For nearly 15 years, Paul Weiss fortified hospitals and healthcare facilities in southern Maine for outbreaks of infectious disease with thousands of pieces of medical equipment. But by the end of 2018, Weiss’ job had been replaced by a private, out-of-state business and supplies critical to Maine’s capacity to respond to an outbreak were going in the trash.

Unable to bring himself to throw them out, Weiss stashed medical masks, protective equipment, discontinued respirators and satellite phones in a storage unit off Route 100 in Falmouth.

Maine had invested millions of federal dollars in protective medical equipment and emergency ventilators specifically to prepare its hospitals for infectious disease, bioterrorism and mass casualty events through the federal Hospital Preparedness Program. Yet, years of spending cuts during former Gov. Paul LePage’s two terms in office and the federal budget sequestration left Maine’s three regional resource centers in Portland, Bangor and Lewiston strapped for cash to replace aging and expiring medical supplies.

As funding for the southern Maine region dropped to less than 10 percent of what it was in the early 2000s, Weiss said he was “constantly scrounging” to buy replacement medical supplies. By 2018, his work was reduced to a small office at Maine Medical Center in Portland and his nonprofit — where he was now the sole employee — was unable to pay the $10,000 deposit to bid for the state’s new hospital preparedness contract.

The LePage administration instead selected All Clear Emergency Management Group in Raleigh, North Carolina to take over the 18-month contract starting on January 1, 2019. Weiss worked through December 2018. At the end of the month, he handed over the keys to the Falmouth storage unit to the Maine CDC and walked away.

Fifteen months later, a woman in her 50s arrived at the Portland International Jetport from Italy with a cold.

Pandemic hits Maine

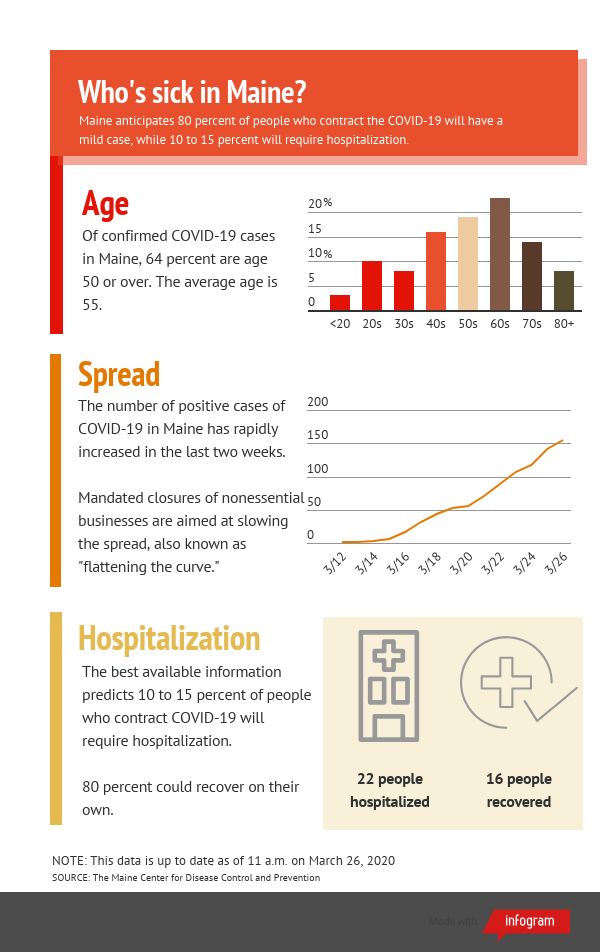

Except, it wasn’t a cold. Gov. Janet Mills announced on March 12 that the woman was the state’s first presumptive positive case of COVID-19, a respiratory illness caused by the new coronavirus that originated in Wuhan, China in late 2019 and rapidly spread across the globe.

The coronavirus spreads person-to-person during periods of close contact when the respiratory droplets of an infected person’s cough or sneeze is inhaled or touches another person’s mouth or nose, according to the CDC. Surfaces contaminated with respiratory droplets can also transmit the virus to a new person.

A shortage of protective equipment for healthcare workers in Maine was an immediate concern as 55 additional people tested positive for COVID-19 within a week. The state began distributing gloves, face shields, masks, gowns and shoe covers to hospitals, and Mills requested the federal government send 300 additional ventilators to Maine from the Strategic National Stockpile, which would more than double the state’s existing capacity.

As the number of positive tests surpassed 100 that weekend, the head of the Maine CDC Dr. Nirav Shah said the state was working to distribute even more protective equipment in a “fair and equitable manner” amid state and national shortages.

Yet, this was the exact equipment that Weiss told the state and hospitals to buy during the 15 years prior. According to Weiss, much of it expired and was thrown away without being replaced.

“All of this really expensive equipment that was critically important for infectious disease outbreak, the majority of it expired. There was no maintenance done on it, and literally things were tossed in the garbage,” Weiss said.

