Editor’s Note: The following story first appeared in The Maine Monitor’s free environmental newsletter, Climate Monitor, that is delivered to inboxes for free every Friday morning. Sign up for the free newsletter to get more important environmental news from reporter Kate Cough by registering here.

Maine no longer has any power plants that burn coal as a primary fuel. But that doesn’t mean the June ruling by the Supreme Court in West Virginia v. EPA won’t impact us.

“Maine is the tailpipe of the nation,” said Jeff Thaler, an attorney with Preti Flaherty who has decades of experience in environmental law and policy. “We’re the furthest northeast. To the extent there are more carbon emissions generated in the west or other coal states blown here by the prevailing winds that impacts our air quality and our public health.”

But it does not appear the ruling, which deals with federal regulations under the EPA, will impact Maine’s ability to meet its emissions reductions targets, which include slashing emissions by 45% by 2030 and being carbon neutral by 2045. (Although as I wrote about this spring, some experts have questioned the state’s methods for counting how much carbon our forests are sequestering, an important consideration in meeting our carbon neutral goals.)

The case before the Court was an unusual one because it dealt with a rule that never actually went into effect. In 2015, after trying and failing to pass legislation, then-President Obama signed an executive order establishing the Clean Power Plan, which, relying on a rarely-used section of the Clean Air Act, allowed the Environmental Protection Agency to establish goals for each state to limit emissions from existing power plants.

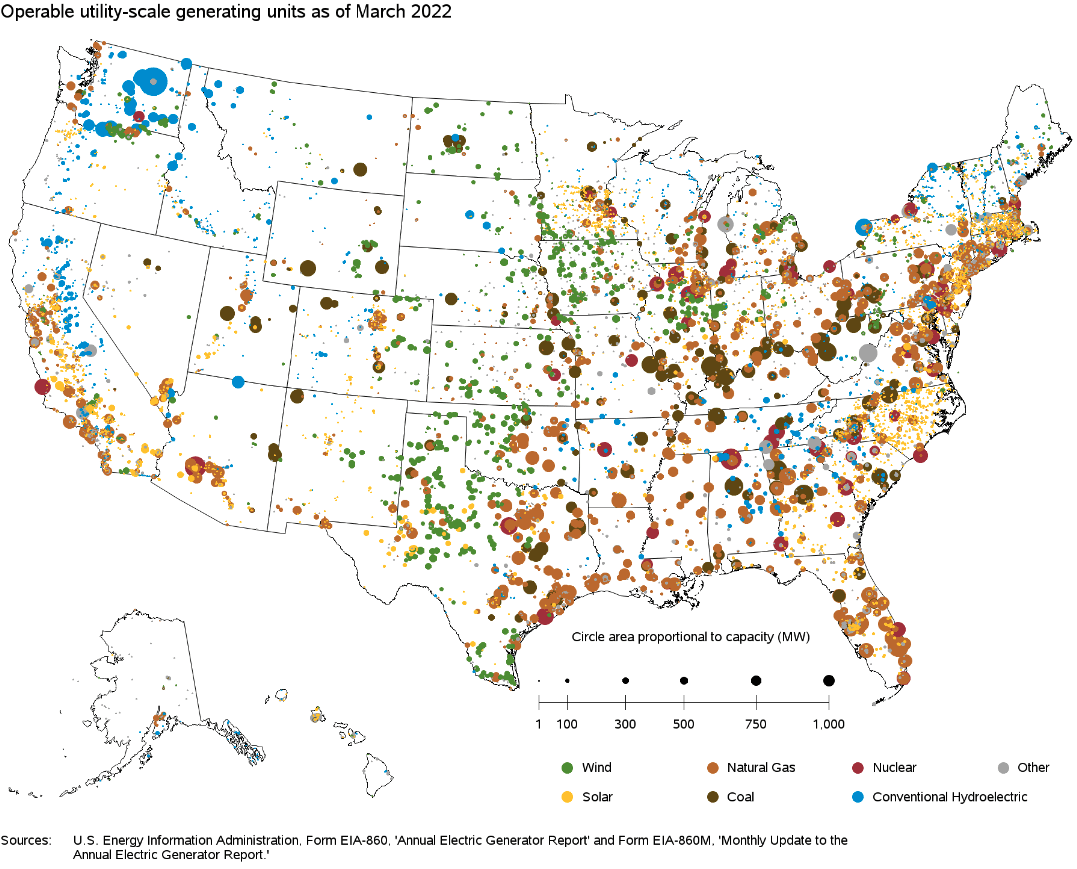

States could choose how they wanted to meet those goals — they could build new wind or solar farms, or switch coal-fired plants to natural gas, or enter into cap-and-trade agreements. The rules were ultimately aimed at shutting down coal and gas-fired power plants and curbing the 25% of U.S. emissions that come from the electricity sector. But they did not sit well with many coal-producing states, who worried about substantial economic and job losses.

