see a problem and everyone wants to chip in to fix it.”

Once the demand for cloth masks started to drop and many of the volunteers – herself included – went back to school and work, Ward put the group on pause.

“Because the future of this pandemic is unpredictable, I’ll keep the group active on Facebook in case the demand returns and we need our sewing warriors to ramp up mask production again!,” she wrote in a July 12 post.

Addressing mental health struggles

When the pandemic hit, Betsy Rose, the volunteer president of the Bangor chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness Maine, thought there was nothing she could do. She felt strongly that the support groups she leads need to be in person. She often reads body language and wanted to be able to follow up with someone who might be so overwhelmed they would walk out of the room.

That lasted about a week. With the help of guidelines from the national office, she honed her Zoom skills and again began leading support groups for people with mental illness and their family members.

“It’s been a really interesting experience and at first was kind of awkward,” she said. “But not for long.”

From our perspective, COVID is not just a physical health pandemic; it’s a mental health pandemic as well.”

— Jenna Mehnert, National Alliance on Mental Illness Maine

She let the 400-500 people on her email list know that the groups were being offered online at the same time they were previously held in person. And unlike pre-pandemic groups, these sessions drew people from all over the state to the same meeting.

While she’s helping families understand they are not alone, nor the first to go through the trauma of trying to help a loved one with mental illness, the pandemic has brought to bear another difficulty.

“Not being able to visit someone in the hospital has been a huge problem for some of my families,” she said.

A recent report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that in late June, 40% of U.S. adults reported struggling with mental health or substance use, one gauge of the pandemic’s impact.

“I think from our perspective, COVID is not just a physical health pandemic; it’s a mental health pandemic as well,” said Jenna Mehnert, executive director of NAMI Maine.

That’s where Rose and dozens of other volunteers trained by NAMI come in.

Mehnert said part of the challenge is the things we’re supposed to do to protect ourselves from COVID-19 – isolate, stay home instead of travel, stay away from crowds – are the things that are particularly difficult for people with mental health challenges. One of the major factors that leads to suicide is social isolation, which is especially true for adolescents, she said.

The isolation is further complicated by the uncertainty of when life might get back to normal and the fact that adolescent brains are not fully developed.

“We don’t know when this is going to end,” she said. “Life is just completely discombobulated. It’s challenging for everybody but much more challenging for 13- to 25-year-olds.”

Mehnert is also keeping an eye out for middle-aged Mainers, particularly men who might be significantly impacted by an economic downturn. She wants to make sure they are able to get the help they need.

“Mental health is very personalized,” she said. “There is not one approach.”

Rose said although she was initially reluctant to move support groups online, and anticipates getting back to in-person sessions as soon as it is safe, she does see a future that continues to use Zoom as well.

“I really want to, at least at some level, have a support group online,” she said. “Throughout the winter, what could be better?”