With grant money from the federal Hospital Preparedness Program, Maine’s regional resource centers had purchased thousands of surgical and N95 masks, beds to increase hospital capacity during a patient surge, window-mounted air purifiers and supplies to turn hospital rooms into isolation rooms. Emails reviewed by the Maine Monitor confirm that Weiss told hospital administrators and Maine CDC employees that equipment was expiring and needed to be replaced, but that it was being thrown away.

Robert Long, the communications director for the Maine CDC, said Wednesday that every viable piece of personal protective equipment that Weiss returned was refurbished, reordered or reused. The supplies were reallocated to healthcare facilities in the southern Maine region or provided to an organization that sends supplies to developing countries, he added. The storage unit Weiss left was also cleared and usable items were sent to hospitals, Long said.

Maine’s regional resource centers did not leave a stockpile of protective equipment that could have been used against COVID-19, according to Long.

The Maine CDC has used its own stockpile and the federal Strategic National Stockpile to distribute personal protective equipment to healthcare providers and first responders during the last two weeks. Half of the distributed supplies came from Maine CDC’s stockpile, Shah said.

The last supplies from the Public Health Emergency Preparedness team stockpile were distributed this week and are now gone, Long said. Maine officials were also told the state may not receive more supplies from the federal Strategic National Stockpile, Shah said on Thursday.

Prior to the arrival of the coronavirus, the emergency ventilators Weiss purchased were also removed from the state’s inventory because, “they were unserviceable and were the wrong types according to hospital respiratory therapists,” Long said.

Nationally, there is a critical shortage of ventilators with only 16,600 ventilators in the national stockpile, the Center for Public Integrity in Washington, D.C. reported this week. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration rolled back restrictions on ventilator modifications and manufacturing to increase the capacity of U.S. hospitals to support patients in respiratory failure during the national public health emergency.

The Maine CDC disputed responsibility for the current shortage of emergency medical supplies during a joint press conference with Gov. Mills on Tuesday, saying these were decisions made two years ago while LePage was in office.

“Right now our focus within Maine CDC and (the Maine Emergency Management Agency) is getting the stocks and supplies and protective equipment that we have out to first responders and healthcare providers in the field,” Shah said.

Exposure risk grows

Maine has received two shipments from the Strategic National Stockpile to replenish supplies of protective equipment but it needs more, Shah said.

Some of the medical supplies from the Strategic National Stockpile are past their expiration dates, and recipients were instructed by the U.S. CDC to do “integrity checks” of the equipment, Shah said on Thursday.

The state distributed more than 22,000 pieces of protective medical equipment on Monday to local fire, law enforcement, regional hospitals, tribal communities, state facilities and emergency service medical service providers. An additional 16,000 pieces of protective supplies were shipped out on Tuesday.

That’s a drop in the bucket to what first responders will need in the coming weeks, said Rick Petrie, the regional EMS director for 12 of the 16 counties in Maine. Petrie is also the executive director of the Atlantic Partners EMS, which bid on the healthcare preparedness contract put out by the LePage administration in 2018.

Ambulance crews are coming in contact with patients experiencing coronavirus symptoms — such as fever or trouble breathing — before they are tested. Emergency medical services responded to over 100,000 calls to 911 in Maine last year, Petrie said, with respiratory calls making up a notable portion. All those calls now need to be handled with a “higher index of suspicion,” he said.

Maine EMS and regional directors are developing protocols to screen patients who have coronavirus symptoms and for ambulance services to transport coronavirus patients safely. Calls to 911 had not increased as of Tuesday and inter-hospital transfers and emergency room census were down, Petrie said.

“I think we are really, truly in that proverbial calm before the storm,” Petrie said.

He predicted Maine would see an increase in presumptive coronavirus calls to 911 and inter-hospital transfers of positive coronavirus patients with a surge of new cases emerging in coming weeks. If the supply of protective gowns, masks and gloves runs out during the surge of sick people, then EMS personnel will still respond but may have to be quarantined for 14 days and stress ambulance services that are already understaffed.

Maine is not unique. Shortages of emergency responders and money to purchase protective equipment ahead of an outbreak are national problems, and hospitals have not been able to fill the gap, Weiss said.

“The expectation that hospitals will pick up the slack in funding and personnel is completely unrealistic and it’s played out — there’s no question about that — this is what has happened across the country,” Weiss said.

“In Maine, most of our fire departments are volunteer, EMS is primarily volunteer. We have a very minimal level of professionals here that are paid full-time and our emergency preparedness depends upon those people. If you not only require them to be volunteers, then you don’t fund them on top of that and then you don’t fund programs: we are way, way unprepared for this. We are so unprepared it’s scary,” he said.

The Maine CDC confirmed 155 cases of COVID-19 in 11 of the 16 Maine counties on Thursday, though there is a substantial backlog of tests that have not yet been confirmed or denied by laboratories in Maine. Shah warned that the disease was likely already in every county and that cases would continue to climb.

