This story was originally published by the Machias Valley News Observer.

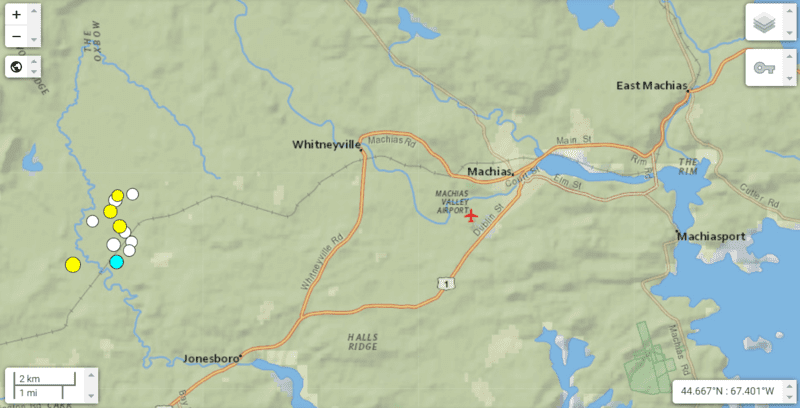

As many as 12 small earthquakes have been reported in central Washington County in the past several weeks, constituting a “swarm,” according to Maine Geological Survey’s Henry Berry.

Local lore says the earthquakes are caused by a fault line running under Centerville, but that’s only partially true, says Berry.

“There are some parts of the world that have active faults that have been identified, where earthquakes are occurring [regularly],” said Berry, citing places like Alaska, Japan, and California. “That’s not the case in the state of Maine.”

Instead of one long fault line located under Centerville, like California’s San Andreas Fault, Washington County’s recent earthquakes are caused by rocks breaking randomly inside the earth’s crust. Each break is technically a fault.

Scientists know that Maine doesn’t have an active fault line, thanks to the work of several seismologists who came to study Maine earthquakes.

“The seismologists came when we first got a decent array of seismometers in about 1975 to study where [Maine’s earthquakes] are and see if we could relate them to any of the mapped faults,” said Berry. “They were disappointed, and they mostly went back to California, where they’re all from.”

“That doesn’t mean we don’t have earthquakes. It just means we can’t see a correlation between the active earthquakes we have now and the old faults we have on the map,” said Berry. (See the state’s list of Maine earthquakes here.)

The Washington County tremors are not dangerous, ranging in magnitude from 1.1 to 3.0 on the Richter scale, but they could teach seismologists something about how earthquakes form. The ability to detect earthquakes with magnitudes as small as 1.1 is relatively recent, said Berry.

“This is a new kind of data that we haven’t had before because they’re so small, and if we get so many of them in one small place, there’s an opportunity for the seismologists to analyze those and get a better idea of the process generating these little swarms.”

Anyone who senses or hears an earthquake can help seismologists by reporting it to the U.S. Geological Survey through their online form found here. Sometimes, people can detect earthquakes so small that they’re hidden within the seismology data. A report can help scientists find them.

“If they know what time it was, they can locate the weak signal in the data,” said Berry. “The seismographs are picking up even more than we know about. Citizen science is a helpful way for people to be involved in this.”

An earthquake swarm also took place in Milo earlier this year, and another was detected in Searsport two years ago.