Shortly after the final rule was adopted, attorneys general from twenty states, led by West Virginia and joined by several coal companies, sued, claiming the new rules stretched the authority of the EPA. The Supreme Court put the plan on pause in 2016 and the Trump administration repealed it shortly thereafter, replacing it with the Affordable Clean Energy rule, which allowed states to set standards and gave power plants flexibility in complying with them.

Last year, the D.C. Circuit court vacated both the Trump Administration’s rule and the Clean Power Plan. President Biden did not reinstate the Clean Power Plan, but his administration has been working on regulations of its own.

The Supreme Court decision reverses the D.C. Circuit court’s ruling, curtailing the EPA’s authority over the energy sector. The agency can still regulate emissions at individual power plants, but it won’t be able to implement more ambitious measures like cap-and-trade programs without the approval of Congress.

“This kind of decision could go all the way to risking EPA’s ability to set greenhouse gas emissions standards at all,” said Jack Shapiro, Climate & Clean Energy Director at the Natural Resources Council of Maine, in an interview on Wednesday afternoon before the decision came down.

With the passage of the Clean Air Act, signed into law by President Richard Nixon in 1970, Congress granted the EPA expansive authority to regulate the nation’s air quality and determine the “best system of emission reduction” from power plants. Much of the language in the act was intentionally broad, so as to give the EPA room to deal with problems and pollutants that might arise in the future but weren’t yet known.

But Chief Justice John Roberts, writing for the majority, said that by relying on Section 7411 of the Clean Air Act, the EPA sought to exercise “unprecedented power over American industry.”

The Court, Roberts wrote, doubts that Congress intended to delegate such politically and economically significant decisions — “i.e., how much coal-based generation there should be over the coming decades, to any administrative agency,” even though, he said, transitioning away from coal-fired electricity plants may be a “sensible ‘solution to the crisis of the day’.” If Congress wants to give the EPA the authority to do that, it must so say explicitly, Roberts wrote.

Justices Elena Kagan, Stephen Breyer and Sonia Sotomayor dissented, with Kagan suggesting that Congress did indeed intend to give the EPA such broad authority.

“Why wouldn’t Congress instruct EPA to select ‘the best system of emission reduction,’ rather than try to choose that system itself?” Kagan wrote. “Congress knows that systems of emission reduction lie not in its own but in EPA’s ‘unique expertise.'”

“The stakes here are high,” Kagan continued. “Yet the Court today prevents congressionally authorized agency action to curb power plants’ carbon dioxide emissions. The Court appoints itself — instead of Congress or the expert agency — the decision maker on climate policy. I cannot think of many things more frightening.”

Thaler, the Preti Flaherty attorney, said he’d been barraged with calls and emails since the decision came down by colleagues and clients wondering what it signaled both for the U.S.’s ability to meet its climate goals and the court going forward.

“Increasingly it seems like the court in many instances is demanding more explicit and very detailed findings and instructions by Congress before the agencies are allowed to — in the court’s view — properly act and regulate,” said Thaler. “That’s a challenge for Congress because they don’t always have that expertise.”

“Nobody is quite sure of the exact impact whether this is really terrible from a climate change management perspective or not as bad as it could have been,” he added. “People are still parsing it.” It does mean, said Thaler, that any rules made by the EPA going forward will likely be challenged in court.

Gov. Janet Mills and other Maine leaders condemned the Court’s decision, but Jeffrey Crawford, director of the state Department of Environmental Protection’s air quality bureau, told the Portland Press Herald that the ruling will not impact the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative or renewable portfolio standards.

Although it’s unlikely the ruling will impact Maine’s ability to meet its emissions-reduction goals, the message it sends is not a hopeful one, said Thaler.

“It doesn’t send a good signal to the world overall in terms of our ability and approach to reduce carbon emissions as quickly as we need to.”

To read the full edition of this newsletter, see Climate Monitor: Will the West Virginia versus EPA ruling keep Maine from meeting its climate goals?.

Kate Cough covers climate change and the environment for The Maine Monitor. Reach her by email with ideas for other stories at gro.r1751684823otino1751684823menia1751684823meht@1751684823etak1751684823.