The agency also announced on Thursday that it had confirmed community spread of the coronavirus in Cumberland and York counties.

United Ambulance Service in Lewiston and Auburn has already transported two patients with confirmed positives for COVID-19, said Joe LaHood, operations manager for the station. It had also responded to at least 10 calls to 911 for patients experiencing symptoms of the coronavirus.

The ambulance service is short staffed with 70 EMTs, advanced EMTs and paramedics of a possible 100.

At Naples Fire and Rescue in Cumberland County — where the highest concentration of positive coronavirus cases has emerged — the ambulance service is in short supply of protective gowns, said Lucien Gendron, the EMS Coordinator for the station.

“We do have some, but we don’t have enough if there is a decent outbreak in the area. That’s a little concerning,” Gendron said.

Gendron requested more gowns from the state and was told the station could be moved to the top of the list if the situation changes. On Wednesday, Shah announced that the state had begun asking healthcare institutions to report daily stocks of personal protective equipment on top of data already collected on available intensive care unit beds and ventilators.

“It’s difficult to know where you should be going, unless you know where you are,” Shah said. “And in situations like this, those timely data helps us know where we are so we can make decisions on where to go.”

The Maine Monitor reached out to 20 local hospitals requesting information about the emergency equipment they have, how well trained the staff is to operate that equipment and how emergency preparedness has changed as leadership transferred from the state’s regional resource centers to All Clear Emergency Management Group. Most representatives said they could not fulfill the requests because the hospitals were too busy handling other communications needs related to the coronavirus. Others acknowledged the requests but did not respond by press time.

New contract stress-tested

Weiss is used to helping to coordinate the healthcare response in Maine as he did during H1N1 and swine flu outbreaks or when the state was preparing for the potential spread of Ebola. The emergence of the coronavirus in Maine during March 2020 comes amid very different circumstances.

The Maine Department of Health and Human Services signed an 18-month agreement on Dec. 28, 2018 with the All Clear Emergency Management Group of Raleigh, North Carolina for $684,222 to analyze its health system’s current capacity, train member healthcare organizations and run surge tests.

Ginny Schwartzer, chief executive officer of All Clear Emergency Management Group, said by email that the group had four full-time coordinators working in Maine and had fulfilled all its state and federal contract deliverables and project timelines.

The Maine Monitor asked Mills if she stood by LePage’s decision to outsource Maine’s federal Hospital Preparedness Program to an out-of-state company. Mills said, “I’m sorry, I can’t answer the question about the contract.”

Mills was Attorney General when the LePage administration outsourced the contract to an out-of-state company. The Portland Press Herald reported during the transition of the two administrations in November 2018 that Mills planned to review the contract once in office. It ultimately wasn’t changed.

While it was difficult to lose his job because of the switch to All Clear Emergency Management, Weiss said his bigger reason for speaking out was frustration with the government’s short memory on the value of preparedness.

“Now we’re in a situation where we’re going to be paying for it dearly, because they’re just scrambling to try to catch up. You can’t scramble and ever catch up. It’s preparedness,” Weiss said. “If you’re prepared at the beginning — even if you’re less prepared, you’re still prepared — and they’re just completely unprepared now. It’s a nightmare situation.”

Shah said Thursday that the mandated nonessential business closures and physical distancing people in Maine are now living under seemed unfathomable just a short while ago.

“The things that we thought were utterly inconceivable a month ago, now seem blindingly obvious,” Shah said.

When pressed on what the All Clear Emergency Management Group was doing during the current outbreak, Mills said, “The rest of your question is really addressed to MEMA, who is responsible for inventorying all of our available equipment, and I believe they have done that. I’m pretty confident they’ve been doing that in close coordination with Maine CDC and with the federal government with FEMA.”

MEMA does not have its own stock of medical supplies and instead works with the Maine CDC, which would have conducted the inventory, said Susan Faloon, a spokeswoman for the state agency. MEMA is a coordinating agency and assists in getting supplies to providers or in working with FEMA to secure additional supplies, she said.

Long confirmed the Public Health Emergency Preparedness team completed an initiative in February to locate all the state’s existing mass casualty incident trailers. Weiss previously inventoried the trailers stationed in southern Maine.

Schwartzer said All Clear Emergency Management Group is overseeing the Healthcare Coalitions of Maine, which are supporting the response of the Maine CDC, while the state agency, in conjunction with MEMA, coordinates resource allocation, distribution of inventory and mobilization of alternate care sites.

Petrie said Maine was in a neutral position — neither worse nor better off — to handle the coronavirus outbreak under its new agreement with the All Clear Emergency Management Group than if the three regional resource centers were still in operation.

“There are so many priorities out there and it’s a matter of establishing where your money is going to be better spent in order to address a need,” Petrie said. “There was a bunch of federal money out there to get this started and then the problem is down the road, everybody’s scrapping trying to figure out where are we going to get the money to do this?”

Maine Monitor Managing Editor Meg Robbins contributed to this report.